A sermon on Luke 3:7-18 by Nathan Nettleton

The title of my sermon tonight is “Could Hannah Gadsby be the Messiah?”, and it is not as facetious as you might first think.

For those of you who haven’t discovered her, Hannah Gadsby is a comedian who originally hails from north west Tasmania. Her fame went international this year with the success of her Netflix show, Nanette, which was a searing expose of the way stand-up comedy typically trades on the victimising of minority groups. Her growing fame spiked again just over a week ago when, in an eight minute speech to a breakfast session of The Hollywood Reporter’s Women in Entertainment gala, she said “I find good men talking about bad men incredibly irritating”, and then went on to explain exactly why.

It made headlines. It was very powerful. It was hard to listen to as a man. And it was one of the most brilliantly insightful analyses of the human predicament that you will ever hear in eight minutes.

You can watch it in full here, and I recommend that you do.

Sometimes when I am bowled over by something in the news like that, I find myself wanting to try to manufacture a connection to that Sunday’s bible readings so that I can preach about it. This time though, when I looked at today’s gospel reading, the connections were so obvious that I’m still struggling to know which of two or even three possible sermons I should preach from those connections. And if this sermon ends up being a bit of a mess, it will probably be because I tried to squash them all into one. Unfortunately, I’m no chance of nailing it in just eight minutes either.

John the baptiser, in even less than eight minutes, said to the crowds who came out to be baptised by him, “You brood of vipers! Who warned you to flee from the wrath to come? Bear fruits worthy of repentance. Do not begin to say to yourselves, ‘We have Abraham as our ancestor, we are the good people’; for I tell you, God is able from these stones to raise up any number of ‘good’ people.”

Hannah Gadsby said (and I’m paraphrasing and extrapolating rather than quoting here), Do not begin to say to yourself, ‘I am a good man. Here is the line. There are all the bad men. I am a good man.’ Do not begin to say that to yourself, because God knows that you move the line to suit yourself, and so does everyone else, so there is no limit to the number of men who sincerely believe that they are the good men.

Both John and Hannah are exposing the way that we go about constructing our notions of goodness. Hannah Gadsby explained this quite clearly, and after first making all the men squirm, she went on to say that women had no reason to exempt themselves from this critique and that you could replace the word ‘man’ with white person, or straight person, or able-bodied person, or any number of other categories and everything she had said would still apply.

She said,

Everybody believes they are fundamentally good and we all need to believe we are fundamentally good because believing you are fundamentally good is part of the human condition. But if you have to believe someone else is bad in order to believe you are good, you are drawing a very dangerous line. In many ways these lines in the sand we all draw are stories we tell to ourselves so we can still believe we are good people.

John was saying the same thing. Don’t think there is a clear line in the sand between the children of Abraham and everyone else, or between Christians and everyone else, and that you’re okay if you are on the right side of your chosen line. This construction of goodness, of God’s favour, is just a story we tell ourselves, and when we need to define other people as bad in order that we can believe we are good, we are drawing a very dangerous line.

And the crowds asked John, “What then should we do?”

“Produce fruits worthy of repentance,” he said, and then he went into detail with specific examples for some of those who were among the askers.

I think Hannah Gadsby is saying something very similar here, although she doesn’t address the what-shall-we-do question quite as directly, and by attempting to speak for her here I am in very grave danger of making the exact same mistake that she is exposing. But she’s not here to speak for herself, so I’m going to risk it.

When she speaks about “good men monologuing about misogyny” and about it being “only good men who get to draw that line” in the sand, and that “women should be in control of that line, no question”, I don’t think she’s saying that men shouldn’t ever talk about these things. I think that what she’s saying is that we men, even the ‘good men’, are so used to being in control of the conversation that we are blind to the fact that even when we are talking about women’s experience of male behaviours, we talk over the top of the women and keep the conversation under our control on our terms.

In this context, in this moment of history, “bear fruits worthy of repentance” means “shut up and listen.” Listen and learn. Stop virtue signalling, and listen and learn.

It’s not that men shouldn’t be involved in conversations about the line. It’s that the line they should be talking about is a line based on women’s experience and is therefore defined by women, so it is never a conversation driven by men or dominated by men. Men do not get to define the line.

The tendency to get this wrong is not just a man thing. As Hannah Gadsby said, the same dynamic happens over other divides, and women can be seen doing the same thing when they are on the privileged side.

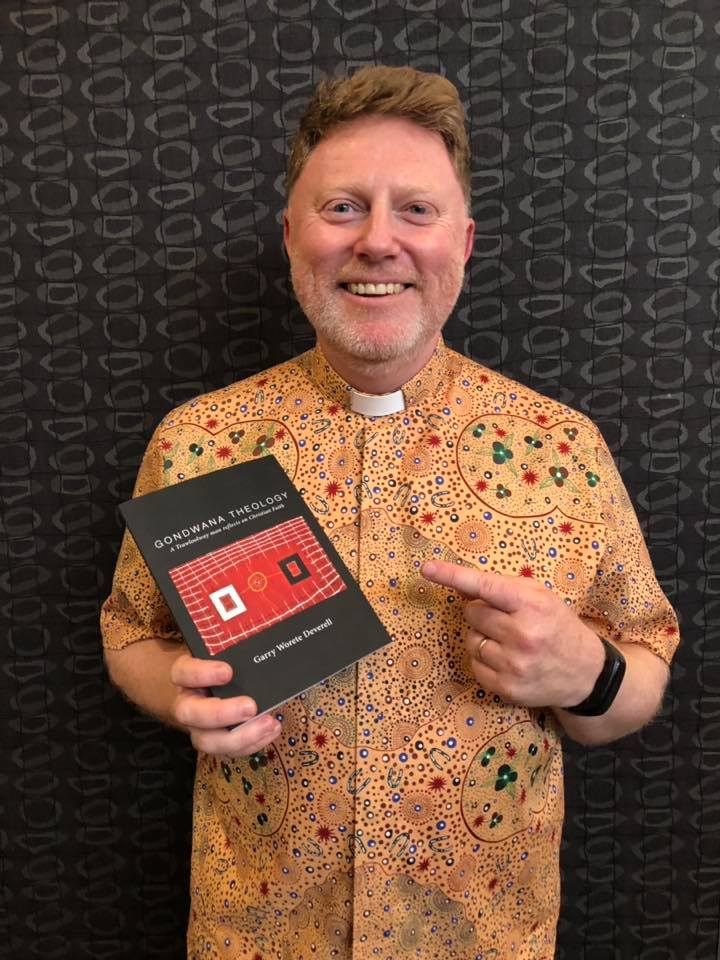

I heard Garry Deverell (an indigenous Tasmanian and former pastor of our church) say a very similar thing at his book launch a week or so earlier. He said that the trouble with most of the conversations between white Australian Christians and indigenous people is that the white-fellas are so busy talking at the black-fellas about their own experience of Aborigines or what their churches are trying to do for Aborigines that they never stop and listen to anything the Aboriginal people have to say.

“Bear fruits worthy of repentance.” Shut up and listen. Stop virtue signalling, and listen and learn.

I immediately recognised myself when he said that. As I did when I heard Hannah Gadsby’s speech. Both were uncomfortable for me to hear, but angry prophets always are. They shine bright search lights into parts of our hearts and lives that we don’t want to see.

But there is another interesting thing that happens with angry prophets. This is my third potential sermon, which I’m hoping I can make work as just a third point of a single sermon.

Angry prophets like John the Baptiser and Hannah Gadsby, and Garry Deverell and Alison Sampson, always divide opinions. They make us uncomfortable, and there will always be plenty of people who get angry about that and criticise and condemn them. John got his head cut off.

But there are others who respond with adulation and awe. Luke tells us that after John’s sub-eight minute sermon, “the people were filled with expectation, and all were questioning in their hearts concerning John, whether he might be the Messiah.” And the papers are reporting that after Hannah Gadsby’s eight minutes, there are people suddenly calling for her to given the job of hosting the Oscars. It’s like they are suddenly asking whether she too could be the messiah.

Sometimes both reactions happen in the same person. We are told that King Herod, after he locked John up, was simultaneously infuriated by him and so fascinated by him that he would bring him out to listen to him again and again. Divided opinions in the one person.

I think that this awe reaction, where we start wondering if this one could be our messiah, happens particularly strongly when the angry prophet preaches a message that is unusually clear and insightful, a message that rips the top off some festering sore and makes it all understandable in a way that is simultaneously frighteningly new and blindingly obvious once it has been said. We recognise the truth of it immediately, or at least as soon as we get over the roaring to life of our defence instincts, and we wonder how we had never seen it so clearly before. And thus the prophet seems extraordinary, messianic even, because they can open our eyes and reveal the truth with seemingly so little effort. Could Hannah Gadsby be the messiah? Or even the Oscars’ host. Which is bigger?!

John was in no doubt that he was not the messiah. I’m sure the same is true of Hannah Gadsby. John is quite clear that his job is to preach a clear path ready for the arrival of another. John was expecting a powerful messiah who would baptise with Holy Spirit and fire, gathering the chosen ones and sending the damned to unquenchable fire. We know that John was missing the mark with some of those expectations, because we read later in the gospel that Jesus is so different from what John expected that he starts to doubt whether Jesus is really the anointed one after all. But if I tried to unpack that any further tonight, that really would be another sermon and I have preached it before (here and here).

Here’s the thing though. We are all yearning for something, for a world made new, for a world that lives up to the call to universal love and respect and reconciliation and care. A world where women don’t need to live in fear, where the wisdom of the first peoples is listened to with care and hope, a world where the hungry are fed and where homelessness is ancient history. Often our yearnings are vague and undefined until some angry prophet puts them into words and we suddenly recognise exactly what we are aching for.

Sometimes the angry prophets are shunned and rejected by nearly everyone, and they seem to be just voices crying out in an empty wilderness with no one to hear. But sometimes something different happens. Sometimes their words strike a deep chord, and suddenly everyone sits up and takes notice. Suddenly everyone flocks out to the Jordan to hear the crazy wilderness guy. Suddenly everyone tweets their calls for Hannah Gadsby to host the Oscars. Suddenly listening to the prophet is the in thing. And I think that’s a Holy Spirit thing.

Usually the prophet doesn’t get to usher in the new day. The prophet is the one who bulldozes the tottering towers of our delusions to clear the way for the new. But when there is a sudden shift in mood and we start welcoming their devastating message, I think it’s a Holy Spirit thing. I think that tells us that something is shifting, that a tipping point has been reached, that we are on the cusp of something new. We stand on tiptoes and crane our necks towards the horizon, because a new day is coming.

That’s what we are doing in this Advent season. John has given us a glimpse. Hannah Gadsby has given us a glimpse. Garry and Alison give us a glimpse. The new day is coming. Come, Lord Jesus, come!

Footnote: A Sydney Anglican priest, the Rev Michael Jensen, last week also published comments on Hannah Gadsby’s speech under the headline The gospel according to Hannah Gadsby falls short. The headline, probably written by an editor, may have made him sound more critical than he intended to be. He describes her as a great preacher, but ends up by saying that after diagnosing our problem, she doesn’t go on to the offer of a new beginning. That’s true, but if he intended it as a criticism (and I’m not sure that he did), I think that would be to misunderstood the role of the angry prophet.

2 Comments

This is an awesome sermon! Thankyou! On reading the title though I can’t help but hear “She’s not the Messiah, she’s just a very naughty boy!”

Ducks guts, Nath!!

Well done!