A sermon on Luke 3:1-6 & Malachi 3:1-4 by Nathan Nettleton

“Prepare the way of the Lord!” What is that all about? How does one prepare the way of the Lord? If someone asks you are you prepared for Christmas, you know straight away what they are likely to mean; “how’s the shopping going?!” Tomorrow night Margie and I are hosting an end of year dinner for the handful of people who still live in the college after the study year ends, and we know exactly what it means to prepare for that.

People in bushfire prone areas have been talking for months about what it means to be prepared, and as the fires rage this past week, they have been finding out whether or not their preparations have been enough. Our reading from the prophet Malachi warned us that the coming of the Lord would be like a refining fire, raging through and burning up all the debris in its path. But what does it mean for us to prepare? How do we get ourselves ready for the coming of the Lord?

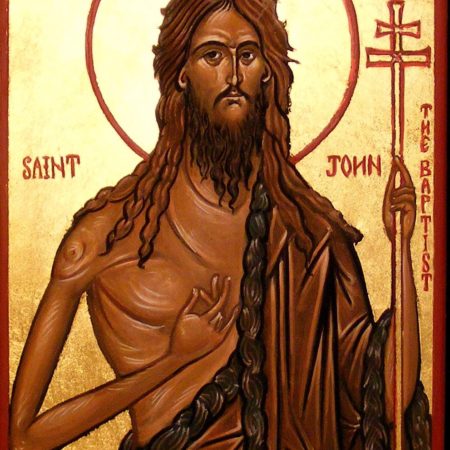

By way of helping people to prepare, John the baptiser calls everyone to “a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins.” But most of us here have already been baptised, so what are we to do now? Surely that doesn’t mean that our preparations are already complete. I bet the people in the path of the fires wish they could just sort out their preparations once and never have to worry about it again!

Luke the gospel writer seems to be suggesting that there are political implications to preparing the way for the Lord. A lot of Christians want to deny this and make out that repentance, faith and discipleship are purely private internal matters, but look at what Luke says here. “In the fifteenth year of the reign of Emperor Tiberius, when Pontius Pilate was governor of Judea, and Herod was ruler of Galilee, and his brother Philip ruler of the region of Ituraea and Trachonitis, and Lysanias ruler of Abilene, during the high priesthood of Annas and Caiaphas, the word of God came to John son of Zechariah in the wilderness.”

It is commonly said that this list of names is there for the purpose of locating the events exactly in history so as to ensure that we don’t think of it as a story with no real context. But the context it is pointing to is not just about the dates, it is political. If it had been just dates, it could have been even more accurate by saying that on the 9th December in the year 30, the word of God came to John. So why does it say more? Well, let me change the names and let’s see if it gives you a feel for how it would have sounded at the time:

In the fifteenth week of the prime ministership of Scott Morrison, when Donald Trump was President of the USA, and Theresa May was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and Daniel Andrews was Premier of Victoria, during the pontificate of Francis I, and while Keith Jobberns was director of Australian Baptist Ministries and Daniel Bullock was the leader of the Baptist Union of Victoria, the word of God came to Bill Bloggs in the bush, and he went everywhere announcing that it was time for people to wake up to themselves, turn things around, and get things back on track.

Do you see what I mean? I didn’t change anything about the sequence of ideas there. But as soon as the names evoke real life associations for us, we see that locating John’s message in the midst of it is making a direct challenge to the status quo. Now that doesn’t mean that preparing the way of the Lord means trying to bring down the government. Neither John nor Jesus seemed particularly intent on doing that. But it does say some important things about our expectations and our mindset as we work out what it means to prepare the way of the Lord.

One of the things it tells us is that we can probably give up any hope that the political processes might actually get things right enough to play a real part in preparing the way of the Lord. Giving up hope in politicians comes fairly easily to us at the moment, but it is still fairly common for Christians to think that we might be able to legislate our way to the kingdom of God.

One of the things which that Luke’s list tells us is that the rulers of this world think they have got the power all sewn up. Every centimetre of territory is accounted for. Some one is in charge in every place. Politically and religiously, the powers are identified and named. But does God speak to the designated powers when the time comes to do something new? No! The word of God came to John in the wilderness.

The wilderness is mentioned twice in the passage, and I don’t think it is simply incidental. It means something. Let me try again to illustrate why. If I said, “The government is in the city, the universities are in the city, the media headquarters are in the city, the heads of churches are in the city, the theological colleges and seminaries are in the city, but the word of God came to John in the wilderness,” perhaps you’d start to get the feel of it.

But this is not just a geographical and political reference. It is also about a state of mind. Why do we sometimes say things like, “I need to go bush for a while and clear my head”? The wilderness is not just a place. The wilderness is a state of being that is beyond the fringes of the normal certainties. It is beyond the reach of the status quo. It is a place where we are cut loose from the iron grip of normal expectations and rules and conformities. I’m heading into the desert for a two week retreat in January. I have no idea what might happen. The wilderness is the place where we see with different eyes; a place where new and previously unimagined things can happen; a place where the word of God might break through and change us.

One of the things that means is that we should not be waiting on leaders, even church leaders, to tell us what we need to know and what God is calling us to do. And I say this knowing that I am one. But I know that inevitably, by virtue of the position I occupy as a designated pastor and preacher, I am bound up to some extent in the status quo. I cannot be fully relied upon to be a free and unbiased interpreter of the word of God because I will have trouble seeing where the word of God undercuts my own position and calls people to something new that is out of my control. Maybe in the desert I will be a bit more able to, but Luke is reminding you not to rely on me for that.

So each of you needs to be involved in turning your backs on the would-be authority figures, and listening for the word of God together. Our congregational covenant calls us to non-conformity with the ways of the world, to listen together for the voice of God, and to allow God to call and send us into new areas of mission and ministry. But even the covenant is an attempt to regularise this and so it carries in itself a danger of undercutting our capacity to cultivate the wilderness mindset that would enable us to do those things.

Similarly, our worship services are supposed to be wilderness spaces, desert spaces. The social theorists call it “liminal space”. They say that when any significant transformation happens in a human being or a community, it happens in liminal space, or liminal time. It is the space where we have cut loose from the normal realities and we are taking the risk of living beyond the bounds of the known and safe and predictable and explainable. If the transformation occurs, we don’t just return to the old realities. We come out as new people in a new place. We are changed. The old is gone, and all things are made new. And the biblical reference to the wilderness is exactly the same thing. The risky and uncertain place where we might hear something new and be radically changed by it.

Many of you have experienced worship here being like that. It has cut you free and shaken you to the core. It has touched things deep inside you that you had to either flee or surrender to. But even in this congregation, worship can become part of the status quo of our expectations. We can master the ugly art of resisting its power and forcing it to function as just part of the way things are and ever more shall be so. Our participation in it can become something that makes us feel okay about the present state of our lives instead of being the place where we open ourselves to the purifying fire of God.

Part of entering into the wilderness mindset is giving up the need to be able to explain what is going on. If we are opening ourselves to God, we are going into a place where things are beyond our control and beyond our comprehension. This is actually implicit in the word “repentance”; this thing that John calls us to. The original Greek word that Luke uses is “metanoia”. Meta means to change or go beyond, and noia comes from nous, from which we get nouse, and means the mind or the intellect.

We have somehow come to think of repentance as meaning little more than saying sorry, but that’s at best only a tiny fraction of its meaning. Even the idea that it means “to change your mind” is not enough, because we think of that as just meaning change your opinion, when it means it more in the sense that you might talk about changing the engine in your car. To repent, to change your mind, is to get a new mind.

And this idea of “going beyond” might be helpful, because it reminds us that we are not just looking for new ideas. We are looking for a different kind of mindset that is beyond our normal way of processing information and making decisions. We are looking for the wilderness mindset, the desert mindset, the mindset that doesn’t expect to be able to explain and categorise and judge. We are looking for a mindset that does not seek control and categorisation. We are seeking the mind of Christ, the risky, open, uncluttered mindset that can be captured by the wind of the Spirit and freely taken who knows where.

None of us manage to do that on a continuing basis, but almost all of us have known moments when we were rendered helpless before some awesome mystery, and in that moment, everything looked radically different and all the usual rules were out the window. Maybe it was at a childbirth. Maybe it was being present as a loved one died. Maybe it was sitting on a wilderness mountain top. Maybe it happened in the silence in worship, or as the bread was broken in the Eucharist. Maybe it was on retreat in the desert or in a monastery. Maybe it was in prayer in your own room. Maybe it happened while you were pegging out the laundry. But whenever it happens, those moments are tastes of the mindset that repentance calls us to change to, the mindset that being plunged beneath the water of baptism in the wilderness calls us to rise to. And it is that mindset that will open us to God and enable us to prepare the way of the Lord.

How do we prepare the way of the Lord? I’m only touching on the tip of an answer here, but it begins with “repentance”, a mind changeover. It begins with opening ourselves to the wild possibilities that are beyond the reach of the powers that be, in their arrogant belief that they have the territory all carved up and labelled and under control. It begins with opening ourselves to the absurd possibilities that the breaking of bread and the sharing of wine offer more hope for saving the world than all the politicians and scientists and theologians can ever prescribe. And here and now it might begin with allowing the naive prayers and the quirky and almost nonsensical statements of faith to carry us into the wilderness and open us up to the coming of the Lord.

0 Comments