A sermon on Luke 1: 39-55 by Nathan Nettleton

At this time of year, unless you lock yourself in your house and never come out, it is impossible to avoid the great summer holiday festival known as Christmas. Its symbols and sounds intrude into absolutely everything – what people wear, what people talk about, what people eat, what’s decorating the shops and houses, what music is playing on the radio, and what’s arriving in your mailbox. Even here in Melbourne, its ability to impose itself inescapably on our consciousness exceeds that of Grand Final Week, the Grand Prix and Melbourne Cup Day.

On the day this great festival ends, the churches will begin a twelve day celebration of the incarnation of God in Christ, a celebration which rather confusingly goes by the same name: Christmas. Unlike the great summer festival, it will go almost unnoticed. To the uninitiated, it will seem really strange that we are not singing Christmas carols in here this week, but that we will be on the next two Sundays when all the Christmas decorations will have gone from the shops and the Christmas trees will be lying on the nature strips.

We did sing “Joy to the World” before, and people have come to think of that as a Christmas carol, but it’s actually an Advent hymn – there are no Christmas references in its lyrics at all.

The relationship between these two festivals has always been a rather confused one. Unlike many of my peers, I don’t think there is much mileage in the “put Christ back into Christmas” campaign.

The two festivals began as separate events. The pagan festival, marking the winter solstice in the northern hemisphere and including decorated trees, predated the birth of Christ by centuries. The attempt to merge the two celebrations into one was only ever partially successful, and it is completely collapsing again now that the flawed idea of a “Christian society” has been discarded.

I’m not opposed to participating in the secular celebrations. The summer solstice is as good a time as any for a party with friends and family, so enjoy it or endure it, whichever works for you, but at the same time, we are preparing for a quite different celebration of God’s miraculous and mysterious presence among us. And that twelve day celebration doesn’t even start until tomorrow night.

One of the things that maintains the confusion is that both festivals make use of nativity scenes and songs about the birth of Jesus. It grates a bit, but it is hard for the church to complain too loudly about this borrowing, because it was us who initiated the attempted merger, and we did it by borrowing much of the symbolism of the pagan festival and putting it to use in our celebrations. We tried to swallow their festival into ours, and they responded in kind. And the judges now have them well ahead on points!

But the fact that the world has been more successful at paganising our celebrations than we’ve been in Christianising theirs makes this season of Advent all the more crucial for our spirituality. We have to work a lot harder to hear what God is saying in these stories and songs, because it is nothing like what the local council and the television programmers and the Coles-Myer marketing department are saying when they use them.

This Advent season reminds us that to understand the story we need to read it backwards. We prepare ourselves to rightly celebrate the first coming of Christ by reflecting on what it will mean when he comes in glory to turn the world on its head and put all things right. Only in light of that expectation can we know what we are doing when we worship the God who comes to us in the baby of Bethlehem.

The story we heard tonight from the gospel according to Luke is one of the stories that sounds this warning loud and clear, and it is consequently one of the stories you are not likely to hear from anyone else but the Church. It is also the first story we’ve had in this Advent season which actually mentions the baby Jesus, albeit at this stage still in utero, and we will perhaps get closest to understanding its call to us by comparing and contrasting it to the way the Jesus stories and songs are used in the secular summer festival.

You see, in the shopping mall music and Christmas card nativity scenes, the one thing that Jesus’s presence does not stand for is an expectation of radical, earth-shattering change. Quite the opposite, in fact. He is depicted and sung about in order to keep things more or less the same as they have always been.

Although Jesus has no life-shaping significance for the vast majority of Australians, and has no particular relevance to how they celebrate the festive season, the songs and pictures are retained because they are symbols of continuity with the past. They serve to reassure people that even though the pace of change in our world can be bewildering and disorienting, some things stay the same and can be relied on to keep staying the same.

Even when our planet is beginning to fry, and the world is tearing itself apart in war, and our kids are resorting to anti-depressants, and even nice western democracies like ours deport people knowing they will be tortured and killed; even in the midst of it all we can cling to the reassuring certainty that each year we will lax lyrical about families and cute babies and sing of peace and goodwill on earth. And Karl Marx thought it was Christianity that was the opiate of the people!

The great deception is that the world sings of peace and goodwill to all precisely to avoid having to make the changes that will be necessary to bring peace and goodwill into reality.

Often at this time of year you hear some more modern Christmas stories too. Perhaps you’ve heard the one about the soldiers in World War One who heard each other singing Christmas carols from their opposing trenches, and they all emerged from the trenches, shook hands, swapped stories of family and home, and celebrated Christmas day together. It is a lovely heart warming story, until you remember that the next day they went back to trying to blow each others brains out. Their Christmas day peace and goodwill had served only as a sentimental and reassuring maintainer of normality, and normality includes senseless killing and nations at war with one another.

Luke’s story of pregnant Mary visiting pregnant Elizabeth almost seems to be lulling us into another haze of sentimentality. We have two overjoyed expectant mothers getting together to share their happiness. We have lovely details about a baby seeming to join in the happiness, bouncing for joy inside the womb, and the mothers, as mothers do, suggesting that the baby’s kicking is actually an indication that the baby is responding with deep theological insight to the events taking place around it. It could almost be any two expectant mothers. All is cute and lovely. Perfect material for affirming that all is well with the world. Peace and goodwill and keep everything safe and nice.

But then Mary breaks into song. Chances are it was a song they already knew and Elizabeth joined in too. Maybe the babies even bopped along in their wombs. And this song changes the picture big time.

The words of the song seem to be jarringly juxtaposed against this scene of maternal bliss. And, as is pretty much always the case when the Bible or the liturgy juxtapose things against each other in ways that startle and jolt us, the deepest meaning is in the juxtaposition itself, not in the two parts taken separately. The two things which seem to resist being put together like two same poled magnets, need to be held together and kept together until we begin to see God’s mysterious truths emerging from the juxtaposition itself.

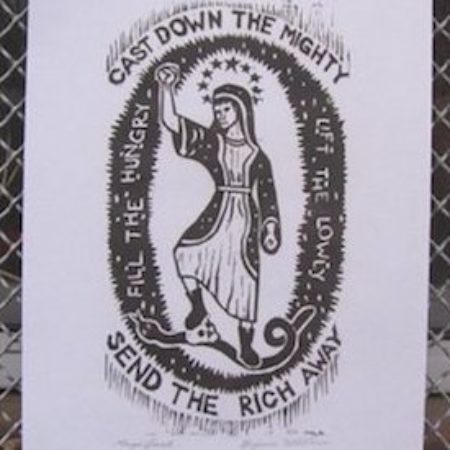

In this song, we have a radical, earth-shattering vision of the world made different. In this song, Mary’s vision moves quickly from the Lord being generous and merciful to her, lowly peasant though she is, to the Lord upending the world as we know it, tearing down the powerful from their thrones, trashing the plans and schemes of the proud and wealthy, and lifting up the poor and hungry and crowning them with honour and glory.

This is the kind of song that tyrannical regimes go to great lengths to prevent the peasants and workers from singing. From El Salvador to Burma to Uganda you will find stories of military regimes killing or maiming the poets and folk-singers, and violently breaking up gatherings whenever the poor and oppressed begin to sing. Mary’s song is just the sort of revolutionary vision that sends shivers down the spines of those who profit from the way things are here and now.

Mary’s song is full of visions of prime ministers and presidents and dictators being ousted from power and left with nothing. It is full of chief executive officers being handcuffed and jailed for their profiteering. It is full of millionaire tycoons having to beg on street corners. And it is full of asylum seekers being made welcome anywhere and everywhere; the homeless being given the keys to the Toorak mansions; and the fearful and frightened laughing and dancing in the streets with nothing and no one to be afraid of ever again.

And what the gospel writer, and indeed the whole season of Advent, is asking us to do is to hold that disturbing, unsettling and wildly hopeful vision in constant tension with this seemingly innocuous vision of a baby about to be born and a couple of blissful expectant mothers.

Actually, most expectant mothers know that a new baby is going to turn their lives upside down and inside out. Life will never be the same again. But the gospel writer wants to drive home to us the message that with the birth of this baby, the whole world will begin to be turned upside down. The status quo, the world as we have known it, is going to be upended as surely and wildly as the money changer’s tables in the Temple.

The gospel writer and this season of Advent are preparing us for the Christian celebration of Christmas by sounding the warning loud and clear: do not kneel and worship this baby unless you are ready to embrace the vision of the whole world remade in the image of God. Do not come and adore him unless you are ready to have your life and your world and everything you hold dear turned upside down and shaken and reshaped to fit a world where justice and truth and reckless hospitality reign. Do not come with your gifts to honour this newborn king unless you are ready to be caught up in the wind of God’s Spirit and blown who knows where.

Because this sweet and harmless little baby nestled in Mary’s womb is the One who comes to do God’s will, to bring the world to its knees, and to upend the world as we have known it. This baby is the powerful presence of God whose kingdom will come and whose will shall be done on earth as in heaven. And that’s not good news for retailing giants or men of war, but it is very very good news for all who suffer under the weight of the sin of the world and cry, “How long, O Lord, how long?”

How it will happen, we can barely imagine. When it will happen is not ours to know. But that it draws near as surely as the birth of a baby in a swelling womb, is our promise and our hope and our deepest craziest desire.

0 Comments