A sermon on Exodus 32:1-14 and Matthew 22:1-14 by Nathan Nettleton

One of the things I’ve been asked a number of times in recent weeks since our support for marriage equality started attracting a lot of social media attention is, “What if you are wrong? What if you end up standing before God at the final judgement and God holds you accountable for condoning sin and turning other people away from the path of righteousness?”

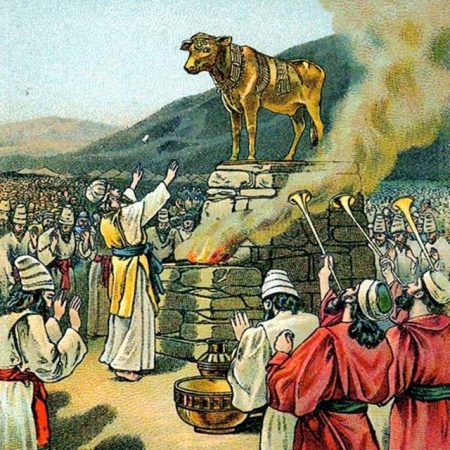

It’s a fair question. There is no shortage of material in the Bible that speaks of the fierce holiness and the terrifying anger of God, and falling short of the expectations of this God is often portrayed as a priority ticket to a violent and gruesome end. We heard two such stories tonight. In the parable that Jesus told in our gospel reading, it is probably the rejected and silent non-conformist guest who is the Christ figure, suffering violence, but it has been more common to conflate this parable with a similar but markedly different one in Luke and see the angry violent king as representing God in very scary terms. So we may be mistaken to see that one pointing to a terrifying God, but there is no such question over our first reading from the book of Exodus. That story clearly speaks of God as being white hot with anger and ready to consume the people in fire.

So why, people are asking me, am I prepared to support something that has traditionally been seen as sin and so risk falling into the hands of such a fiery anger? One of the things that intrigues me about that question is that it seldom seems to occur to the people who ask it that it could just as easily be asked in reverse. If they are afraid of a fiercely demanding God who doesn’t tolerate mistakes, why are they not equally scared of being wrong themselves, and eventually having to stand before this God accused of “tying up heavy burdens, hard to bear, and laying them on the shoulders of others” (Matthew 23:4)?

I suspect that the answer takes us into the heart of what is really going on in this story about the Hebrew people and their golden calf. I actually want to focus more on what is going on for the people than on the questions of God’s alleged violent anger, but it would probably be irresponsible to say nothing about it. So for the record, let me just say that although this story is still attributing this violent anger to God, it is a good example of the way the Bible stories are beginning to reconsider that question.

It is not yet able to conceive of God as responding to sin with anything other than fiery rage, but it tells us that Moses is able to talk God into calming down and showing mercy. If we had read on further, we would have heard that there was still a savage massacre at the hands of the priestly Levite clan, but you can see the story wrestling with the question of whether this massacre really reflected God’s anger or just the violence of the people. The writers are not sure, but the question is clearly emerging.

That question continues to grow as the Hebrew scriptures unfold over the subsequent centuries, and by the time we get to God’s definitive self-revelation in Jesus, we can see why Matthew’s gospel tells us that “the kingdom of heaven suffers violence, and the violent take it by force” (Matthew 11:12). The violent ones try to grasp God’s endorsement for their violence, but Jesus refuses to clothe violence in the robes of legitimacy, and so the violent rulers turn their wrath on him and cast him out of their bloody banquet.

I could easily develop that theme more fully from these passages, but it is probably a bit of an overworked hobby horse of mine already, and I really want to explore what is going on for the people with this golden calf incident, and ask whether very similar dynamics play out in our lives too. And I suspect that that question about my alleged risk-taking is quite closely related to it.

You see, it strikes me that we usually think of this story in ways that distance ourselves from it. We see it as some weird primitive form of religion that is nothing like anything we would ever do. There are plenty of people nowadays who think that any form of belief in God is similarly weird and primitive, but those of us who do believe in God certainly tend to think there is a big gap between that and this kind of blatant idolatry. We can’t imagine ourselves turning our backs on the living God in favour of a handcrafted model cow. But maybe we are missing the point. Maybe what’s going on in this story is not quite so simple.

If we look more closely at the text, the story begins to look a little different. There is a big clue in verse five, but it is often a bit obscured in the English translation. It tells us that when Aaron presented the golden calf to the people, he declared that the religious festivities around the calf the next day would be “a festival to Yahweh,” Yahweh being the specific revealed name of the living God of Israel as opposed to a generic word for any old god.

What that tells us, if we have ears to hear, is that Aaron and the Israelites didn’t think they were abandoning Yahweh and turning instead to the idols of the nations around them. They thought that they were using this beautiful golden statue as a way of connecting with Yahweh in much the same way that they later used the Ark of the Covenant and the Temple. So what is going on here?

Well, let’s back up a little bit. Some of us are probably not very familiar with these stories and need a bit of context. We’ve been hearing the back story in our readings over the last couple of months, but let me briefly recap. The Hebrew people had been held as slaves in Egypt, and God had inspired Moses and his brother Aaron to lead the people in a mass escape from slavery. Having escaped, they are now on route to their promised homeland, but they have years of travel ahead of them before they get there.

At this point in the story, Moses has disappeared on them. He has gone up to the top of Mount Sinai to meet with God, but what the people below are seeing is that there appears to be a raging bushfire or a volcanic eruption or something on top of the mountain where Moses has gone. And now he has been gone for forty days and they are, quite reasonably, beginning to assume that he’s not coming back. The mobile coverage was crap in those days, so they couldn’t text him to see if he was okay. After decades of feeling abandoned by God in Egypt, they’ve had a few months of feeling a real connection to God through this man Moses, but now they’ve lost him. God is suddenly feeling very distant again. How are they going to connect to God now without Moses?

Now that’s not such an unfamiliar feeling, is it? You can see feelings a bit like that in our own context, and on both sides of things like the marriage equality debate. For many LGBTQ people, the past decade or two have been much better than the times before. The promised land of openness and honesty and being accepted seemed to be arriving. And then suddenly, the wider public is given licence to pick over their lives and relationships and express whatever humiliating opinions they like, in the name of informed national debate. Back in the wilderness, lost and without leadership.

And yet many in the churches are feeling much the same, despite often being on the opposite side of the debate. After centuries of being looked up to as the unquestioned authority on what was good and decent and acceptable, and of being seen as the sole providers of saving access to God, suddenly it has all fallen apart. It may have taken decades or even centuries, but it feels sudden. Most Australians now say they think religion does more harm than good, and the history of religious wars, corruption and sexual abuse make it hard not to agree with them. How can we not wonder whether the failure of the Church isn’t evidence of the failure of God? Perhaps God’s power has failed, or perhaps God has given up on us and abandoned us to our fate. We weren’t well prepared for finding ourselves this lost in the wilderness.

I got into a lift while making a hospital visit on Friday, and there was a man there in a wheel chair being transferred to a different part of the hospital. And just as we were about to get out, I suddenly realised that his wrists and ankles were both secured with police restraint cuffs. Geez. I reckon if you’re being wheeled through a hospital in a wheelchair wearing a hospital gown and restraint cuffs on your wrists and ankles, you’re probably not feeling too good about where your life has got to at this point in time. But you don’t have to literally be there to know that feeling. And when we feel that desperate, we’ll grasp at just about anything that will make life feel a bit more like it is going somewhere certain and worthwhile.

I reckon that is basically what was going on for the Israelite people, stumbling through the wilderness and now suddenly without the man who symbolised and guaranteed their safe relationship with God who might otherwise either abandon them or burn with rage and massacre them. What they felt a desperate aching need for was some visible tangible sign that God was among them, that they were still the chosen ones, and that there was some certainty about what was happening and where they were headed. And so Aaron set about responding to their need by creating a suitably beautiful and impressive symbol that would reassure them and give them hope.

Now given that the Ark of the Covenant and the Temple later fulfilled an almost identical symbolic function in the religious life of Israel, you might reasonably wonder why, if what I’m saying is true, God would be so angry about their golden calf. Why is this handcrafted image so wrong when the later ones are not? I’m not going to pursue that question in detail, but it is a good question and suffice it to say that the answer appears to have something to do with there being a big difference between waiting on God to offer us symbols to use, and just taking matters into our own hands and making stuff up.

The question that I think is more important for us to look at right now is what sort of things we are tempted to similarly grasp at when God feels distant and we feel insecure and afraid. What will we grasp at to make ourselves feel sure we are on the right side and we are being blessed by God?

Sometimes we do everything we can to surround ourselves with a culture that feels strong and uniform and really going somewhere. We merge three or four struggling little churches into one big strong church, not so much because of the economies of rationalising resources, but because we so want to belong to something that feels significant and cutting edge and influential. It’s big enough to feel ourselves securely held and happening enough that we can happily ignore the statistics that say churches are still declining. Ours doesn’t feel like it is. We’re part of something that looks and feels blessed by God.

Even in the wider secular society, we can find ourselves doing something similar. Those of us on the “progressive left” side of society are especially susceptible to this. I don’t know how often I hear one of my peers saying, “I don’t understand how the Pauline Hansons and Corey Bernardis of this world keep getting elected. I don’t know anyone who would vote for them.” Or “I don’t know how this marriage equality thing is even an issue. I don’t know anyone who doesn’t support it.” Welcome to the comfortable golden calf bubble of our own making. We create a little social world in our own image and without being able to see beyond it any more, we convince ourselves that all is well and we are shocked by anything that hints that things are not as they seem.

We can even turn the Bible into a golden calf. This is surprisingly common, and I bump into this one all the time too. Unable to cope well with a genuine personal relationship with a mysterious God, with all the vagaries and uncertainties that are common to any personal relationship, we grasp for something that can give us that elusive absolute certainty about what God thinks and wants from us about anything and everything. And we end up treating the Bible as though it was the last will and testament of our dearly departed God. The relationship is no longer truly personal, but we have the written will and we’re honouring our dearly departed God by following its instructions to the letter and making everything just how God would have wanted it. And the more frightening the rapidly changing world becomes, the more tightly we cling and the more certain we become that we have chapter and verse right here in the Authorised Golden Calf Version to banish our doubts and insecurities.

My friends, the place where everything was certain and predictable and reliable was the place of slavery. Like the people of Israel, we often miss the safety of just being oppressed and always knowing that someone else is in charge and that we don’t have to be responsible for working out what what should happen next. But God has called us out of slavery and called us to rediscover our relationship with God and with one another in a strange new place of freedom. And when that happens, it takes time to trust that freedom and to believe that a God who doesn’t stand over us like a slavedriver or a tyrant king is nevertheless with us, lovingly trusting us to live boldly and creatively and freely.

Relax. Bask in God’s love. Learn from Jesus what freedom looks like. Laugh. Sing. Pray. Dance. Eat and drink. Make love. Make mistakes. The promised land is welcoming those who are bold and free enough to dance on in. But if you stand at the border and fret over whether you might have got it wrong, you’ll soon find that you have turned the promised land into just another place of slavery in which all you’ve done is comfort yourself that it is good slavery instead of evil slavery. All those golden calves we made for ourselves were understandable, and sometimes beautiful and impressive and comforting. But they are heavy and unnecessary and they hold us back from the joyous overflowing fullness of life that God has called us to. Let them go, and live!

One Comment

Even in the wider secular society, we can find ourselves doing something similar. Those of us on the “progressive left” side of society are especially susceptible to this. I don’t know how often I hear one of my peers saying, “I don’t understand how the Pauline Hansons and Corey Bernardis of this world keep getting elected. I don’t know anyone who would vote for them.” Or “I don’t know how this marriage equality thing is even an issue. I don’t know anyone who doesn’t support it.” Welcome to the comfortable golden calf bubble of our own making.

Yep yep yep….

Hard to hear AND true!

Thanks for another amazing sermon Nathan.