A sermon on Jeremiah 33:14-16 by Nathan Nettleton

A video recording of the whole liturgy, including this sermon, is available here.

The season of Advent, which starts today, is all about hope and anticipation. It is a time of dreaming dreams and waiting expectantly on God. It is a time when we prayerfully imagine the new things God is doing, when we stand on tip toes and crane our necks to catch a glimpse of the dawning day of God’s justice and peace, of God’s coming kingdom.

But whatever the season of Advent might be wanting to say, this is not an easy time to feel hopeful in the Church, is it? In fact it would be a very easy time to be feeling thoroughly depressed about the state of the Church and about the prospects of any sort of positive future for it.

There are any number of indicators pointing in all the wrong directions. In this country, and across most of the western world, rates of church membership and attendance are spiralling deeper and deeper into decline. Some major denominations in this country face almost inevitable extinction within a decade or so because their membership is almost entirely elderly and they have few young people coming in.

In some parts of the world churches are growing rapidly, but many of us have mixed feelings about that because so much of it is exhibiting the kinds of hostile conservatism and ungracious militancy that we have become embarrassed to be associated with. But that embarrassment is nothing compared to what we are feeling over the way the Church is getting itself into the papers for all the wrong reasons of late. So many priests and pastors and church institutions that people trusted and looked up to have been exposed for the most callous crimes against the most vulnerable human beings and for covering up their responsibility and protecting the perpetrators.

No wonder so many of our friends and acquaintances are incredulous that we would want to have anything to do with the Church. So, in the face of all that decline and shame, what wonderful future could we be anticipating? Is talking about hope in God’s future anything more than a bit of escapist fantasy for a Church that’s in deep denial of its own reality?

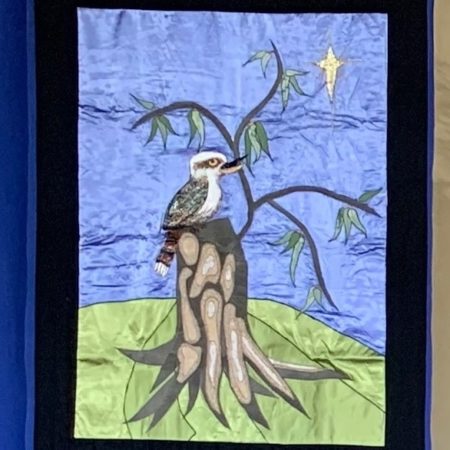

There was an image in our first reading tonight which tells us that this is not the first time God’s people have faced such agonising questions and also tells us something of the nature of the hope that can meaningfully be expressed in such times. It is an image that has come to be so commonly associated with the season of Advent that it is represented in the design of this Advent banner that used to hang in our church at this time of year. No, not the kookaburra, but what he is perched on: a cut down tree stump with new growth sprouting from it.

The classic Biblical expression of it was not in tonight’s reading from the prophet Jeremiah, but from the prophet Isaiah (11:1) who says “a shoot shall come out from the stump of Jesse, and a branch shall grow out of his roots.”

Although tonight’s passage from Jeremiah doesn’t actually mention the stump, when it speaks of God “causing a righteous Branch to spring up,” it is appealing to the same picture. These were not isolated sayings. They drew on a well known idea that was very much alive in the popular imagination of the day. It was still a well known image in the early days of the Church when Paul quotes it in his letter to the Romans (15:12): “The root of Jesse shall come, the one who rises to rule the Gentiles; in him the Gentiles shall hope.”

Now it was certainly a well known image back then, but it is not so well known now, so some of you may be needing me to explain that the name “Jesse” refers to the father of the early Israelite King David. So a new branch springing from the root of Jesse firstly suggests a new and worthy king appearing after the royal line that began with David has become corrupt and been cut off. And both the prophets immediately speak of this new branch being one who will “bring about justice and righteousness in the land.”

So what is first imagined by the prophets is a new king arising from the failed monarchy and proving to be a good king who does what is right. “The days are surely coming, says the Lord, when I will fulfil the promise I made and cause a righteous Branch to spring up for David; and he shall execute justice and righteousness in the land.”

Now I want to reflect for a minute on one of the things that happens in this passage and these prophesies in general. These names, like the “righteous branch” or at the end of the passage the one who will be called: “The Lord is our righteousness”; these names or titles seem to keep shifting in who they are being applied to.

On the one hand there is clearly an expectation that they refer to one person, a new king, born from the line of David. But on the other hand, they also keep getting applied to the nation as a whole, as is indeed the case with the last line of our passage. Is the anticipated messiah a single individual, or is the people as a whole chosen and anointed by God to bring salvation and blessing to the world? The words of the prophets keep sliding back and forth between the two.

And indeed we see the same thing happening in the writings of the New Testament. Messianic identity is related firstly and seemingly exclusively to Jesus, but then we start to get all these images and descriptions that speak of the church as “his body” and as the bearers of his light in to the world. The Messiah, it seems, has so identified himself with us, his church, that again the language of God’s chosen anointed one keeps sliding back and forth between Jesus and us.

Athol Gill used to remind us that whenever we prayed and asked God to act in the world, we had better be aware that God might just ask us to be the answers to our own prayer. And so indeed it seems that even when we pray that the messiah might come bringing salvation and blessing and hope to the world, God might respond by calling us to be a messianic people who do just that. So perhaps it is not too presumptuous to think that we might be being called to be a righteous branch springing up in a time when the church seems to be disastrously cut down and reduced to nothing but an unpromising stump.

Of course, any sort of chosen people theology carries some serious dangers. The long drawn out bitter war between Israel and Palestine, and particularly its last horrific year, is a loud warning of what happens when a people who identify themselves as God’s chosen people forget that God chooses people, not to be God’s privileged favourites, but to be a blessing to the world, to bear witness to God’s all-embracing love and mercy that never plays favourites but lays down its life for all without exception and without limit.

And so clearly any call to us to be a new branch springing to life from the old stump is not to be heard as a claim of special privileges or favoured status, but as a call to radical faithfulness, to a self-sacrificial living out of God’s justice and righteousness as we proclaim and share God’s overflowing love and mercy.

So, the sort of hope we lean into in this season of Advent is no escapist fantasy of imminent glory days when the Church will regain its lost prestige and power and conquer the world. And neither is it a denial of the tough realities of our present predicaments.

Both this passage from Jeremiah and the passage we heard from Luke’s gospel sound their messages of hope against a backdrop of earth-shattering troubles and death and destruction. And this image of the new branch that emerges despite the death and disaster is an image of a fragile hope, of small and seemingly insignificant beginnings, or re-beginnings.

But it is also an image that is at the heart of the gospel we preach. For it is an image that captures a pattern of how God operates over and over down through history, and which has been revealed most clearly to us in Jesus the Christ, the righteous branch from the stump of Jesse. For what the prophets told us and what Jesus has shown us is that even when God’s work is destroyed by the corruptions and scandals and failures of God’s people or by the attacks and violent hatred of others, there is nothing so dead or destroyed that God cannot bring life bursting forth again where only death reigned.

This is the hope that was born in a manger in Bethlehem. This is the hope that was born again from the tomb in the garden. This is the hope for which we pray, and for which we offer ourselves, that we might be born again as a new branch of God’s fragile but irrepressible life and love in the world.

0 Comments