A sermon on Mark 9: 30-37 by Nathan Nettleton

Kids can drive you crazy at times. Perhaps to help deal with his frustrations over the behaviour of his kids one day, a bloke called Ian Frazier translated some of the things he said to his children in frustration into the language of the ancient Laws of Moses. Here are a few samples, but if you want the full set, you can find it here.

- If you are seated in your high chair, or in a chair such as a greater person might use, keep your legs and feet below you as they were. Neither raise up your knees, nor place your feet upon the table, for that is an abomination to me. Yes, even when you have an interesting bandage to show, your feet upon the table are an abomination and worthy of rebuke.

- Sit just as I have told you, and do not lean to one side or the other, nor slide down until you are nearly slid away. Heed me; for if you sit like that, your hair will go into the sauce. And now behold, even as I have said, it has come to pass.

- Do not scream; for it is as if you scream all the time. If you are given a plate on which two foods you do not wish to touch each other are touching each other, your voice rises up even to the ceiling, while you point to the offence with the finger of your right hand; but I say to you, scream not, only remonstrate gently with the server, that the server may correct the fault.

- Likewise if you receive a portion of fish from which every piece of herbal seasoning has not been scraped off, and the herbal seasoning is loathsome to you and steeped in vileness, again I say, refrain from screaming. Though the vileness overwhelm you, and cause you a faint unto death, make not that sound from within your throat, neither cover your face, nor press your fingers to your nose. For even now I have made the fish as it should be; behold, I eat it myself, yet do not die.

Children can bring out the best and the worst in us. They can be the most precious gift in the world, and they can drive you to the brink of despair. In the gospel reading we heard tonight, Jesus speaks of children, and there will have been many sermons preached around the world today about how sweet and lovely children are and how we should all be more like them. This is not one of those sermons! And in part, it is not going to be saying that because that is not what Jesus says in the passage we read.

When you have become moderately familiar with the Bible, one of the traps is that you can hear a passage, recognise it and mistakenly equate it with another passage that is similar but a bit different, and think you’ve got it sussed. I read this passage several times before I realised that it wasn’t the one where Jesus says, “Unless you receive the kingdom of God like a child you will not enter it.” That one is a separate saying that comes in the next chapter.

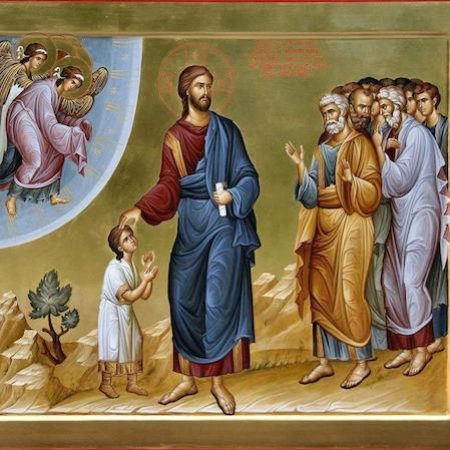

This one is not talking about modelling ourselves on children, but about how we treat children. It does not speak of us receiving the kingdom, but receiving the child. “Whoever welcomes one such child in my name welcomes me, and whoever welcomes me welcomes the one who sent me.”

In a way then, this saying is actually more closely related to the one where Jesus says, “What you do to the least of these, my brothers and sisters, you do to me.” It is about adults and our attitudes rather than about children and theirs, although both are relevant. To the extent that it is about the children, it is saying that they are a sign of the Kingdom, a sign of what the culture of God is like. And therefore, as signs of the Kingdom, our capacity to welcome and honour children is a good measure of our capacity to welcome and honour the culture of God.

It is difficult to hear this with anything like the force it would have had in the days when Jesus said it. We are in a different time in a different culture and the general attitude to children is very different. In those days, children were regarded as little more than pieces of property. Their status was about the same as that of slaves. They were non-persons.

To suggest to adult male disciples that children should be taken seriously and that their treatment of these non-persons was in effect their treatment of God would have been utterly inconceivable. Even twelve centuries later, when Thomas Aquinas was asked who you should rescue first if there was a fire, he answered, “First your parents, then your spouse, and last of all your children.” Today we would probably answer in the exact opposite order, and that change makes it difficult for us to even imagine how Jesus’s words would have been heard.

Some social commentators suggest that the turn around is so complete that it can be said that nowadays we worship our children. The word “worship” of course is not so much referring to a religious activity here, but is pointing to the thing which we most value, the thing which we orient our lives around, the thing for whose pleasure we will sacrifice anything, and against which we will tolerate no offence or blasphemy. I remember Margie being a bit doubtful when she first heard the comment that people today worship their children, but when she bounced the idea off a few of her friends who had kids, they just said, “Oh yeah, that’s me alright.” The idea wasn’t even a surprise to them; just a statement of the obvious.

But that’s not the whole story is it? I don’t think Jesus is suggesting that we should turn our children into the household gods and bow down to them, indulging their every whim. And in fact, the social commentators who point out this trend were not applauding it, but suggesting that it is producing a generation of screwed up, selfish, dysfunctional kids. This is not a lecture on parenting, though, so I am not going to try to address the issues around that.

I just want to make the point that this change has not meant that we are any closer to living what Jesus is asking of us here. Perhaps part of the reason for that is that our worship of our kids is usually quite individualistic and self-absorbed. We worship our kids, if we have them, not other people’s kids. Other people’s kids are, at best, convenient playthings for our children, and at worst just a pain in the neck.

We are still quite capable of treating other people’s kids as non-persons, sweeping their concerns and even their presence out of our sight and out of our minds. When they intrude, they are a distraction from the more important needs and agendas of we more important adults. Perhaps then, it is other people’s kids that Jesus would want us to look to as signs of the culture of God. And in case you are thinking, “They chose to have kids, let them deal with them,” please hear that this challenge is just as strong to those who have kids. It is challenging the parents not to relate Jesus’s words to their own parenting, but to the welcome and honour they give to kids who are not their own.

Perhaps it is the child to whom we have no blood-ties and no community obligations who comes to us as a sign of the culture of God and who is the measure of our welcome and honour of Christ himself. Perhaps it frightened child whose mum checked into the women’s shelter last night. Perhaps they are the children our government locked behind barbed wire and razor ribbon on Manus Island and referred to only as illegals and non-citizens. Perhaps it is the hyperactive child whose tramping feet or shrill voice kept breaking into the silence of your contemplation and prayer in the church. Perhaps that voice was actually bearing the word of God as it tried to break through your defences.

Perhaps it is these children who Jesus is gathering into his arms and saying to us, “Whoever welcomes one such child in my name welcomes me, and whoever welcomes me welcomes the one who sent me.” Could it be these children, rather than the ones we are genetically coded to feel responsible for, who come to us as signs of the Kingdom?

They come vulnerable and fragile. They don’t demand that we take notice of them or treat them with honour. They are fairly easy to ignore most of the time, and when they do intrude on our consciousness, they are easy to dismiss as someone else’s responsibility. Perhaps they really are signs of the culture of God: fragile, not forcing itself on us, easily ignored, and if of any concern at all, then probably someone else’s.

If we are to take seriously what Jesus is saying here, these children are to us something like what the bread and wine is to us at this table – signs of the life of God – signs which we can receive unworthily and mindlessly, or in which we can recognise the fragile presence of God and receive as both a gift and a call to totally reorient our lives.

Perhaps the main difference is that, unlike the bread and wine, the children will detect how we regard them and respond in ways that reveal the truth. You can’t fake it with children. They pick up very quickly who loves them and treats them with joy and respect, and who sentimentalises them and patronises them in a parody of care, and who simply pushes them aside.

When Jesus wanted to illustrate his point with a child, there was one close at hand and only to happy to hop onto his lap. Kids were always coming to Jesus, despite the best efforts of adults who thought them too unimportant. The kids knew that Jesus took them seriously and that they were safe with him. That’s all he’s asking of us. Simple request. Probably a lifetime project to live it out. But the culture of God is like that!

0 Comments