A sermon on Luke 19: 1-10 by Nathan Nettleton

A video recording of the whole liturgy, including this sermon, is available here.

The story of Zacchaeus and his encounter with Jesus is both one of the most well known and one of the least well known stories in the gospels. It is both because there are two versions of the story. There is the popular Sunday-school version of the story, and there is the Biblical version of the story. Unlike some other examples, the popular Sunday-school version is not unbiblical or wrong; it is just reduced down to a single layer story and as a result, much is missed.

In the popular version, Zacchaeus is simply another disadvantaged person to whom Jesus reaches out with the message of salvation and reconciliation. Zacchaeus is a bit different from many of the others, because he is a wealthy man, but he is disadvantaged because he is unusually short and because he is very unpopular.

Every child can relate to the fears of being left out and ridiculed for being short or unpopular. And so the story goes that Jesus picks him out from the crowd, treats him as a friend, and as a result, Zacchaeus is converted and promises to mend his ways. It’s a feel-good story. The underdog is lifted up and made special, and everyone lives happily ever after.

And you know what? There is nothing wrong with that version of the story. It is quite faithful to the original, and what it says is good and true. More or less so, anyway.

But it glosses over a few details of the original, and so it doesn’t tell us all there is to be told from this story. The most important detail that it glosses over is that this was not a feel good story for most of the participants. Far from it. Zacchaeus was no more popular at the end than he was at the start, and Jesus is distinctly less popular. And the crowd, the crowd all began to grumble. All. Not some of them, all of them. Every last one of those who saw what had happened began to grumble and say “This Jesus has gone to be the guest of one who is absolute scum.”

Now we are quite used to hearing of such grumbling after Jesus goes partying with some outcast but his is different, isn’t it? Because normally we hear that the scribes and the pharisees complained, the religious people, but that the ordinary people rejoiced and praised God for what they had seen. But not this time. This time everybody objects. Absolutely everybody.

You begin to see that Zacchaeus was not just a bit unpopular. He was despised, hated, loathed. He was regarded as the lowest of the low, a despicable scumbag. Being a tax-collector in a Roman occupied state meant turning against your own people and collaborating with the occupation forces. It was probably a bit like the way someone would be regarded today if he was found to be passing on the contact details of children to a pedophile network. Zacchaeus was despised.

And as often happens in a relatively small community, when someone is despised like that, they become the target of all the angst and insecurity and anger in the community. Everything that people are upset and worked up about, they take out on the despised one. People behave as though if they could just purge this person from their community, then all would be well with their lives and their society.

Religious communities are particularly big on doing this because they see the “sinner” as the person who is making God angry and holding back God’s blessings from the whole community, and therefore they believe they are doing a service to God by attacking this “source of evil”. Ask any of our LGBT sisters and brothers about how that works in churches, and they’ll have no trouble telling you what it’s like to be on the receiving end of it. So Zacchaeus is wearing a lot more angst than even his collaboration with the Roman occupation forces deserves.

That’s why nobody was about to let Zacchaeus through the crowd to see who it was who was attracting so much attention. Sometimes crowds are quite happy to let a littler person through to the front. When Acacia was about eleven, and she and I had standing room only tickets for the AFL Grand Final, she was able to work her way through the crowd to a good vantage point at the front by quarter time in a way that I could never have got away with.

But Zacchaeus was never going to be let through. And probably Zacchaeus wouldn’t have wanted to risk getting caught up in the crowd anyway. The Zealots, a Jewish terrorist group of that time, had hit men called Sicarius whose method was to stab traitors and enemies at close quarters in crowds with a short dagger they carried concealed in their robes. For the likes of Zacchaeus, being caught in a crowd could be suicidal. Being up a tree where you could see anyone approaching might have looked silly, but it was a whole lot safer.

So when Jesus calls Zacchaeus down and starts treating the town scumbag as a long lost brother, everybody, just everybody, begins to object and complain. “You can’t treat him like that. If you treat him like that, where does that leave us? Are we worth no more than him? If we don’t maintain our united condemnation and rejection of him, the whole fabric of our society will begin to come apart. It will be anything goes and then where will it all end up?”

Everybody no doubt includes quite a few of the very same people who on other occasions might have been the ones who Jesus would have lifted up and welcomed, in the face of the objections of the upright religious types. Zacchaeus is an outcast even to the other outcasts.

But can you see what is happening here? Jesus breaks the consensus of anti-Zacchaeus sentiment, but in doing that he becomes the replacement target for it himself. Part of the glue that holds the Jericho community together is their shared hatred of Zacchaeus. “We stand united against him, and all he stands for, and woe betide anyone who breaks ranks and shows him any friendliness or compassion.” Even today there laws against offering comfort and support to the enemies of society.

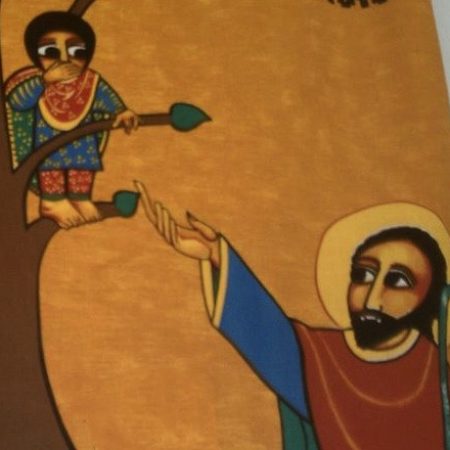

But Jesus does break ranks. He reaches out a hand of friendship and mercy to the far-from-innocent victim and opens up a way for Zacchaeus to turn his life around and make good on the wrongs he has committed. And the personal cost of offering a lifeline to Zacchaeus is huge.

The personal cost for Jesus is becoming the innocent victim himself. When a community has found its identity and unity in who it is against – by who it wants to keep outside its borders, and who it wants to lock up and throw away the key, and who it wants kept off the streets and away from ordinary decent folk – when a community defines itself that way, and nearly every community does, anyone who comes out in support of the target of its angst must be swiftly and equally rejected, or the community will begin to fray at the edges.

And so when the folks of Jericho see the consensus fracture and Zacchaeus lifted above his status as the community victim, they have to turn on the cause of this breakdown, this new outrage. And so: ‘All who saw it began to grumble and said, “This Jesus has gone to be the guest of one who is a sinner.”’

This Jesus. This bloke is undermining the foundations of our society. This bloke is the prime example of everything that is wrong, of all the loss of standards and loss of values in our community. This bloke is a blasphemer, a threat to religion, an enemy of the people. This bloke must be got rid of.

And so another step in the demise of Jesus is taken. And in the same step, salvation comes to another house and saves another victim.

Jesus is passing through Jericho on his way to Jerusalem, and this sort of thing has been going on for some time now. The process is almost complete whereby the people are volatile enough to unite into a mob which chants “Crucify him! Crucify him!”

Victim by victim, Jesus saves us from the hatred and hostility of the world by taking that hatred and hostility on himself and refusing to reciprocate it and allow it to keep festering. Victim by victim, Jesus sets us free to begin our lives over again by placing himself one step closer to the powers of death that will consume him. And victim by victim, Jesus breaks free of death’s stronghold and shows us that there is a way to live and form strong healthy communities without having to keep manufacturing reasons to communally hate someone.

This one too is a child of Abraham and Sarah and can be saved from the fires of fury and rejoined to the community, for the New Human came to seek out and to save the lost.

0 Comments