A sermon on Acts 2:1-21 by Nathan Nettleton

We’ve been having a bit of fun here tonight with languages as we celebrate this story from the Acts of the Apostles about the Day of Pentecost when the Holy Spirit broke through the language barriers and the preaching of the gospel was heard in all sorts of languages.

In the past year, several new languages have been added to our normal Sunday liturgy as we have been joined by new members from different parts of the world. It is exciting that we are becoming a more multi-lingual community, and that we have been able to develop ways of celebrating that in our worship, and of course tonight’s way is just a bit of fun as we flip our normal practice and hear quite a few of us fumbling our way through our second languages, or even if a few brave cases, languages that you don’t speak at all. So, in honour of all this, I want to look at this story of the Pentecost languages miracle and think about what it all really means and why it matters.

Language and identity are often closely bound up with one another. You may have noticed that anger over language is a feature of many racist attacks. Often when we hear about a race based hate attack in the streets or on a train or something, it seems to have begun with the attackers having taken offence over people speaking a foreign language, and they’ve begun screaming abuse at them and demanding that they speak English, and from there it descends into physical violence.

And you may also remember that many of the attempts at repressive assimilation of minority groups, began with attempts to outlaw the speaking of other languages. This didn’t just happen in other countries. It was part of the infamous White Australia policy here, and it was still happening in the not too distant past, within memory of many of us. Listen to this extract from Stan Grant’s extraordinary book, Talking to my Country (p.107-108):

By the middle of the twentieth century my father’s language was dying. It had largely vanished, wiped out by missionaries and government officers who forbade it. My father caught the last utterings of Wiradjuri. His grandfather was among the final keepers of the traditions and ceremonies and he would speak in the bush to my father, educating him in the way he and his father before him had been educated. But once he made the mistake of calling to his grandson in front of the whites. Downtown Griffith was no place for this. The police arrested him and he was jailed. When he came out he refused to speak his language again.

The Boowurrung language of this neighbourhood died out in similar ways for similar reasons. The psalm that we sang it it before is one of the few surviving recordings of it.

Why is language such an inflammatory issue? Why does it stir up such hostility and violence? And what does this have to do with the gospel?

Much of the answer has to do with fear, but it is multi-layered. There are various sorts of fear associated with language. I remember the first time I found myself alone on the streets in a country where I couldn’t speak a word of the language. The thing that surprised me was how terrified I felt. I’ve done it many times now, and it no longer terrifies me, but it did the first time. It wasn’t that I thought the people were unfriendly and that I was going to be attacked or anything. It was just that I am so used to being very confident in my ability to communicate, and very confident that whatever might go wrong, my communication skills will enable me to negotiate my way through the perils, and here I was, suddenly stripped of my most powerful asset, my communication skills. I didn’t even know how to order a sandwich in a shop, and if something went seriously wrong, I would not be able to talk my way through it at all. I felt entirely helpless.

That experience has given me some measure of understanding and even a little compassion for those who feel threatened by others speaking languages they don’t understand. It can be especially sharp if you feel a bit inadequate about your capacity to understand all that is going on around you even in your first language, and if perhaps you are surrounded by a fairly unpredictable and violent local culture.

If violence is an ever present threat, then people speaking in another language could easily be plotting against you, and taking advantage of your inability to understand. So if you are already living in fear, you want to be able to keep track of what is being said and done around you, and so people speaking other languages can make you feel very insecure.

Mostly though, I think it is another layer of fear that leads to these violent attacks on foreign speakers. Most angry violent people live surrounded by lots of other angry violent people, and so they live with a constant sense of danger. At any moment, all that hostility and angst could boil up and explode, and you live with the scary knowledge that it is often pretty random and so you could easily be the target the next time it blows up.

So what we tend to do when we are constantly afraid like that is that we do what we can to make sure that it is someone else, and not us, who is the most likely target. We protect ourselves at the expense of someone else, by treating someone else with suspicion and hostility and aggression in the hope that everyone else will agree with us and thus be united against someone who is not us.

And of course, that strategy, which is always unconscious, is much more successful if the person or group we direct our hostility towards is noticeably different from our group in some way, such as racial appearance or language, and if they are relatively powerless so that our violence towards them is not likely to cause a wave of retaliatory violence that is too big for us to handle. So it is almost always directed towards minorities, and the more distinctive and the more isolated, the more likely they are to be targeted. That’s why there are no neo-nazi skinheads in Jerusalem. Nobody picks on the powerful majority.

Now before we go feeling all superior in our middle-class educated niceness, this phenomena is not just confined to the angry uneducated bogan class. All of us, when we feel under attack will instinctively find ourselves wanting to react by pointing the finger and crying “What about them?” It is virtually universal and it has thoroughly infected all religions including Christianity. It’s not always expressed in violent assaults, but religious groups are notorious for shunning and persecuting groups they identify as “the evil other”.

We have shunned and persecuted Jews, Muslims, Africans, women, divorcees, homosexuals, liberals and fundamentalists. We justify it as being a righteous crusade against sin and wickedness. We are just siding with God who allegedly hates these evildoers. But most of this hostility is driven by the same motive as the racial hatred I was just describing. If someone is going to begin violently purging the world of sinners, we need to make sure that it is some other kind of sinners, not the kind of sinner that includes us. We can reassure ourselves that we are the good people who will be safe if we can identify sin and evil somewhere else. If “they” are the evil ones, then “we” must be the good, so we’ll be exempt when the judgement comes.

And, of course, often this fear is not really about God and some imagined future judgement. It is actually about each other. Fearful of being judged by one another and branded as abominable sinners and shunned or attacked ourselves, we eagerly join crusades against other categories of sin. The Christian left is no better than the Christian right in this regard. Nor the right and left of the wider community. Just look at the wave of hostility directed at Margaret Court in the past few weeks. I share the abhorrence at her vilification of sexual and racial minorities, but if we simply reciprocate her hostility, we are playing the same divisive game. We just point the finger at each other and the world stays divided. We identify “them” as the problem, and because we have identified them as the problem, we feel secure in the knowledge that we are not the problem. But of course, the real problem is the need to keep securing our own identity and security at someone else’s expense.

This is precisely what was so remarkable and extraordinary about what Jesus did. He came among us and willingly stood out as different, as strange, almost inviting us to turn on him as the odd one out, the vulnerable minority who we could all join in persecuting to keep the anger of the mob safely deflected away from ourselves. And by putting himself in that place and willingly surrendering himself to our crusading hostility, he achieved several astonishing things.

He unmasked the great lies of the system – the lie that said that these crusades were authorised by God and conducted on God’s behalf, and the lie that said that we “good” people only ever attack the truly evil and that we can accurately tell the difference between the truly evil and the good that is epitomised by “us”.

And then, beyond simply unmasking the lies, Jesus achieved something even more astonishing. He proved that becoming the persecuted one is not nearly as fatal as we thought. Even crucified to death, Jesus rose up, more alive than ever and even freer than before, to show that we can safely follow him, knowing that the life and love of God will hold us securely. And that security saves us from needing to join in with the finger pointing and crucifying. It sets us free to be part of the solution instead of part of the problem.

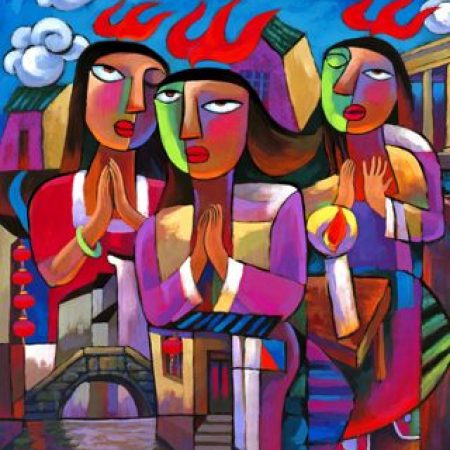

So the Spirit that was poured out on the fledgling church on the Day of Pentecost was the spirit of Jesus. The same spirit that shaped him and inspired him and empowered him to courageously side with the world’s victims, even to the point of becoming the ultimate victim of our hostility and violence. So when this Spirit is poured out upon us, it is a Spirit that has absolutely nothing to do with our desire to divide ourselves up into rival mobs, whether the lines be ethnic or linguistic or sexual or theological. Instead it is a Spirit that breaks down barriers and builds bridges and heals divisions and reconciles former enemies.

So when this wild and crazy Spirit drove the previously fearful apostles into the streets and empowered them to begin preaching the good news of Jesus in the languages of all those they encountered, it was an unmistakable sign of the new culture of God in which all are welcome and our diversity is cause for celebration instead of suspicion.

And when we here find ways of celebrating the diversity of languages among us by regularly including everyone’s first languages in our worship, and today for a bit of fun including some stumbling second languages as well, we are seeking to enact the same sign. It might be just a small thing, but if it is a sign of a bigger transformation happening within and among us, then it will ultimately be no small thing at all. We will truly be allowing ourselves to be blown by the winds of God’s Spirit out of the hellish enclaves of frightened conformity and repressive assimilation, and out into the pathways of Jesus where we rejoice in the rainbow diversity of God’s creation and celebrate God’s reconciling and all inclusive love that heals the world and creates the place of belonging and security we were all longing for.

0 Comments