A sermon on Mark 1:40-45 by Nathan Nettleton

We often don’t know what to do with the biblical stories of sick people being healed, and tonight we heard two of them. Miracles are not something many of us expect to see much. Most of us have seen very few recoveries that could only be explained as miraculous. It is not something we expect to see routinely, and so even if it was something Jesus did routinely, it doesn’t seem to have much relevance to our lives now.

For some people, there is a fierce need to defend these miraculous healing stories as proof that Jesus was the unique and special presence of God in the world, but again, unless the same thing is continuing reasonably frequently, how does that help? Something unique and special happened back then, but what’s that got to do with now?

Others are very focussed on the symbolic meanings of these stories. There is no doubt that the gospel writers used these stories to symbolise things bigger than just physical healings, but sometimes our focus on the symbolic level seems like a way of avoiding our questions and doubts about whether an actual healing took place.

I want to explore the story we heard tonight from Mark’s gospel account about Jesus healing a leper. I’m going to pretty much take it for granted that it actually happened, more or less the way it is told. I don’t pretend to know how. There are many things that happen today that would have been regarded as miracles if observed by people of previous generations. We walk up to glass doors, and they open as if by magic. The connections between things are a lot more complex than we can presently understand. Maybe one day science will have an explanation for all the healings that Jesus did. Maybe it won’t and they will be forever seen as miracles. I don’t really care. Jesus did these things, and understanding how is not nearly as important as understanding why.

Even with that decision made, it might still appear that I don’t know what to do with this story, because I have three different angles on it tonight that could perhaps have been three different sermons, so hopefully I can make them hold together in a way that doesn’t just end up seeming disjointed and undecided. Certainly they all relate more to the question of “why” Jesus did this than to worries about if or how.

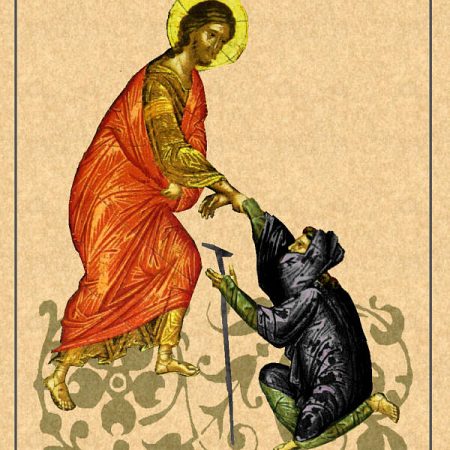

My first question is very much about “why”. Mark tell us that a leper came to Jesus and, kneeling before him begged him saying, “If it is your will, you can make me clean.” And then it says that moved by some emotion that we’ll address in a sec, Jesus stretched out his hand and touched him and said to him, “I will. Be made clean.” And he was.

What was the feeling or emotion that moved Jesus? Most translations say that he was moved by compassion or pity. And that makes perfect sense. That’s what you would expect. And that’s the problem. You see, there are some other early manuscripts of Mark’s gospel that say “moved by anger.” There are not as many of those, so a simple count of the evidence favours compassion.

But one of the things that ancient text scholars say is that simple majorities can be outweighed by a rule that says that the more difficult or problematic version is more likely to be the original. Why? Because it is much more likely that scribes hand copying these texts would try to clean them up. Jesus being angry in this context is harder to explain, so it is more likely that a scribe would tidy it up by describing Jesus as compassionate rather than angry. It is much harder to imagine someone changing it in the other direction.

There are a couple of other more technical things that favour reading it as anger too, but this is not supposed to be an ancient text analysis class, so I’ll spare you the details.

So if anger is part of what moved Jesus to heal this man, what’s that about? Why is Jesus angry? Well the story doesn’t tell us, so what I’m about to give you is my hypothesis, not any sort of proven fact.

I think that Jesus is angry at a cultural assumption that lies behind the leper’s request. Jesus is not angry at the leper, but at the attitude that has infected the man’s thinking from the surrounding culture. You see, the leper doesn’t just ask Jesus to heal him. He says, “If it is your will, you can make me clean.”

Can you hear what lies behind that? How often have you heard people suggest that it might be God’s will that someone be sick or injured, and that it might or might not be God’s will that they be healed? Sometimes it is expressed more subtly in phrases like “Everything happens for a purpose.”

I too have often found myself piously qualifying my prayers by saying, “Lord, if it be your will, heal so-and-so.” Not only is that prayer rather timid and more intent on giving myself an out-clause so that I can explain a non-answer to myself, but it is probably expressing the same attitude that made Jesus angry here. Because there is a whole picture of God lying behind it that sees God as choosing to inflict illness and injury on people, presumably as punishments. And Jesus is saying “Aaagh! No! God is not like that. Sickness and injury are never things that God wills. Don’t let them tell you that.”

So when Jesus says, “Of course it is my will. Be clean,” he is doing more than just healing one leper. He is seeking to heal a cultural assumption, a distorted cultural image of God. Angry at the distorted understanding of God, Jesus wants to heal us all and set us free from this debilitating belief that whatever horrors assail us, it is the will of God.

The second thing I want to explore follows on from this rethink that Jesus is challenging us to make. Note that the language that both the leper and Jesus use is the language of cleanness or purity, not directly sickness and healing. The leper doesn’t ask to be cured, but to be made clean, and Jesus says, “Be clean!” Why does this make a difference? Because this idea of clean and unclean was a specifically religious view of the nature of what was going on. We still use this language a bit when we talk about someone having a dirty little secret, or dragging their name through the mud, or soiling their reputation. These are moral judgements, and we use the language of uncleanness to describe them.

In Jesus’s day, people didn’t think you were unclean because you had leprosy. They thought you had contracted leprosy because you were first morally unclean. So again sickness was seen as a judgement of God. And people kept away from the “unclean”, not because they were simply afraid of getting germs, but because they were afraid of being corrupted, contaminated by moral uncleanness, and thus liable to similar judgement themselves. Moral evil was seen us contagious in the same way that we see germs as contagious. So lepers were required to live outside the town lest they morally contaminate the townsfolk. Good clean people certainly didn’t touch them.

But what does Jesus do when the leper says “If it be your will, you can make me clean”? He says, “It is my will”, and he reaches out his hand and touches the man. “Be clean.”

You weren’t supposed to touch a leper until after he had been certified clean, but Jesus touches him and then sends him off to be certified clean. Do you see the significance? Everyone else thought that uncleanness was the most contagious thing. Touch a leper and the uncleanness would pass from the leper to you. But Jesus thought that love and goodness were the more contagious thing. Touch a leper and the love and goodness would pass through you and overcome the uncleanness of the leper.

Ask yourself what that might look like the next time you hear someone saying “We don’t want those kind of people here, corrupting our culture.” Once again Jesus is trying to heal not just one leper, but a whole culture. A culture that tries to keep itself pure by keeping out those who it regards as suspect, as not measuring up to our values, as different and dangerous. But Jesus is more than confident that truth and love and genuine values will always be more contagious than their opposites. “It is my will. Be touched and made clean.”

The third thing I want to note is a point that I owe entirely to Samara who came out with this brilliant insight during our Host Group meeting the other night. At the time it related more to last Sunday’s reading, but it is here too. Last week we heard that Jesus wouldn’t allow the demons to speak because they knew who he was, and we wondered why he didn’t want anyone else to hear who he was. And tonight we heard him sternly warning the healed leper not to say anything about this to anyone. Again, why? It almost sounds like anti-evangelism. Don’t tell anyone who Jesus really is or what he has done for you. What’s that about?

Well Samara pointed out that this would be completely understandable today in the age of social media, so perhaps the dynamics in those days were not so different. So often today there is a frenzied rush to identify who is saying something, and then to argue about the merits of the person themselves and thereby ignore whatever it was they were saying.

Jesus’s message was not that Jesus is the Son of God. His message was that God’s culture of love and mercy is at hand and that we should all get on board. He didn’t want people getting into fights over the divinity of Christ or the doctrine of the Trinity or any other form of identity politics that the demons might love to generate to distract people from contemplating and responding to his message of a new culture of love and mercy. And equally in tonight’s story, Jesus is already struggling to keep up with the queues of people who just want him to deal with their particular individual need for healing. Jesus is trying to proclaim a message of healing for a whole culture, and he doesn’t need people out there spruiking him as the best solution to your acne problem.

As long as everybody is distracted by who he is and they are all busily tweeting their opinions on whether he’s all that the demons say he is or whether he’s just a snake-oil merchant with some clever tricks, his message will go unheard. His endeavours to get people to recognise and embrace the cultural shift that he is bearing witness to will be lost under all the noise. Which is of course exactly what the demons would have hoped for.

Perhaps these things are signs of just how resistant and resilient the old cultures are. Even Jesus struggled to be heard and understood. People all too readily lapsed into arguing about who he was and the culture of hostility and suspicion and us-and-them divides survived.

The leper and others like him went and told everybody they knew, just as Jesus had feared, and ironically, the result was that it was Jesus himself who, like the lepers before him, was forced to live outside the towns to try to avoid the crowds.

Perhaps you can better see now why I said at the start that I don’t much care for complicated discussions about the nature of miracles. Such discussions can end up being exactly what Jesus was trying to avoid here: distractions from the message that Jesus came to proclaim, the message of a new culture of love and mercy and peace.

It’s the same when we gather around this table in a few minutes. We could easily get distracted by a twitter-storm of debate about the nature of the real presence of Christ, or about who is and isn’t allowed to come to the table. And if we did that, we’d be missing the point. Because this table is not a theological debate. It is a place of nourishment for a new culture, the culture of God’s love and mercy and peace. And if we surrender to that culture and feed on it at this table, we will indeed know the truth, not just skin deep but deep in our bones, that it is the will of Jesus that we be made clean and set free to be new people in a new culture for the life of the world and the glory of God.

0 Comments