A sermon on Matthew 24:36-44 & Romans 13:11-14 by Nathan Nettleton

In the popular imagination, the season of Advent is nothing more than a countdown to Christmas Day, and in fact it has pretty much been swallowed up by Christmas, because most people now think of Christmas as beginning when the decorations appear in the shops, several weeks ago, and ending on Christmas day.

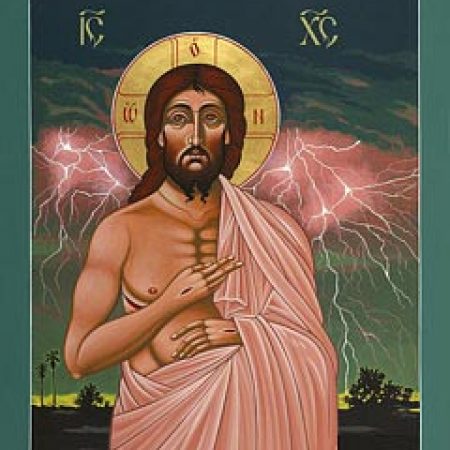

For the church, Christmas doesn’t begin until Christmas Eve and goes for twelve days after that, and from now until Christmas Eve, we observe the relatively unknown season of Advent. And each year, to shock us into remembering that this season of hope and expectation is not just about anticipating the arrival of a baby, Advent kicks off with a set of readings focussed on anticipating the coming of Christ when all is fulfilled and time as we know it reaches its end.

This is not to ignore the expectation of Christ’s arrival as a baby, but it is to remind us not to turn that into a cute baby shower, but to keep sight of the bigger picture in which this baby is born as a part of God’s surprising means of shaking heaven and earth and bringing a whole new world to birth.

Our readings from Matthew’s gospel and Paul’s letter to the Romans both focussed on calling us to wake up to what is going on, to what is coming our way, and to make sure that we are prepared and ready. And in the gospel account, this call includes warnings about the consequences of not being ready, and among these warnings is one of the most contentious and controversial images in all the Bible, an image associated with what has become known as rapture theology.

“At the coming of the New Human, two will be in the field; one will be taken and one will be left. Two women will be grinding meal together; one will be taken and one will be left.” I want to unpack that verse a bit tonight, and see what we might usefully make of it.

The most common interpretation of that verse can be summed up with a quote from a major scholarly commentary that says, “Presumably those who are ‘taken’ are among the elect whom the angels of the Son of Man are to gather at his coming, while those who are left await the prospect of judgment.”

Now the author of that commentary (Donald Hagner) is a great scholar who I love and admire and am privileged to count as a friend, and he visited our church a few years ago, but I’m afraid that the “presumably” at the beginning of that quote is a lot more in need of question than he seemed to realise.

“Presumably” those who are ‘taken’ are the good, while those who are left are in deep trouble. That certainly is commonly presumed, and it has become a key building block of a belief in a final “rapture” when, at the approach of the coming Christ, God will supposedly snatch away to safety those who are chosen and saved, and leave the rest to their grisly fate in a world that is collapsing into a fiery chaos of violence and destruction. This belief has become hugely popular in some church circles, and a series of four movies and sixteen novels called the “Left Behind” series has been based on it and sold over 65 million copies.

Of course, the popularity of apocalyptic literature with spectacular visions of the end goes back to pre-Christian times, and so the popularity of the Left Behind series is far from unprecedented, but the grip of this rapture belief among some evangelical Christians is so widespread that many of the rest of us are quite disconcerted and unsure what to do with it.

Especially since it is a belief that seems to perpetuate a view of God as being very hostile and vengeful towards those who are to be left behind. If you’ve been raised on this understanding of God and of the end of time, and I know some of you have been, a verse like this one from our gospel reading is a very frightening image.

We sometimes make jokes about being left behind when others are raptured, perhaps even being on a speeding bus when the driver is raptured, but those jokes are often masking a genuine anxiety. Will the privileged ones be snatched away to safety and the rest left to fry, and if so, how do we make sure we are not left behind?

Well, I want to put it to you that the rapture reading of this passage is perhaps so wrong that we are in fact supposed to respond to this passage by aiming to be those who are left behind, not to be those who are taken. The 65 million rapture fanatics who bought all those Left Behind books are probably completely wrong about this passage, and so, I’m afraid, is my scholarly friend who wrote the commentary I quoted. Either that, or I’m completely wrong, but come with me and judge for yourselves.

The one and only justification offered in the commentary for the presumption is a verse that comes ten verses earlier that says God “will send out his angels with a loud trumpet call, and they will gather his elect from the four winds, from one end of heaven to the other.”

Now, although these two verses do occur in the same speech, they are not obviously linked and there are several other images in between them, and you will perhaps notice that unless you first presume that they are both talking about the same thing, the first one doesn’t actually say anything about God’s elect being snatched away to some place else. It says that the angels will “gather” the elect, but we don’t normally assume that people who are gathered are thereby vanished away. So any link remains a presumption so far. What evidence can I offer then for thinking that it is being snatched away that is to be the more feared?

Well, two main things, and the first is the historical context. The early apocalyptic literature was born born in an era of persecution. It flourished among downtrodden peoples who were attracted to big cosmic visions that enabled them to interpret their present trials and tribulations as evidence of their favoured status in the eyes of God.

When this gospel was written, Jerusalem had been sacked by the Romans, and in many places Christians were especially fearful of being busted by the next Roman patrol. So, imagine your way into a context where a totalitarian regime is enforcing its will with ruthless efficiency, and death squads knock down doors in the night and those who are deemed to be trouble makers disappear without a trace. And imagine yourself not only in such a world, but as a member of an outlawed faith community who are regarded as trouble makers because of their refusal to call Caesar Lord, and perhaps some of your friends have already disappeared, and with that in mind, listen to the verse again.

“Two will be in the field; one will be taken and one will be left. Two women will be grinding meal together; one will be taken and one will be left.”

So in the world of this gospel’s first hearers, which do you reckon was the more frightening image: to be snatched away, or to be left behind?

And hold that background atmosphere in mind while we look at the immediate context of the verse, not ten verses before, but the verses immediately leading into this one. Here’s what they say:

For as the days of Noah were, so will be the coming of the Son of Man. For as in those days before the flood they were eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage (in other words, just going about the usual business of life unawares), until the day Noah entered the ark, and they knew nothing until the flood came and swept them all away …

Pausing there: the gospel writer tells us that this is the comparison image, and who do you reckon you want to be in the days of Noah when the flood comes: the ones who are swept away, or the ones who are left behind?

They knew nothing until the flood came and swept them all away, so too will be the coming of the Son of Man. Then two will be in the field; one will be taken and one will be left. Two women will be grinding meal together; one will be taken and one will be left.

So, if it is written in days of persecution and death squads, and it is compared to the flood sweeping people away unawares while only one chosen family and a boatload of animals were left behind in safety, it seems to me to be pretty clear that it is “being taken” that we are supposed to be afraid of, and “being left behind” that we are supposed to hope and pray for, and to be awake and alert and preparing ourselves for.

Now, if that’s so, what does it actually mean, and how are we to aim to be left behind and to prepare ourselves for that?

Well, one thing to note in working that out is that nowhere in this whole apocalyptic sermon does Jesus suggest that the chaos and destruction that are coming are caused by God. These things are not described as God’s punishment or God’s vengeance, and it does not even suggest that God has anything to do with them.

This is extremely important, and the fact that it surprises us is the key to why it is so important. Apocalyptic literature, then and now, usually does describe God as the author of the terrible apocalypse, and so this radical shift that Jesus makes is the key to the way he uses the familiar apocalyptic style, but subverts it from within to bring a new message.

Jesus is constantly challenging every depiction of God as the author or authoriser of violence and vengeance, so here Jesus tweaks the familiar apocalyptic imagery to show that the impending flood of chaos and destruction is caused by us; it is simply the natural consequence of human behaviour. We reap what we sow, and if we do not wake up to ourselves, we will destroy one another and render our planet virtually uninhabitable.

You don’t have to look around you too hard now to see that Jesus knew what he was talking about. Even the apocalyptic images of the climate going out of control seem to be coming true around us. And the biggest contributor to this spiral into self-destruction is our constant refusal to face up to our own responsibility for it, and to instead keep deluding ourselves that we can just look after our own, that we only need to worry about those within the borders of our own little circles and to hell with those outside.

And then, whenever things seem to be getting out of hand, in our anxiety and fear we search for scapegoats and rise up against someone who we identify as the source of the problem, the guilty party who we blame for bringing us to the brink of destruction. And thus come the successive floods of persecution as we are swept up in the waves of contagious vengefulness that seem to be targeting some enemy, but which end up carrying us all off in ever increasing floods of self-destruction.

So how are we to prepare ourselves? As always, Jesus is our model, our leader, our example. Over and over we see that Jesus is not swept away in the rising tides of hostility and hatred, but stands firm, calling for love and mercy and gracious hospitality.

When everyone else is swept up in a flood of anger towards Samaritans, Jesus is left behind, holding firm and telling stories of good Samaritans as neighbours, as models of grace. When everyone else is swept away in a flood of pious anger towards a woman caught in adultery, Jesus is left behind, piloting the last lifeboat of forgiveness and reconciliation.

When everyone else is swept up in an angry unity that casts out the lepers, the demonised, the gentiles, the prostitutes, the poor, the tax-collectors, the sinners, the resident aliens, the homosexuals, or whoever was the scapegoat of the week, Jesus is left behind, holding the line for love and hospitality and bearing witness to a God who never never endorses our deluded quests to purge ourselves of one more enemy.

And when the tide turns on him, as it always does against those who refuse to go along with the majority’s consensus anger, and by their dissent expose it for the lie that it is, Jesus is again left behind, this time nailed to a tree, and this time revealing that God is willing to suffer the very worst that human cruelty can dish out rather than compromise with the deadly peace that we would build on the blood of all these victims.

If we still want a baby as our symbol of Advent, perhaps this year it will be one of those babies locked in Australia’s barbaric offshore detention centres. Because the baby whose birth we anticipate in this season was similarly threatened, even as a baby, by a flood of hatred and fear disguised as pious concern for national security, and that baby revealed to us the true face of God in the outcast and the persecuted.

And that baby approaches us now, as the crucified and risen one, who comes again to call us to wake up to ourselves and make sure that whenever the mob charges off, abandoning compassion and mercy, we are left behind. Stand firm then, when all the world is swept away. Hold fast, that the coming one may find us awake and steadfast in love and grace. Come, Lord Jesus, come.

2 Comments

This is such an awesome sermon Nathan! You nailed it! Thanks so much for your compassionate and intelligent preaching. I especially loved this:

“If we still want a baby as our symbol of Advent, perhaps this year it will be one of those babies locked in Australia’s barbaric offshore detention centres. Because the baby whose birth we anticipate in this season was similarly threatened, even as a baby, by a flood of hatred and fear disguised as pious concern for national security, and that baby revealed to us the true face of God in the outcast and the persecuted.”

Thanks again Nathan for another brilliant sermon & removing the veil of the prettiness of Christmas.