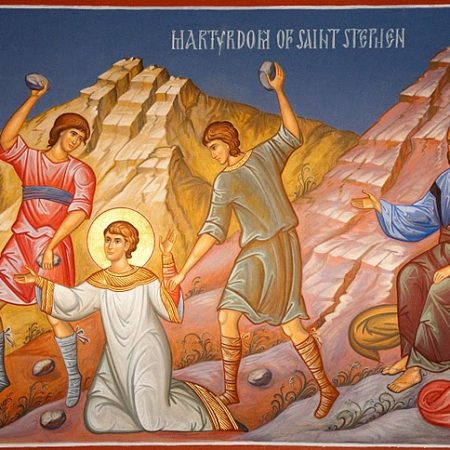

A sermon on Acts 7: 55-60 by Nathan Nettleton

The story we heard tonight of Stephen being stoned to death is often introduced as the story of the first Christian martyr. For centuries, the idea of martyrdom held a honoured place in Christian thinking. Foxe’s Book of Martyrs has been in print for over 450 years, and generations of young Christians grew up on its stories of heroic Christians who were killed because their endeavours to follow in the footsteps of Jesus provoked violent hostility.

But words can begin to convey different meanings when circumstances change, and in today’s world, the word “martyr” can conjure up very different images. The concept has been co-opted by violent religious extremists who claim to be martyrs if they die in the process of inflicting terror and carnage on those who don’t share their violent ideology. Today’s so-called martyrs are not people you want to be anywhere near, because they may be wearing backpacks full of explosives and be ready to blow themselves up in a crowded public place in an attempt to kill as many unsuspecting bystanders as possible.

So, from our perspective in today’s world, what are we to make of the story of the death by lynching of Stephen? And are we still willing to use the word “martyr” to describe him?

Let me begin with the question of language. The word “martyr” comes into our language straight from New Testament Greek, but in the New Testament it didn’t actually mean someone who was killed. It is simply the Greek word for a witness. “Your honour, I call the next martyr for the defence to take the stand and swear to tell the truth and nothing but the truth.”

So when the meaning and usage of the word evolved to speak of those who were killed for their faith, the emphasis of the word fell not on their death, but on the way they bore witness to the love and mercy of Jesus the Christ. And as the idea of being killed for that witness became more and more a part of the meaning of the word, the emphasis fell on the nature of their death as one that bears witness to the manner and meaning of the death of Jesus.

The New Testament contains three major stories of people being scapegoated and unjustly killed. The central one is, of course, Jesus himself. The other two are John the Baptiser, and Stephen the Deacon, of whom we heard tonight. When we compare and contrast the three, some important things come to light.

The Apostle Luke, who wrote down the story of the death of Stephen, deliberately highlights a number of similarities between this death and the death of Jesus. But the death of John the Baptiser is the odd one out. Although the story is still told, the death of John has not nearly as often been held up as a wonderful and inspiring example of great and courageous faith. For reasons that we perhaps can’t easily identify, it doesn’t inspire the same reverence in us. I think there is actually a good reason for that. It is the odd one out, in several important ways.

Jesus was killed because he exposed the hypocrisy of traditional religion with its rigid moral codes and its sharp divisions of righteous and unrighteous, and he bore witness instead to a God whose love and mercy flood generously over every boundary of race, creed, nationality, gender, sexuality, or morality. John, on the other hand, got himself caught up in a moral slanging match with Herod. He got himself all outraged over Herod’s sexual immorality, and it is precisely that that led to his death. John lived and died breathing fire against his “enemy”.

Now John’s behaviour is no surprise. His understandings of moral righteousness and its religious importance were well established and thoroughly mainstream. And he stood in a long line of zealous Jews who had died calling down curses on the heads of their unrighteous persecutors and promising that God would violently avenge their blood a hundredfold. So I am certainly not suggesting that John was an aberration who stands out from the crowd.

Quite the opposite, in fact. It is precisely because the death of John is so typical and even unremarkable, that the deaths of Jesus and Stephen more obviously break the mould and mark the beginning of something quite new.

Luke the gospel writer parallels the deaths of Jesus and Stephen in numerous ways, but I’m just going to focus on two of the most important ones. Firstly, both of them die praying for the forgiveness of their own murderers. “Father, forgive them for they don’t know what they are doing,” says Jesus. And Stephen knelt down and cried out in a loud voice, “Lord, do not hold this sin against them,” and when he had said this, he died.

What a striking contrast to the glaring and fire-breathing of John and the zealots who went before him who most definitely did want this and all their persecutors sins held against them and punished mercilessly for all eternity.

But I want to give a bit more attention to a second parallel, not because it is more important because it probably isn’t, but because I think it helps us to understand the meaning and importance of this forgiveness.

The thing that seals Stephen’s fate is the unflinching honesty of his speech when he is dragged before the Council. He gives a long summary of the religious history of Israel, which climaxes with his conclusion that the religious leaders of the nation have always missed the point of what God wanted and opposed and killed the true prophets who saw and announced what God was doing, and that they have done it again with Jesus.

Luke has described a speech like this before. Back in chapter 11, Jesus said, “Woe to you teachers of the Law! You load people up with impossible moral expectations, but you yourselves won’t lift a finger to help them. Woe to you! You approve of what your ancestors did; they murdered the prophets, and you build their tombs. God sent you prophets and messengers, and you killed and persecuted them all, from A to Z, from the murder of Abel to the murder of Zechariah, who was killed between the altar and the Holy Place.”

This, of course, is the truth that can’t be tolerated. Traditional morality religion must always defend the rightness of its judgements and it punishments. After all, the ability to accurately identify who are the good people and who are the ones who are a threat to all that is good is fundamental to such religion. Those who have suffered and died must be seen to be the guilty ones. We cannot tolerate someone exposing the possibility that our religious moral codes and the will of God might be on entirely different tracks. Such a voice must be silenced.

It is precisely at the end of that speech that Luke tells us that the religious leaders and lawyers began to criticise Jesus bitterly and to lay traps for him to catch him saying something wrong for which they could convict him. When we get to Stephen, there is even a sign that the mob recognise the truth that they cannot face, for Luke tells us that they have to cover their ears to block out Stephen’s words. Such a truth must be shut out. Such a voice must be silenced.

And so it is that with both Jesus and Stephen, traditional religion’s desperate need to silence their voices ensures that the pattern they have exposed fires up and repeats itself again, lynching another true prophet, and another; lynching even the most perfect embodiment of God’s generous love and mercy who dies tortured but still praying for the forgiveness of his persecutors.

That generous loving forgiveness, even in the face of a violent death, is the ultimate revelation of the truth of their speeches. Does God desire fierce moral crusaders who die angrily pointing the finger at Herod’s sexual misdemeanours, or does God desire a love and mercy that will always welcome the prodigals home and love the enemies and pour out forgiveness even as the nails are hammered in or the rocks rain down?

Deep in our guts we know the answer to that question, and that’s why the deaths of Jesus and Stephen inspire awe and hope in us, while the death of John the Baptiser leaves us feeling so much less so.

It is also why we know, deep in our guts even if we don’t know how to put it into words, that suicide bombers and poofter bashers and the whole gamut of hostile, hate-fuelled extremists who seek to impose their creed and their moral code on the world by violent means are not martyrs at all. Why?

Because even if they die for their cause, they are not bearing witness to the truth of the God who is all suffering love. Instead they have become part of the same angry mob that again and again tries to block its ears, to re-conceal the truth, and to re-sanctify extreme violence as an expression of the holy will of God. Its a horrible blasphemous lie, and ever since Jesus unmasked it, it can only be maintained by jamming our hands even harder over our ears and screaming even louder and cranking up the barbarity of the violence to ever greater extremes in an obscene attempt to make it appear god-like in scale.

But of course, it is very easy for mild-mannered, polite society, us to point the finger in judgement at these violent others who we could never imagine ourselves among. But as is often said, all that is needed for evil to go on flourishing is for good people to do nothing. It is in Luke’s description of the death of Stephen that we first meet Saul, who was later to become the Apostle Paul. And although Saul is not described as casting a stone himself, we are told that he watches on and that he approved of the killing.

The only way to avoid being swept up in the power of the mob is unblock our ears and actively position ourselves alongside the victims. For it is there that we will find Jesus, and it is there with Jesus that we will find the truth of God and the power of unquenchable mercy, the only power that can heal our hostile divided world and set us free to live in love and peace.

One Comment

This sheds new light for me. I have always cringed at the term martyrdom, especially with its contemporary usage. But this opens up a whole new awareness. Thank you.