A sermon on Romans 8:14-17 for Trinity Sunday

by the Revd Principal Paul Fiddes

Emeritus Principal of Regents Park College, Oxford, UK

A video recording of the whole service, including this sermon, is available here.

In the Church Calendar, today is celebrated as ‘Trinity Sunday’, and this poses a real challenge to any preacher. What can one say in a few minutes about the ancient and difficult formula that God is ‘one divine essence and three persons?’

It took the Church three hundred years to develop that form of words, and it has taken 1700 more to try to understand it. Many people are frankly baffled by what seems the ultimate piece of Christian jargon.

What then can a preacher say in a few minutes? Preachers try, of course. Let me briefly tell you about two sermons I’ve heard on this day in the past. In the first, the preacher invited the children who were present to put up their hands if they had three names, and asked them to tell him what they were: for example, Fiona Susan Smith. God, he then informed them, is also a person who has three names – Father Son Spirit.

The second sermon invited the congregation to think of the persons of the Trinity as different members of a football team: there’s- the manager (the Father), the player (the Son) and the coach (the Spirit) – but one team.

I wonder if you can spot the problems with these two illustrations of the Trinity?

The first – a God with three names – certainly stresses the nature of God as one, but fails to take seriously the three persons; the second – a divine team – evidently stresses the three persons but at the expense of the one God.

These hapless preachers failed to notice that they were urging ideas that the early church had long ago dismissed as heresies.

Perhaps, however, these examples have only served to confirm your belief that the doctrine of the Trinity is a highly complicated piece of jargon, little to do with everyday experience, best avoided by sensible preachers – and by congregations.

You may have some sympathy with one church-goer taking part in a recent sociological survey, who was asked what he thought about the Trinity. He replied:

“If God was 2 persons he’d be less than what he is, and if 4 persons, more than necessary. But if God decides to make another person, it’s all right with me.” That was a Baptist, by the way. He seemed to regard the doctrine as a mathematical puzzle, in which either 3 or 4 into one will go, as long as it’s God’s way of doing numbers.

But I want to say that far from being jargon remote from life, and far from being a mathematical puzzle, however holy, this doctrine actually arose from experience. First, it is

1. An experience of relationship

The technical language of the Trinity – one being, three persons—comes from the philosophy of the fourth century. But the church developed the concepts in order to understand an experience which began with an encounter with God in and through Jesus during his earthly life. It was an experience which was continued in their meeting with the risen Christ in worship, and with the coming of the energy of the Spirit on the day called Pentecost.

If the ideas seem complicated this was because thoughtful Christian believers found their experience of God to be complex. They found that the richness and depth of this meeting couldn’t be satisfied by simply saying the word ‘God’ alone; these early Christians found they had to say that they encountered the one and only Lord as Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

God’s unveiling of God’s own self was bursting the boundaries of everyday speech, and people were being called to voyage into strange regions of thought for which they only developed theological terms later on.

So in quite early days of the church, we find the Apostle Paul writing as in our text.

The Spirit we have received…. makes us children of God, enabling us to cry “Abba! Father!”

When he thought about his experience of God, he could only say that it was like a Holy Spirit helping him to call God ‘father’ because Christ had made it possible for him to become a son like himself.

A phrase from the Letter to the Ephesians also sums up the pattern of prayer as speaking to the Father, through the Son and in the Holy Spirit (2:18). To say that the One Lord whom they met was Father, Son and Holy Spirit was a symbolic way of speaking about a God who is rich in loving relationships within God’s self, and who desires to relate to us in a generous way.

Indeed, after grappling with the mysteries of the being of God, St Augustine could only sigh and confess that ‘to avoid remaining silent, we say that the names, Father and Son …. refer to the relationship’.

God, as the supreme Reality is relational.And this is what we would expect from the creator of a universe that we now know to be a network of relationships, a web holding together life at every level.

So, second, it is

2. Sharing in the life of God

God lives in fellowship within God’s self, and opens up that communion to draw us in, to include us within the festivity of divine life; the triune God makes room for us to dwell.

We have to say that all talk about God must fail. All images fall short. God isn’t like other things in the world that can be examined, or painted on canvas, etched in glass or sculpted in stone.

Talk of God as three relationships makes little sense as a way of visualising God, but it’s deeply meaningful as a way of talking about our sharing in the life of God.

Speaking of God as triune isn’t the language of a spectator but a participant; we’re not saying: “so that’s what God looks like”! We’re saying: “this is what it’s like to get involved in a network of relationships.”

One person in Christian history who tells us what this is like is St John of the Cross. He writes in his poems about an experience that he calls the ‘dark night’, when he felt alone, forsaken and without human support.

We may feel some familiarity with his state of mind at the moment, as we are separated in lock-down from our usual meetings with others, or isolated from our parents, or children or grandchildren. We may have know the darkest night of loss of loved ones, and have been shut out from being with them in their dark hour.

What St John tells us is that it felt for him like wading into deep water in the depths of night, and yet at that very moment feeling a flow surrounding him like three different currents of water, interweaving with each other. He felt, not overwhelmed, but embraced, refreshed by living water. So he writes:

The spring that brims and ripples oh I know

in dark of night.Waters that flow forever and a day

through a lost country – oh I know the way

in dark of night ….Bounty of waters flooding from this well

Invigorates all earth, high heaven, and hell

in dark of night….Two merging currents of the living spring –

from these a third, no less astonishing

in dark of night….

The poet felt, not overwhelmed by these currents, but embraced, held, refreshed as if by living water. It’s best then to avoid pictures that attempt to illustrate God, and to think instead about actual situations in which we participate in God, in which we experience, like St John, the flowing around us of supportive love.

If we do this we discover a movement which is like the movement of a son towards a Father. In the words of our text, when we pray to God as Father, we are leaning upon a movement of speech that is already there ahead of us, crying ‘Father’; we are sharing in a conversation that we can only say is like that between a Son and a Father.

Our weak word, ‘Father’, is surrounded and supported by the strong word of the Son.

Our feeble ‘Yes’ to the Father is held within his ‘Yes’ – the yes that Christ said in the wilderness, in the garden of Gethsemane and on the cross, the yes that he goes on saying in eternity. In that human and divine yes we pray. This is what it means to pray through the Son to the Father.

Paul affirms that ‘all the promises of God find their Yes in Christ; that is why we utter the Amen through him to the glory of the Father’ (2 Cor.1:20).

In our prayers in this service we have an opportunity to say “Yes” to the goodness of God; as we come with problems, troubles, sorrows, grievances, perplexities; we cannot say that “Yes” unless we lean upon a “Yes” movement that is already there, the open response of the Son to the Father. Prayer is to the Father, through the Son.

So we also find a movement of relation which is like that from a Father to a Son. It is, third…

3. Sharing in the mission of God

The Trinitarian doctrine says that the Father ‘eternally begets the Son’; that is, he eternally sends out the Son, a journey that will lead him finally into the far country, into our world to reconcile us, to call us into his own communion. We are invited to share in this movement too that is already going on:

Jesus reminds us of this at the end of this Fourth Gospel: as he breathes out the Spirit on his followers he says: ‘As the Father has sent me, so I am sending you’ (John 20:21).

So we shall find ourselves within a flow of being sent: sent to share someone’s loneliness; sent to give time and effort to help another although we are hard pressed; sent to listen to someone whom everyone is ignoring; sent to be the first to say the word of apology which will break the deadlock; sent to offer the word of forgiveness that will heal wounds; sent to speak a word of truth to power……

At this moment our physical travel is limited in the UK, even if lock-down is gradually being lifted; but we can share in this movement of being sent through using social networks, through the telephone, through letters. We can take the first move of approach to another, even at a social distance of two metres.

And as we share in these movements of the Father and the Son we find that they are being opened up to new depths of love, and to a new future of hope, by a third movement. They are broken open by a surge of energy that is like wind blowing, or breath stirring, or fire burning, or wings beating and lifting us in the air.

We can only say – this is in the Spirit.

These three movements in God are all to do with giving and receiving in relationship, so they cannot be confined to one gender.

I have so far been using the language that Christ taught us – Father, Son and Spirit: but this is not enough, never enough. These patterns of life and love can be gendered differently; they must be if they reflect actual experience.

Experience compels us to say at times we feel that these relations are also like those between a mother and a daughter, or a son and a mother, or a daughter and a father. With the Lady Julian we are compelled to say: God, our Mother.

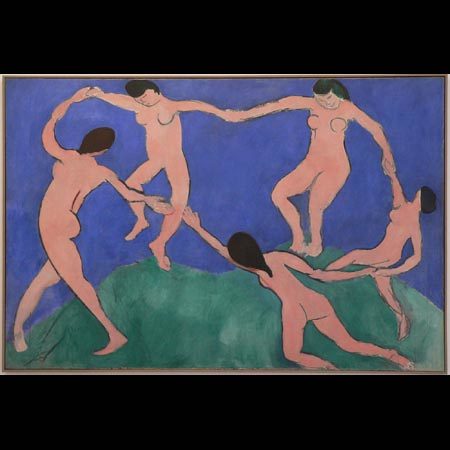

Early theologians thought of the three patterns of love in God as interweaving and intertwining with each other, entering into each other, moving in and and out of each other, living in and through each other, responding to each other.

With some more recent theologians we can think of this interactive movement as being like a dance: This is what Trinity is about: an eternal dance of love which draws us in, inviting us to join our faltering footsteps with the flow of life that sweeps on and before and beyond us. [None are locked out, none are left out.] We are called deeper into its movements, always farther out and farther in:

The dance goes on.

4 Comments

What an honour it was to have Paul Fiddes preaching for us. His book on the Trinity – Participating in God – is one of the best, and he did an amazing job of giving us the guts of it in under 20 minutes!

Thank you Paul for explaining the Trinity is such practical terms.

“These patterns of life and love can be gendered differently; they must be if they reflect actual experience.” I really appreciated this point and the sermon as a whole. Thank you Paul.

I regret that I missed this when it was presented in person. However, I’m glad to have the text here for reflection at leisure. Thank you Paul.