A sermon on Matthew 18:15-20; Romans 13:8-14 & Exodus 12:1-14 by Nathan Nettleton

One of the main charges that led to the execution of Jesus of Nazareth was lawlessness. He was accused of breaking the law himself, and of spreading teachings that undermined general respect for the law and thus increased the risk of lawbreaking by others. On these charges, I think it would be fair to say that Jesus was guilty as charged. He did break a number of the laws of his day, and he did teach other people to regard the law as being of very little importance as a guide to how they should behave.

It is rather surprising then that the Christian Church has come to be known as one of the most strident advocates of a rigorous and conservative obedience to the law, and the closest supporter of the work of state law enforcement bodies in punishing those who break the law. Just listen to how many of the vocal opponents of same-sex marriage are motivated by a rigid reading of biblical law.

There are all sorts of questions of law and obedience and discipline swirling around in the Bible readings we heard read tonight, and I think they both shed some light on how this strange paradox came about, and on how we are called to live in light of it.

The words of Jesus that we heard from Matthew’s account of the gospel have come to be known as a classic text of “church discipline”. If someone has offended, go and raise the matter with the person alone, and if that does’t work, go with one or two others, and only if they still don’t face up to their wrong, take the matter to the whole church.

These words have been used over and over as a model for an in-house judicial procedure for dealing with those whose behaviour breaches the rules and expectations of the church community. At times, keeping things in-house has been used as an excuse for cover-ups, and we’ve deservedly been condemned for that in places like the recent royal commission, but what is mostly taken for granted is that this teaching of Jesus is intended to provide a model for structuring the practices of discipline and dealing with offenders.

There is, however, a problem with this that sits there like an unexploded bomb in the middle of the passage. What does Jesus say to do with the person if they still don’t repent at the end of the process? “Let such a one be to you as a Gentile and a tax collector.” And who is this saying this? Jesus. And how does Jesus behave towards gentiles and tax collectors? He welcomes them and befriends them and parties with them and gets himself into all manner of trouble for being far to buddy-buddy with them. “Let such a one be to you as a Gentile and a tax collector.” Coming from Jesus, if that is a recipe for church disciplinary procedures, they are not going to have much in common with the structures of punishment that we are used to. So there we have a big clue to Jesus’s attitude to law and discipline and perhaps a good example of why his teachings were seen as undermining the principles of law and order.

Perhaps where we’ve got ourselves mixed up with this text is that we have read it through the lens of a pre-Christian view of God and so we have seen it as being roughly analogous to the events that reach their climax in the story we heard tonight from the book of Exodus. Now we’ve jumped over a whole lot of material in the Sunday readings, but if you have been doing the daily readings or you are familiar with the story, you will know that Moses has been ramping up the pressure on Pharaoh by bringing progressively bigger and bigger disasters down on the nation of Egypt in order to persuade him to release the Hebrew slaves.

Now this is exactly the sort of law and order that we understand. This is normal human practice. If we want to bring about a change of policy in a foreign power, and they won’t bow to reason, then we resort to threats of force and gradually escalate the level of the force until they yield to our will. This usually works, although the current escalation of tensions between Donald Trump’s America and Kim Jong-un’s North Korea suggests that it may break down if the leaders are crazy enough.

But usually it works, and because we are always sure that we are unquestionably right, we invoke the name of God to sanction our controlled use of force to bring about justice and freedom and peace. We are God’s agents, doing God’s will, and stories like this one from Exodus are used to justify our belief that this methodology which we are employing is God’s way.

If we have unquestioningly accepted that as our worldview, as our framework for understanding what God is like, then it is no surprise that we will hear Jesus’s words about going to a sinner alone, and then with a couple of others, and then with the whole church as simply another example of this same process of escalating force. Or at least we will until we trip over the unexploded bomb in the middle.

I think the reading we heard from Paul’s letter to the Romans really sets the bomb off and perhaps gives us some hope of making sense of the pieces that remain after the explosion. Paul does two things here. Firstly he completely puts the law in its place by saying that if we love one another, we will already be fulfilling the law and therefore we can pretty much forget about the law. In other words, to those who have truly followed Jesus in the way of love, the law is an unnecessary irrelevance. It makes it pretty hard to sustain an argument that would prohibit gay people from loving each other on the basis of the law. Love, according to Jesus and Paul, takes precedence over law.

But secondly, Paul points to some of the reasons why we deemed the law necessary in the first place. Quarrelling, jealousy, the desires of the flesh. The purpose of all human systems of law is to keep things like jealously and quarrelling and competing desires under control within safe bounds so that they do not escalate into war and bloodshed. That’s why there is such a fear of Jesus undermining the rule of law. What will keep things in check if the law is no longer respected?

The trouble with human desires is not that desire is wrong in itself, but that we humans have a universal tendency to get competitive about our desires. When we see other people desiring things, the value of those things increases in our eyes, and we begin to compete for the possession of those things. If you don’t believe me, go and sit with the children for a little while and note how often a pencil or book or toy sits there ignored by all of them until one of them picks it up, and then suddenly three of them all want that one and only that one. Some of the same-sex marriage opponents sound a bit like those children – “marriage is ours; don’t let them have it.”

So human desires almost always become competitive, and therefore create quarrels and jealousies. They turn us against one another by turning us into rivals, and we need to create systems of law to keep it all from turning ugly. And when it does turn ugly, we need a system of legalised punishment to identify offenders and take out our need for vengeance on them. It is like a big pressure relief valve that breaks the cycle, because whenever getting even is left in our hands instead of being placed in the hands of the state, the eye for an eye actually keeps escalating into a massive destructive feud that can boil for years.

But the Apostle is making the same radical step as Jesus here. If we follow Jesus in the way of love, he says, we don’t need the law. We can forget it. Why? Not because we have a new improved system of law and discipline endorsed by Jesus, but because the practice of genuine love renders law and discipline obsolete. Love does no wrong to a neighbour; therefore, love is the fulfilling of the law.

Now neither Paul nor Jesus are saying that tossing out the law will solve all our social problems and bring an end to war and violence. Both of them would, I’m sure, acknowledge that the law does in fact work to maintain some sort of social equilibrium. But what they would say is that it achieves that by force and by a willingness to write some people off, to give up on them, lock them up and throw away the key, sacrifice them from the community.

The most radical and earth-shattering thing that Jesus is saying in his proclamation of the good news is that that is not God’s way. Most of the world’s religions, including the most widespread understandings of Christianity, attribute our practices of law and punishment to God, but Jesus says “No, God is no Jekyll and Hyde. God has no interest in punishment. God’s desire is always and only for mercy and reconciliation.”

God is not offering a new improved system of law and discipline. As long as we keep casting jealous eyes on one another, we’ll need to keep resorting to some sort of system of law and punishment. But what God is on about, as seen clearly in Jesus, is doing away with the need for it. “Owe no one anything, except to love one another. Love your neighbour as yourself.”

Last week we heard Paul saying that the only thing he’d encourage anyone to compete over is showing one another love and honour. So what we have got here is a way of salvation, a way that can save us from the spiral of rivalry and violence and vengeance. And this way of salvation has nothing to do with following rules.

What it does instead, is gives us a way to stop imitating one another and thus becoming jealous of one another. It acknowledges that as human beings, we are naturally imitative, and it invites us to imitate Jesus instead. It invites us to imitate Jesus in his reckless and extravagant love for others, including for the gentiles and the tax collectors. Remember them? It invites us to imitate him in pursuing love instead of discipline; reconciliation instead of vengeance.

If we do that, then the so-called “church discipline process” described in Matthew 18 actually becomes not a process of escalating force, but of escalating invitations to reconciliation, and if it all fails at the end, it results in the offender being treated as one who is to be welcomed and accepted and loved and honoured, albeit now as a troublesome guest rather than as a member of the community.

It is no wonder that this was regarded as dangerously subversive by the authorities of Jesus’s day, and no wonder that it continues to be treated as such today. It’s no wonder that we constantly try to find justification in the teachings of Jesus for systems of law and social control and divinely sanctioned punishment. What happened to Jesus when he seriously pursued this is that he was regarded as a threat to social order and stability and since it is better that one die than that the whole nation be destroyed, he was sacrificed by his society.

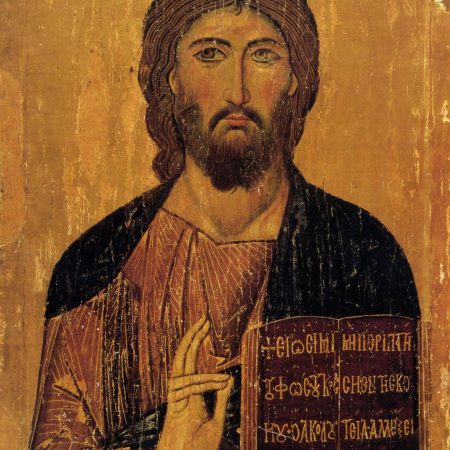

But in case there was any doubt that his radical new vision of God and of the ethos of God’s kingdom had the stamp of approval from God, God raised him from the dead on the third day, and Jesus proved, by his own actions, that even the murderous hostility of the authorities and the crowd could not make him vengeful and punitive. He stands before us still, as he will do at this table in a few minutes, reaching out to us with wounded hands, and inviting us to turn our backs on the ways of jealously and vengeful discipline, and to join him on the pathway of love and reconciliation and life.

One Comment

Thank you Nathan for sermons such as these. Gutsy & disturbing describes them well. This doesn’t mean that I don’t agree with what you are saying but will admit that I struggle with forgiveness to the unrepentant. Struggle!

We are on the same page with same sex marriage. We are all God’s children and we are made to love and be loved. Relationship open to all however we are made.

Cheers

Paul.