A sermon on Psalm 137 by Nathan Nettleton

Some preachers joke about preaching a series of sermons called “Bible passages too hot to handle.” It would tackle all those perplexing and embarrassing lines scattered throughout the Bible that we always skip over. You know, like the one where Paul says he wishes the proponents of circumcision for all would accidentally slip and knacker themselves (Gal 5:12). I’ve never heard anyone preach on that verse.

A friend of mine who is an excellent song writer used to joke about writing a new volume of Scripture in Song to cover all those same problem verses. He has penned classics which don’t quite seem to be gaining broad acceptance such as “Bring me the foreskins of ten thousand Philistines,” and one we almost heard tonight, “Dashing babies on the rocks.”

We didn’t hear that line tonight, but that’s because it is deemed too ugly to be heard in Christian worship, so the lectionary cuts the psalm short. Just one verse short. I don’t very often preach on the psalm, and even less often on the missing verses, but that’s where I’m going tonight.

Psalm 137 is frequently sung, both in churches and in mainstream music. I can remember it being a disco hit for Boney M when I was 14, and that version actually came from a Jamaican reggae band called The Melodians in 1970. “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion… They carried us away in captivity requiring of us a song… Now how shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?”

I can also remember singing another version of it in a church youth group. But I am pretty sure the last couple of verses never made it into any of the songs. They had all been cleaned up and sanitised.

Because those final verses say:

O Babylon, you devastator!

Blessed be those who pay you back

what you have done to us!

Blessed be those who take your babies

and dash them against the rocks!

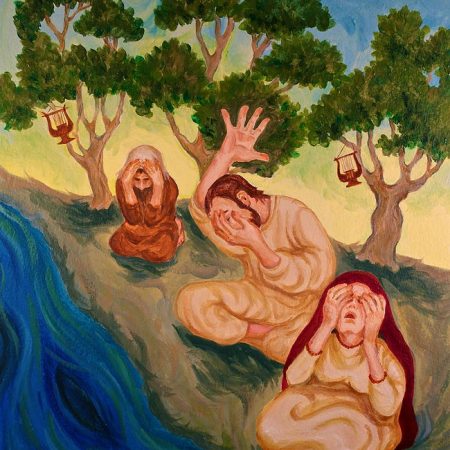

Often Christians find it very difficult to properly express grief and hurt, with our all too frequent obsession with happy victorious living. But we cope much better with the expression of grief than we do with the expression of naked rage and lust for vengeance. This psalm begins with grief, mourning and painful memory, but it ends in screaming, head smashing rage.

What are we to do with that? How do we reconcile a view of ourselves as a Bible loving people with the fact that it contains lines in which someone wishes to see Babylonian babies bashed to death against the rocks? Any way you look at it it is an ugly, vindictive and barbaric statement. It is the sort of thing that caused John Wesley to say that there are some psalms that are unfit for Christian ears. Christian people aren’t supposed to talk like that. We’re supposed to be people of patient endurance. Turn the other cheek. Love your enemies, and all that. So what do we do with this psalm and its last verse?

Let me give it a context for starters. This is one of the few psalms that clearly states its own historical context. “By the rivers of Babylon we sat down and wept as we thought of Jerusalem.” It comes from the community of Jewish people marched off into exile in Babylon after the destruction of Jerusalem in 587 BCE. It brings us the feelings and needs of a people who had been forcibly removed from their homelands under the Babylonian imperial policy of compulsory relocation, and who are clinging to their memories and their hope for an eventual homecoming.

The first three verses give us the picture. A people mourning what they have lost. Weeping by the river and hanging up their musical instruments unable to sing. Their misery was exacerbated by their overlords forcing them to sing their Zion songs as entertainment. In the same way that many of the songs of Australia’s indigenous peoples cannot be sung except in secret ceremonies, so too these Zion songs were sacred songs and to sing them as mere entertainment for people who do not share in their hope was considered pornographic.

The forced singing was intended to humiliate an already destitute people. During the second world war, the exact same thing occurred in the death camp of Treblinka. Jews were again forced by their captors to sing and dance their sacred songs as a way of stripping them of their identity, their dignity and their hope.

In the middle of the psalm it begins to move beyond grieving into stubborn resistance. “We can’t and we won’t sing the Lord’s songs in this place. May my hands whither if I fail to keep the memory of Jerusalem holy. May my tongue stick to the roof of my mouth if I defile these memories.” There is a tenacious defiance in these words. A refusal to be budged and a determination to hold on to the hope of a better future.

“You can do to me as you wish but I will not betray the vision of God’s holy city.” Jewish faith again has remarkable similarities to Australian indigenous spiritualities in its connectedness to particular pieces of land. The songs cannot be sung in the wrong place and hope centres on returning to the sacred places. Faith refuses to acknowledge that the military power of the day controls all of life. A defiant counter-attitude says that God still rules and that Babylon will meet its end.

And then the psalm begins to move into the problematic last few verses. It calls on God to hold a grudge against those who ordered the destruction of Jerusalem. And it calls blessings upon those who do unto Babylon as Babylon has done unto Israel and, most horrifyingly, upon those who smash Babylonian babies against the rocks. There is nothing noble or romantic about this prayer. It is hissing, spitting, blood curdling rage. An ugly, naked lust for vengeance that makes your flesh crawl. No wonder all the songs end it at verse six. My song-writing friend’s new scripture chorus will never catch on.

I don’t think I have ever, even for a moment wanted to see anyone’s babies smashed to death on a rock. But then again I’ve never had my children led to the gas chambers. And I’ve somehow learned to accommodate my comfortable lifestyle to the knowledge that many of my brothers and sisters cannot get enough food for their children. I was never a frightened child locked in a car outside a Casino, and I was never forced to perform sexual favours for my adult relatives. I don’t have any right to stand in judgment of such a sense of rage in such circumstances.

Some of us are old enough to remember Gough Whitlam calling for Australians to maintain their rage in 1975. That is what this psalm is – a call to maintain the rage. Take note that there is no suggestion that the original people of the psalm actually take action against anyone’s babies, or even that they would if they could. Despite the ugliness of the call for vengeance, the prayer still leaves that vengeance to God. Stark and vivid imagery is used to energise the defiance of the community. The call to remember the joys of home will not have lasting power unless it is held with a passionate anger about the crimes of the now.

At a psychological level this rage is important too. We’ve all heard it said that when anger is suppressed it poisons us slowly, usually turning into depression and draining the life out of us. There is nothing suppressed about the anger in this psalm. This vile cursing rage is brought to the altar of God, to be publicly processed, to be vented and given expression, to be worked through and offered to God for transformation into a creative energy. God would much prefer to listen to the honest pain and rage in our hearts than to the pious pretence of our sanitised niceness.

It’s ugly and awkward, but I’m glad these words are in the Bible, because if we edit out these kind of words we edit out all the hurt and anger of the abused people of the world. We edit out the people who are forcibly removed from their lands to make way for coffee plantations. We edit out the thousands of babies in Hiroshima and Nagasaki and Baghdad that our side of the wars felt quite able to incinerate. We edit out the anger and despair of those locked up without hope in our immigration detention centres. We edit out the sexually exploited women and children, the homeless, the refugees. Where will they go to express their hurt and their rage if we edit it out of our Bibles, out of our faith, out of our consciousness.

We are followers of Jesus and we are called to maintain the rage. Like the Jews in exile before us, we are a people whose first allegiance is to a world in which we do not live. Our first allegiance is to the new creation, the new world, the new Jerusalem. We are citizens of a world in which there will be no crying and no pain, a world in which the lion will lay down with the lamb, in which people will build houses and live in them, plant gardens and eat their produce; a world in which people do not have to spend years on waiting list before they can get decent housing; a world in which the economists and journalists value the life of a Sudanese or Syrian child the same as a new royal baby; a world in which schools get all the money they need and the Grand Prix corporation has to run cake stalls; a world in which people feel so thankful and fulfilled with their lives that the Casino is converted into a concert venue.

But until that vision is fulfilled, we are a people in exile. A people who mourn for what should be but isn’t. A people who refuse to cooperate with the overlords and the opinion makers and the vested interests of the present order. A people who would rather have their tongues stick to the roofs of their mouths than sanction the actions of those who measure life in dollars and culture in investment potential. A people who are enraged by the injustice and hostility and humiliation of this world and who will not be silenced until it is overcome.

We hold on to the vision of Jerusalem, the vision of life in all its fullness for everyone regardless of age, race, religion, capability, sexual identity, or immigration status, and we strive to see it fulfilled. And as a people who hold that vision of the life God has given us and called us to live to the full, we will continue to pour out vile curses whenever that life is opposed or degraded or demeaned. Those who no longer curse the enemies of life are those who no longer care.

I am not contradicting Jesus’s call to love our enemies. I am saying that our first call is to love life, and to create a world in which enemies can become friends. We love our enemies by treating them with the same justice as we are seeking for everybody else, not by acquiescing to their poisonous destructive ways.

In the holocaust museum in Israel there is a shirt made from a Torah scroll. It is a shirt which a Nazi SS officer forced an unknown Jewish tailor to make, thinking it would be a huge joke among his Nazi mates to have a shirt made from the vellum pages of the Hebrew Bible. But the joke was on him, literally. The tailor who knew Hebrew, made the shirt entirely from pages of Deuteronomy 28. You can look it up later if you wish, but it is basically a series of vile, rage-filled, wonderful healthy curses! And long may it be so.

Gutsy, gutsy sermon on a passage that most Pastors would stay well clear of. Really value the integrity & thought that goes into these sermons. The concluding remarks will stay with me as a powerful expression of non-violent rage and anger. Thank you. A beautiful spice today.

Oops… Predictive text – service, not spice – though the spices in the African peanut soup were nice too!

Thank you Nathan for your willingness (and desire?) not to “whitewash” or “sanitise” the Bible! I think that it is important that it is all used and exposed – but there are very few preachers who will (or can) do that – very often because they think that the congregation could not handle it.

We are truly a blessed community of faith to have a Pastor who is prepared to share it all with us – including the bits that others often consider “too hot to handle”. I look forward to hearing your sermon on Galatians 5:12.

Nice twist at the end to include the medley from “The Melodians”.

Thank you Nathan.