A sermon on Luke 10:25-37 by Nathan Nettleton

A video recording of the whole liturgy, including this sermon, is available here.

In last week’s very timely and thoughtful sermon, Michael Wood opened our eyes to see how the instructions Jesus gave to his disciples as he sent them out on mission called them to expect to learn of God from those to whom they were sent rather than imagining themselves as the sole bearers of truth. The next story, the famous parable of the good Samaritan which we heard tonight, has some very similar things going on.

Ironically, the hardest thing about hearing what this story has to teach us is that we think we already know what it means. The story’s very familiarity blinds us to what it is saying, and has actually changed the meaning of the key words. Nowadays, to call someone a “good Samaritan”, or even just a Samaritan, is to praise them as someone who is to be admired for their caring and compassionate actions for others in need.

But the Samaritan in this story would have had him labelled as a bad Samaritan by his own people. And all Samaritans were regarded as bad by the Jewish people to whom Jesus was speaking. They would have heard “good Samaritan” as a complete contradiction in terms, almost like saying the “good rapist” or the “good mass murderer”.

Now you probably already know that, because lefty churches like ours have been quite fond of pointing it out and revelling in the way Jesus is sticking it up the religious establishment and offending those who practice their religion in ways that create lots of boundaries around who’s pure and acceptable, and who’s not. So you will hear version like the “good asylum seeker” and the “good transsexual” to point the finger at churches that would not accept such people. But if we have the guts to really listen to it – to get past both the familiarity and the partisan take on it – we will probably find that Jesus’s confronting challenge is just as relevant to us, and just as difficult for us to swallow.

So strap yourself in, and let’s have a look at it.

First of all, the story of the good Samaritan has a context. It is told in response to a couple of questions from a religious leader, an expert in the religious law. The first question is “what must I do to inherit eternal life?”

Now, already we can easily mishear this in ways that set us off on the wrong foot with the parable that follows. In modern day popular religion, the idea of “inheriting eternal life” has come to be heard as “getting into heaven”. So the lawyer’s question is heard as “what must I do to get into heaven?” And heard like that, it sounds like a question of morality, or God-pleasing behaviour. So then we hear the parable as a simple moral lesson – follow the example of this good Samaritan and that should be enough to get you into heaven.

But “eternal life” doesn’t mean heaven. It is something that we begin living now. It is the life of God, or the life of the kingdom of God. To have eternal life means to be an insider on God’s project, to be a partner in what God is doing in the world. The lawyer speaks of “inheriting” this life of God. Inheritance was a big thing in the world of that day, and it was generally a special privilege that favoured the oldest sons. So “inheriting eternal life” is not about scraping into heaven; it is more about becoming the favoured chosen insider who fully shares in the God-enterprise, in all that God is doing. How do I get in on all that?

As you heard, Jesus turns the question back on him; “What is written in the law? What do you read there?” Pretty easy question for a religious lawyer, and sure enough, he gives the same answer that Jesus himself gave on another occasion, the answer we sang in our opening hymn: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and love your neighbour as yourself.”

“Good answer,” says Jesus. “Get on with doing that, and you’re in on the life of God.”

But the lawyer is feeling a bit like he’s being patted on the head by the Sunday school teacher here, so he asks another question, and this is where things start to get interesting. “And who exactly is my neighbour?”

It’s in response to this question that Jesus launches into the parable of the good Samaritan, but let’s just stick with the question for a minute, because we won’t properly understand the parable if we don’t properly get our heads around the question that it is answering. The concept of a neighbour was rather more complex and important in that world than it is in ours. Nowadays, outside of church, the word neighbour usually just refers to the people who live in the houses nearest to our houses.

But even if that was all it meant, you could perhaps still get the gist of the lawyer’s meaning. It would be something like “how close to my house do their houses have to be to qualify as being my neighbours? At what distance from my house are people no longer my neighbours.”

Even with that, can you see what he’s doing? It is a question of limits, of relevance. Who is relevant to this discussion, to this law, and who is not? The law says I am to love a certain group of people. Who are the relevant group of people? And of course, if we can establish who the relevant group are, we will also have established who is not relevant to our considerations, who we are exempted from having to love and care for.

This way of thinking has been written deeply into our bones by generations of social conditioning. It has shaped much of the world as we know it. Uncle Den and other Indigenous people can teach us much about the atrocities that have been committed against them and their lands because they weren’t regarded as relevant to this call to love our neighbours. Most colonisers didn’t consciously decide to inflict evil; it just never occurred to them that Indigenous people might be regarded as equals, as fully human neighbours. And if you think we’ve grown out of such thinking, try working out why so many Indigenous people are dying in police custody, or why our society locks up asylum seekers and denies them the most basic of rights. We have been schooled in a mindset that regards some people as neighbours and others as irrelevant.

We all think like this at times, but let’s see how it worked for this first century lawyer before we come back to see how it works for us in our world now.

In the ancient world, all your relationships were defined by traditional structures of social obligation, and these obligations were backed up by the threat of punishment from the gods, delivered by the religious community. These obligations went two ways; you were obligated to stand by your fellow community members and share with them if they were in need, and you were obligated to stand with your community in hostility towards all who were regarded as enemies of the community. Who you cared for and who you fought against were not your own personal choices, but community decisions and social obligations.

So you can see where the lawyer is coming from when he asks Jesus, “Who is my neighbour?” The lawyer knows perfectly well who his neighbours are, because this is a clear-cut matter of community consensus. But he knows that Jesus has a reputation for behaving in neighbourly ways towards people who are socially defined as godless outsiders and enemies, so he is hoping that he can trap Jesus into giving an answer that everybody present will instinctively react to as unthinkable, offensive, and traitorous.

The central law is not in dispute. All are agreed. “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and love your neighbour as yourself.” But who is my neighbour? Who is relevant and who is irrelevant to me, to my living out of this law, to my living as an insider of God’s life in the world?

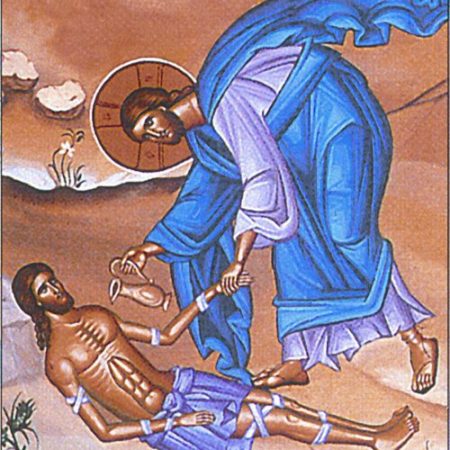

So Jesus tells this famous story, and then poses another question of his own. The story is simple enough. A man is robbed and beaten to within an inch of his life and left for dead on the side of a road between two major towns. One after the other, two respected religious people travelling down that road, see the victim, and hurry on by without stopping to help. Then a Samaritan man comes across him. Samaritans and Jews didn’t just hate each other. The social obligations dictated that they treat one another as enemies. “Giving aid and comfort to the enemy” is still a crime today. In the USA it can attract the death penalty. If this Samaritan stops and helps, he is not going to be seen as a “good” Samaritan by his own people, but as a traitor. And no Jew could see him as good, under any circumstances.

But in Jesus’s story, it is the Samaritan who stops and gives first aid, and transports the victim to the nearest place of shelter, and opens himself to being completely ripped off by writing a blank cheque to cover the costs of the victim’s care.

And then comes Jesus’s next question. “Which of these three, do you think, was a neighbour to the victim on the roadside?”

Do you see what Jesus is doing here? He has turned the lawyer’s question on its head and made it impossible to wriggle out of. If Jesus had used this story to address the question in the terms the lawyer asked it, then the question of who is the neighbour would not have been applied to the three by-passers, but to the victim. The question would have been, of all the victims I might come across on the road, which ones are my neighbours who I am socially obligated to provide aid and comfort to, and which ones are irrelevant to me and my community and can therefore be passed by and left on the side of the road?

But Jesus flips it upside down. He gives examples of three different responses to the victim, and then asks, “Which of these responses was the neighbourly one? Which of these three people behaved as a neighbour? Who put neighbourliness into practice?”

And if you remember the original context, that means that Jesus is implying a deeper question; “Which of these three showed himself to be living the life of God, to be a child of God, a beloved partner in God’s work in the world?”

This flip does two things. Firstly, it asks us who we are willing to be schooled by. This Jewish religious expert is being asked whether he is willing to see this godless Samaritan as a role model of what being an insider to the life of God looks like. That’s very similar to what Michael was pointing out to us last week about our willingness to learn of God from those to whom we thought we were going on mission.

And secondly, flipping the question doesn’t negate the first question; it expands it. Both angles now stand. Who should I regard as a neighbour, and how do I prove myself to be a neighbour?

And the answers are now linked. The first question I need to ask of myself – How do I be a neighbour? – is now tied to the other question. Whether I am a neighbour flows from who I recognise as a neighbour and whether I dismiss some potential neighbours as irrelevant. I will be a neighbour, and thereby be a partner with God’s work in the world, by breaking with the social obligations and regarding everyone else as my neighbour, as one who now has a claim on my love, care and help.

Now, in our modern world, the challenge of this is heard a bit differently, because those traditional structures of social obligation have broken down. In a secular society, who we regard as having a claim on our love has become much more a matter of personal choice rather than divine or social obligation. There are still some strong social norms and expectations. You’ll hear an example of this every time you hear a report of someone’s tragic death. The first thing that is always said to assure us of what a good person this was is that they really loved their family. And whenever there is any perceived threat to our nation, people are eulogised for loving their nation.

But such things are not the signs of the life of God that Jesus is pointing to. Loving your own family and loving your own nation fall comfortably within the socially acceptable limits of neighbourliness that the religious lawyer would have been quite comfortable with. Nearly everyone does that. It is our capacity to love not only our own, but those beyond such bounds that Jesus is pointing to and calling for.

What the breakdown of those old social obligations has done is turn two categories into three. There used to be those we were obligated to love and care for, and those we were obligated to reject and hate. In our age, where our stance towards other people is more something we choose for ourselves, there is a third category, and it is one that is probably more important to how we work out the relevance of Jesus’s words to our lives. This new third category is those who we regard as simply irrelevant to us; those to whom we are simply indifferent. As one of my favourite songwriter’s puts it “I don’t hate you, it ain’t that big a deal; You don’t even figure in the way I feel.” (Chris Smither, Lola)

Not many of us have long lists of people we regard as enemies who we’d gladly leave dying on the side of the road. But all of us have lots of people who we regard as being beyond the reach of our care. I know I do.

Often it is due to geography, and it is hard to see what I can do about it at an individual level. There are millions of people in serious need who I never pass on the side of the road, because I don’t live anywhere near them. But if I’m honest about it, the bigger challenge for me is those people who I do have access to, but for one reason or another, I have written off the relationship. These can even be people in our own families. I have several close relatives who I have almost nothing to do with. I don’t hate them, but they feel irrelevant to me. In the ancient world, social obligation would have ensured that I took care of them anyway, but nowadays it has become a personal choice, and I have chosen to largely disregard them.

But Jesus isn’t endorsing either the ancient system or the modern system. He is saying that it is the systems that are irrelevant, because the systems are about defining limits to our love, limits that Jesus wants us to overturn. Whatever the system, those who are partners in the life and mission of God are those who go way beyond the system and treat everyone as neighbours with a claim on our love and care. Whenever I wilfully write someone off as irrelevant to my life, my love, my care, I am stepping outside the life and action of God; I am making myself part of the world’s problem instead of part of God’s solution.

In the end, as all those “she really loved her family” eulogies hint, loving your neighbour, Jesus style, is not made evident by showing your devotion to your “loved ones”. The real test is who you withhold love and care from when they come within range. Who have you written off as irrelevant? Who are you indifferent to? Who are you willing to turn your back on and walk away from?

There is nothing easy about this. I know that I find it extremely challenging. My dismissal of those people I’ve written off feels entirely justified to me, but Jesus isn’t asking me to justify it. He’s asking me to change. And I don’t even know where to start. But that’s the challenge. I’m sure it is just as much of a challenge for you, and if not, it probably just means that I have failed to make the message clear here.

But for each of us who want to follow Jesus, who want to be part of God’s family, part of what God is doing in the world, that’s the challenge. Which of these three was a neighbour, was a partner in God’s loving action in the world? The one who rose above the social expectations and didn’t see anyone as irrelevant to the call to love others as God has loved us. Yep. Go and do likewise and you will be swept up into all that God is doing.

This question of Nathan’s “At what distance from my house are people no longer my neighbours.” was one that I wondered about as quite a small child – I thought that Jesus should have been a bit clearer in this matter and has been on my “pile” of unanswered questions for a long time but today I can remove it.

Thanks Nathan

Nathan certainly gave us plenty to absorb and practice in our lives. I am sure he could have given us more but he wisely kept to a time-frame rather than make a display of his obvious breadth of biblical and pastoral understandings. So therefore, like Sylvia, I will comment on what he answered for me and where he led me to think more deeply.

Nathan’s first point is the question about inheriting “eternal life” ie life without limits. I took his cue to then see that Jesus’ answer matched that phrase – “to inherit life without limit” must partner with “doing love without limits”. Hence Nathan’s teaching that the Gospel text turns around the lawyer by turning around the question – from a question about “limits” to a question about my willingness to live “beyond the limits”. Here i jump ahead beyond Nathan’s explicit sermon to some of the things he obviously left unsaid for our benefit with respect to time.

We all know that John Fowler had an accident recently such that his face and the asphalt at the church were in competition. Now the parable of the Samaritan and the “man who fell in with robbers” is a text from St Luke Chapter 10. I have always remembered that Luke’s first few verses in Chapter 1: 1-4 contain a reference to being given an “assurance” with respect to the catechesis that his friend Theophilus had received. A catechesis that we too can be assured about by reading Luke as well. Now the Greek text of Luke’s word for “assurance” is “asphaleia” from which of course we derive our modern word for “asphalt”. So obviously John’s encounter at the church with the asphalt in the carpark will henceforth make him our leading expert on the solidiity of Luke’s choice of an appropriate wording to draw Theophilus into the Faith Community. In looking at this Lukan prologue, as scholars seem to term it, there is another Greek word with some 16 letters: “peplerophoremenon”. Cutting to the chase, scholars suggest that the word refers to what it is that Luke is doing in writing his Gospel. It is to assure Theophilus that Jesus is the fulfilment of all that the Old Testament canon predicated of Yahweh. This is important since a big question at the time of Luke and the other evangelists was the impact on the Gentile converts of the application of Torah catechesis and whether Yahweh has actually achieved in Jesus what the Old Testament had prophesied of Yahweh. So when Luke delivers to us the text on Jesus response to the lawyer with the Samaritan story, we have been fore-armed right back in Chapter 1:1-4 that Luke is not writing about a Jesus who is disloyal to the Torah. In fact the Gospel is one long account of witness to Jesus as being alone in understanding Torah in its completeness..its fulfilment. As many scholars remind us: Jesus is not simply “good advice’ but Jesus is Good News. He is News because He alone takes us “back to the future” with assured teaching that is Torah based. As Nathan said- the system has become lost in its own doings rather than the doings of the Torah. Which leads us to the other startling aspect of Luke’s text – the Greek word “esplagchnisthe” = compassion but at the level of visceral responses. The word reflects the original Hebrew word for ‘mercy’ derived from the inner organs and especially a reference to the maternal instincts based around the womb/uterus. The biblical terminology for a ‘brother or sister’ in the Greek words derived from the literal description of “being someone from the same womb”. Yahweh was described in these terms….viscerally/gut level feelings…Israel belonged to and was possessed by -uniquely – by its monotheistic God – feelings engendered by “blood lines” but applicable to kin or stranger. Hence Nathan could talk about “God’s family” not limited by blood kinship alone. So when Jesus constructed his story the lawyer would have immediately recognised that Jesus was well and truly grounded in the Torah and was not just constructing a modern day “woke” question to trick him. And here in this text is why Jesus is not simply “good advice”. He is Good News. The Torah lawyer would have immediately recognised the acuteness of Jesus’ confronting juxtaposition of a worldview based upon Yahweh thinking and a worldview based upon a Samaritan acting within that worldview – immediately the Torah Jewish Lawyer would have recognised that failing to validate the Samaritan’s response was also to deny an act typical of Yahweh. So the significant thing that Luke is telling Theophilus and Us is this – Jesus is the best of Jews because not only does he know his Torah from the inside but he is completely au fait with Jewish techniques of argument, rhetoric and teaching. One of those principles was that not only did Torah hold to General Principles it also functioned at the individual level- there was an answer for every circumstance in priority to simply applying general moral principles. Hence the noticeable Lukan technique of describing the injured party in the ditch in a way that showed his innocence and therefore his right to be given assistance – he is not named but that does not mean he is “anonymous’ – Luke described him twice as a “man who fell among robbers” – this double affirmation of the man’s innocence attested that Torah required a Torah observant person to deliver the man’s entitlement – the entitlement to be rescued from the violence of the robbers. Torah preferenced this immediate need and over-reached the less proximate Torah rules about purity and such like. The Lawyer’s answer evidences this to be so. Jesus’ was not just a kind socially just person – Jesus reflected the Word of Yahweh within the rules of the lawyer’s demands. And so we should not be surprised to find that Luke’s crucifixion text has a Roman Centurion declaring that “this man is innocent/just” – terminology that the lawyer tried to apply to himself and which the parable only applied to the “man who fell among robbers” – Lukes’s biting satire that Jesus’ crucifixion also was a story of a “man who had fallen among robbers” – doubly satirical given that the Lucan text of Jesus’ Cleansing of the Temple further described the worship space as a “den for robbers”. As Nathan catechised us – Jesus life reflects what living on the “inside” of the God life looks like not just “In Principle” but in the “DOING!.