A sermon for the Paschal Vigil by Roslyn H Wright

In the readings we have heard tonight are the stories that have shaped our understanding of God and God’s action in the world since the dawn of time. From the story of the creation of the cosmos and culminating with humans created in God’s image; Noah and God’s commitment to never again flood the earth; Abraham’s commitment and God’s promise for a great nation to come form him; the exodus from Egypt of his descendants and their rescue from the pursuing army of Pharaoh; God’s promises to bring the exiled nation back to their homeland and Jerusalem; and the focus of this night – waiting for the moment when we see and know for ourselves that God has fulfilled the promise to overcome sin and death and calls us into new life with Christ. These are the great stories that we listen to, stories that shape us and invite us into greater life, truth, and freedom.

But there is a darker side to what is happening here and, at the risk of ruining your joy, I am disturbed at times by what I read in these stories. They contain images of wholesale ecological destruction, of child sacrifice, of genocide, the land occupation, the macabre restoration of flesh to bones, and the interpretation of the crucifixion as a necessary blood sacrifice to satisfy God’s anger at sin. Horror stories!

I can’t give you an answer to this paradox. It is beyond my capacity, and you have to find your own way of holding the questions they raise. What I would like to do is talk with you about my own journeying with some of the big questions in recent weeks.

At the beginning of February I started at Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre as a pastoral care intern. Cancer is a word that always carries the threat of death, of drastic treatment procedures, suffering and loss. My role is mainly with inpatients and their families, and the staff, offering pastoral care, offering spiritual and emotional support as needed. It is a challenging environment in which the processes of surgery and treatment are very visible and quite confronting. And not always successful. So we deal with those who are at the end of life, and with death. It is hard work, challenging work, and I love it. I love it because it is real! Just as an aside, I have begun to wonder if people go to church to avoid talking about the real stuff of life – much easier to get something pre-prepared by the preacher than to do your own wrestling. What I meet on the wards is people being real, wrestling with the questions of life and meaning and purpose. Not everyone is able to face this. There is a lot of denial, anger, grief. But there is also great courage, grace, truth, and love.

It is the power of love in the face of death that fascinates me. I experienced it myself when my husband Patrick was dying with cancer last year. He said he was dying in love – loving those around him, being loved. I spoke these words at his funeral:

The apostle Paul said: “Nothing can separate us from the love of God.” I have come to believe that nothing can separate us IN God’s love. I trust Patrick into that mystery that is God’s love, and I know that in God’s love our relationship continues. I carry him in my heart, and so do each of you. Patrick is not finished with us yet.

I wrote those words, and I have yet to discover what I meant. What does it mean to entertain the possibility of still being in relationship with Patrick? I don’t feel his presence, I feel his absence. How are we held together in God’s love? I talk to God, and I talk to Patrick. God is more responsive. With Patrick there is a void, a blank space, filled only by my memories that say: this is what Patrick would say, or how he would respond, if he were here. Do you call that a relationship or wishful thinking?

At our wedding I made vows that included this: ‘At the end of our life’s journey together, I will be with you.’ I was with Patrick when he died, so is that the end of the commitment? What does it mean to think that somehow he will be with me at the end of my life’s journey? Working at Peter Mac has brought my own questions about life and death to the front of my thinking. My theological and philosophical ponderings have to be grounded in my own experience. I want to be able to bring something into my care of people at Peter Mac that is real, not theoretical. I don’t want to offer set religious answers to real questions.

A couple of weeks ago I was asked to visit a man who was in palliative care. Only in his 40’s, he was reduced to skin and bones, with dis-coloured skin, wearing an incontinence pad. But his eyes were bright and lively. He didn’t mess around with small talk – ‘I’m up against it’, he said. ‘I’m agnostic, but I want your take on it. Tell me what’s out there.’ This was an amazing moment for me, very precious, and sacred. I took a deep breath, and told him I don’t know, it’s a mystery. But I have hope that there is something more. He had a sense of that too, but no words to put to it. I suggested that love was the power holding the cosmos, and he came alive. He knew love, love for his 12 year old daughter, love for his wife, love for his 19 year old son with whom he had a difficult relationship. He wanted a way to convey this to them, and I suggested writing a letter. He realised that this was a way of them being able to experience his love after his death, reading his words, hearing his voice through the words, feeling again the love he carries for them.

Love in the face of death. That love enabled him to reach out to his family with courage and dignity. It gave them all the capacity to share, to acknowledge their relationships, to affirm and build these relationships. And it enabled this dying man the freedom to let go, trusting them to the power of love.

Viktor Frankl was a therapist who was interred is a concentration camp during the Second World War. He told how a scrap of paper was found in the hand of woman who committed suicide that said, ‘More powerful than fate is the courage that bears it.’ The words on their own were not enough to save her, she needed something more. (Victor E. Frankl, The Will to Meaning: Foundations and Applications of Logotherapy New York: Plume Book, 1969, pp.7-8.)

But they are strong words that speak to me. ‘More powerful than fate is the courage that bears it.’ I see every day the hard hand that fate has dealt people. And I see the courage that bears it. And something more. Frankl developed a psychological theory that named the need for human existence to transcend itself, to find meaning outside ourselves. And he knew the value of relationships. He wrote, ‘One has long ago come to realize that what matters in therapy is not techniques but rather the human relations between doctor and patient, or the personal and existential encounter.’ (ibid., p.6.)

We find our meaning, a reason for existence in person-to-person encounter, in relationships, in love. We are each unique, and each one of us is irreplaceable. You may be replaceable in the things you do. But you are irreplaceable in your relationships. Only you can be you in the network of relationships that surround you. No one else can be who you are to those you love, to those who love you. In your loving you are unique.

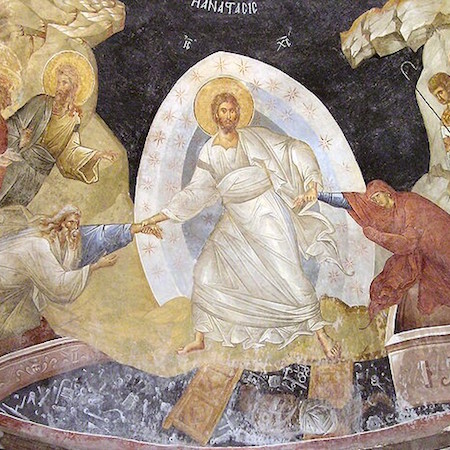

What has any of this to do with the celebration of Easter, with the resurrection of Jesus? Life and love in the face of death and destruction. That is why we are here tonight. Jesus was brutally executed. He died, and in that moment died the hopes of those who followed him. They had encountered in him a man of courage and truth, a man of freedom and integrity. But he died and they were bereft. But something happened that brought them hope again, that enabled them to look beyond themselves and find meaning and purpose that has resonated down the millennia to us here tonight, and to millions of people around this planet.

Don’t ask me about the literality of the resurrection – I can’t answer that. But something happened, something extra-ordinary that turned their fear into a great force that flowed out and changed the world. They experienced new life, new possibilities, new love. Death had taken so much from them, but death was not the end of their relationship with Jesus. They were touched by his life and his love and empowered to be more. They found a new life, new freedom, new meaning. These people were met by Jesus. The encounters that had with him changed them. They found life in Jesus. Jesus was alive in them. And in us.

In my pondering of the question of relationships and death, I was on my way to work one day, listening to some music as I walked up Collins Street. The words of the song suddenly threw up an image and experience of God’s love that caught me by surprise. I saw Patrick’s face, but watery, dissolving, and behind it, or through it, I had the sense was the face of God. I came to a realisation that Patrick’s love for me was God’s love for me, and that continues. The separation between Patrick and God in my mind now seemed somehow artificial, and is dissolving. All loving is God at work. It was reinforced the same day on the way home in the train when I saw a man looking at his partner when she staring out the window, and his face softened with love and affection that was palpable to me. And again I thought, all loving is God at work.

That changes my need (for the moment, at least, I’ll admit) to find a sense of connection with Patrick. He is held in God’s love, and God’s love holds me. It changes what I think I am doing in the hospital too. I want to affirm love wherever I see it, however it is expressed. I want to bring real human contact to every encounter, to affirm the value of this life, this person, this story. I want to help people be real, speak the truth of their experience, and find freedom and courage, life and love, in the face of death, diminishment and destruction. Death is not the end of love, and something new awaits us.

The resurrection awaits us. It awaits us now as we live into our experience of the love of God, growing in us and through us. The resurrection awaits us too, that moment when life as we know it is no more, and we enter fully into the life and love of God.

I began by talking about the Great Story of God’s action. I want to finish by affirming the value of each and every small story, your story and my story. The story of our loving and our living, sharing and growing God’s love and God’s action in our world.

Christ our life, you are alive, in the beauty of the earth,

in the rhythm of the seasons, in the mystery of time and space. Alleluia

Christ our life, you are alive, in the tenderness of touch,

in the heartbeat of intimacy, in the insights of solitude. Alleluia

Christ our life, you are alive, in the creative possibility of the dullest conversation,

of the dreariest task, the most threatening event. Alleluia

Christ our life, you are alive to offer re-creation to every unhealed hurt,

to every deadened place, to every damaged heart. Alleluia

You set before us a great choice.

(Hannah Ward and Jennifer Wild, eds., Resources for Preaching and Worship – Year C: Quotations, Meditations, Poetry and Prayers, Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2003, p.136.)