A sermon on Isaiah 6: 1-13; 1 Corinthians 15: 1-11 & Luke 5: 1-11 by Nathan Nettleton

A video recording of the whole liturgy, including this sermon, is available here.

Most of the time we don’t expect anything too dramatic to happen in our worship service. Sure, our worship service here is a bit more intentionally dramatic than some, but we don’t usually expect anything really outrageous like people falling on their faces and screaming and thinking they are going to die, or anything like that. And if it did happen, our first reaction would probably be to think it was an attack of some kind of illness rather than an epiphany, a glimpse of the reality of God.

All three of tonight’s readings refer, either directly or indirectly, to epiphanies where the one who glimpsed the reality of God was knocked flat by it and scared out of their wits.

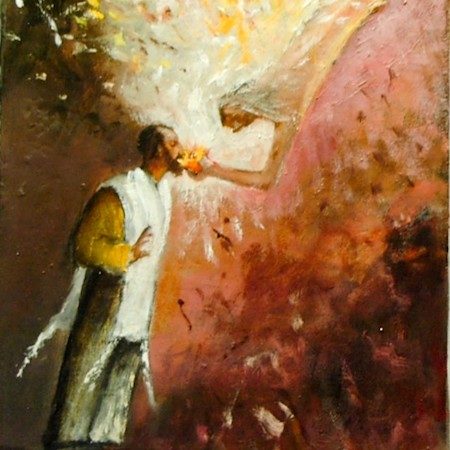

The first of these, Isaiah’s vision in the temple, probably does happen in the context of a worship event. The temple is filled with incense smoke and the “Holy! Holy! Holy!” hymn is being sung and suddenly Isaiah is not just seeing the priests and his fellow worshippers but the throne room of heaven. What an epiphany! The Lord is sitting on the throne, high and lifted up, and the seraphim are winging their way around him and singing, and Isaiah falls on his face and thinks he is going to die. “Woe is me. I’m done for. I’m a sinful man from a sinful race and I’ve stumbled into the very throne room of heaven.”

The scene in the reading from Luke’s gospel looks quite different, but the impact on Simon Peter is similar. It is not set in a temple or synagogue, but there is a crowd of people gathered to hear Jesus preaching, so it is not completely without liturgical context. But after the sermon, Jesus, a carpenter turned preacher, tells the fishermen how to catch fish, and somewhere in that interaction, Simon Peter catches a glimpse of who Jesus really is. Suddenly he’s not just seeing the Jesus who is seated in the bow of his boat, but the Jesus high and lifted up in the throne room of heaven where the seraphim sing “Holy! Holy! Holy!” And when Simon Peter saw that, he fell down at Jesus’ knees, saying, “Go away from me, Lord, for I am a sinful man!”

Our other reading, from Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, was mostly taken up with a kind of creed, a statement of faith in the crucified and risen messiah, Jesus. But at the conclusion of the creed, with its list of people who were eye witnesses of the risen Christ, Paul adds a personal reference to his own encounter with the risen Lord. “Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared also to me. For I am the least of the apostles, unfit to be called an apostle, because I persecuted the church of God.”

Can you hear the same note in that? “Go away from me, Lord, for I am a sinful man!” Paul is knocked off his horse on the Damascus road, and the piercing light of God shines around him and he is suddenly painfully aware that he is a persecutor of God’s church, a sinner of the first degree. “Woe is me. I’m done for. I’m a sinful man from a sinful race and I’ve stumbled into the very throne room of heaven.”

As I reflected on these three stories, I was struck by a question. These three characters are all, at first, paralysed by their epiphanies. They catch a glimpse of the reality of God, and they are knocked flat and frozen to the spot. They think they are done for; that there is no hope for them. Confronted with all that God is, they see themselves for all that they aren’t and they abandon hope. “I’m done for, for I have stumbled into the very throne room of heaven.”

And as I thought about that, I realised that I know lots of people who are similarly paralysed by a sense of their own worthlessness. I know people whose every encounter with any expression of goodness and love and generosity seems only to reinforce their condemnation of themselves, deepening their sense of their own corruption and lovelessness and selfishness. They are constantly falling down, appalled at their own baseness, and crying “Stay away from me, I am not worthy. I am not worthy.”

But there is a very big difference, isn’t there? Because despite these stories, what we remember Isaiah, Simon Peter, and Paul for is not their paralysis, but the way they were set free to become astonishing people of action and integrity and courage.

Isaiah is commissioned right there in the midst of his epiphany to become the courageous prophet who proclaims the just demands of God in the face of the corrupt power brokers of the political and religious establishment. Simon Peter leaves his nets and becomes one of the leading Apostles, the one upon whom Jesus described his church as being built. And Paul becomes the Apostle to the nations, second in importance only to Jesus in the birth and spread of the infant church.

So what makes the difference? That’s what I’ve been pondering. What makes the difference between the epiphany that convicts someone of their sin in a transformative way that lifts them to their feet and sets them on fire for the gospel, and the despairing plunge into one’s own sinfulness that paralyses us and leaves us with our faces in the dirt?

What makes the difference?

As I wrestled with that question, I began to wonder whether the way the churches have preached the gospel is perhaps part of the problem. Perhaps we have been so eager to reproduce the experience of Isaiah and Peter and Paul that we have tried to push people into that experience of confrontation with their own sin. We have proclaimed “sin, sin, sin” and “repent, repent, repent”, but in the process, we have laid a trap for our own feet. A focus on sin has led not to freedom, but to a sticky bog that drags us down and befouls us. We become horribly conscious of our corruption, but can see no way clear of it.

Isaiah and Peter and Paul did not begin with a vision of sin, but with an epiphany, a vision of God. They saw not sin, but glorious righteousness and justice and love and generosity. They saw a vision not of what they were, but of what they were created to be and called to be. The awareness of failure came from the vision of its opposite, from the vision of what they could become.

And so I wonder whether our evangelical focus on sin and repentance has left us kidding ourselves and those to whom we minister that we have been truly saved if we have become sorry for our sin. Because the terrible truth is that the world is full of people who are sorry for their sin and failure and corruption, but they are still trapped in it with their faces in the dirt saying “I am not worthy, I am not worthy” but with no sense at all of how to break free and move beyond that.

Salvation comes, not in the conviction of sin, but in the encounter with grace. The true epiphany gives us a vision of the Christ who reaches out his wounded hands to welcome and embrace us in extravagant mercy. That might make us painfully aware that we were in the crowd that bayed for his blood, but the thing that overwhelms us is grace, reckless love and acceptance. A love and acceptance that reaches out to us even before we look for it or perhaps even before we realise we need it.

That’s why, in our liturgy, we declare everyone’s sins forgiven; each and every person one at a time, without any regard for where each person might be on the journey to faith and acceptance of God’s mercy. For God’s mercy in Jesus always goes before our response. Your sins are forgiven, whoever you are and whatever sins they are. Your sins are forgiven, but that won’t set you free unless you accept it and embrace it and rise to your feet in the experience of it. There are no sins that God’s mercy cannot reach, and no people who are excluded from God’s offer of love and grace.

Did you notice how Isaiah said not just “I am a sinful man,” but also, “and I live among a sinful people”? The encounter with grace didn’t make him feel more sinful than everyone else. It made him conscious that he was just like everyone else; that all had sinned and fallen way short, and that all alike stood in need of the fiery love and mercy that he had just stumbled into. It makes us aware that we are rightly nicknamed “SYCBaps”, for we are indeed as sick as everyone else, and perhaps more aware of it than most, but we have discovered that it is the sick to whom the physician comes with healing hands to lift us up and set us free.

We are a forgiven people. The stain of corruption that had blackened our souls came to light even as the seraph touched our lips with the burning coal and spoke the words of pardon to us: “your guilt has departed and your sin is blotted out.” So let us affirm our faith in song, and then approach again the table of epiphany, the table where we see the broken one, the crucified and risen one, high and lifted up and burning with the love that raises us to our feet and opens our lips to join in the cries of “Holy! Holy! Holy!” and sets us free to go out and change the world with the burning love of God.

Nathan’s commanding sermon leaves little room additional comment to match his teaching. I found what he had to say really profound: “………….Isaiah and Peter and Paul did not begin with a vision of sin, but with an epiphany, a vision of God. They saw not sin, but glorious righteousness and justice and love and generosity. They saw a vision not of what they were, but of what they were created to be and called to be. The awareness of failure came from the vision of its opposite, from the vision of what they could become.

I found his repeated use of the phrase – “I’m done for, for I have stumbled into the very throne room of heaven.” – markedly relevant and a source for a great prayer text.

We use the Isaiah text ( Holy Holy Holy etc) in the Sunday Service Liturgy. In the Catholic Mass the text is situated in a central part of the liturgy – The Eucharistic Prayer begins with a PREFACE which crescendos with this text from Isaiah. Given that Latin was the dominant prayer language of the Catholic Mass from 1570-1970. most of the Music and Poetry that emanates from this part of the Mass is known as The Sanctus. Like much Latin/Italian opera, the language lends great emotion to the musicality and poetry of the meaning. For all that though, my estimate is that 99% Catholics have “NOT had” – and continue to “NOT Have’ – any idea of the spirituality behind the words – certainly nothing anywhere near the profundity of Nathan’s teaching. Catholics have been so distracted by the next part of the Eucharistic Prayer – the so called Consecratory Prayers of the Dual Elevations of Bread and Chalice; and also distracted by the “miracle-making” belief in so-called “transubstantiation – that the spirituality brought to light by Nathan hardly touches the lived experience of the devotees of the Catholic Mass. Certainly the element of Real Presence experienced in the action of the Roman Catholic Mass does produce reactions parallel to what Nathan is speaking about. However the catholic doctrine of the Mass and transubstantiation tends to be a standalone product within any open acknowledgment of its roots in other parts of the Old and New Testament experience. It tends to gain its traction as a “miracle among miracles” rather than being experienced as the fulfilment of years of Jewish and Early Christian piety and relationship with the Holy. It also gets confused with the role of Ministerial Priesthood and Clericalism which gets in the way of a lived experience of the Corporate Priesthood of the Whole Body that a wider appreciation of Scripture cultivates.

Having painted a picture of a church monopolised by Eucharistic Piety, one shining light was that yesterday’s Sunday Liturgy was themed, for Catholics anyway, as “Word of God” Sunday. I found this curious until Nathan’s sermon made me hunger for searching behind the obvious “fish” miracle and to seek out other aspects of the Gospel text not so obvious.

What I have found, and what explains why the logo of “Word of God” Sunday is so appropriate, is the focus of the text on the Authority of God’s Word – quite apart from the miracle and even prior to the miracle. Notice that the crowd are “pressing” Jesus “in order to listen to the Word of God”. In Greek the word for “pressing” has cognate meaning with “a boat that is beached and pressing on the shore”. Jesus has the boat depart from the shore; Peter would have Jesus depart from him; finally the boat returns to shore and “they leave everything and follow”. There is a lot of ‘coming and going’ in the text. Luke’s whole gospel narrative is built around a theme of ‘journey’. Even Peter puts his boat out into the deeper water to put down his net “on the strength of your word” – as one Greek text translates the literal meaning. Peter acts prior to the catch of fish. Peter calls Jesus ‘Master’ – “epistates” in Greek rather than the usual “despotes”. An ‘epistates’ is one who carries ‘innate authority’ and is followed intrinsically. A ‘despotes’ is an absolute ruler and is followed extrinsically under direction and control. Finally the phrase “henceforth/from now on” is the same phrase that Mary uses in Luke 1(48) in her Magnificat prayer: “… from now on..all generations will count me blessed..”. Luke makes the foundation of the Visitation to Elizabeth in Mary’s response in the accompanying Magnificat prayer – which refers back to the earlier magisterially humble response of Mary to Gabriel: “..let it be done according to your Word……”. Peter’s response to Jesus sounds and affects the listener much as Mary’s response to Gabriel – both Peter and Mary acknowledge they are in receipt of hearing God’s Word. The more I let the text of Luke 5(1-11) wash over me, the more I sensed the presence of the spirit of the Magnificat prayer. Luke is writing Peter’s magnificat here in Chapter 5:1-11. Both Peter and Mary are amazed, astonished, pondering, captured by the moment of divine presence – Peter prior to the fishing success; Mary prior to her “virginal’ conception. Both Peter and Mary experience the presence of the Holy Spirit – as ‘authority’ and not just ‘raw power’. Which brings Nathan’s sermon back into full view- both Peter and Mary are empowered as they experience fully their total humility – being loved as being forgiven. Thanks Nathan – you speak as one who understands and knows that sense of ‘authority’ in Jesus’ Word.

I’m very confident that any 5 second Google search on the topics of sin coupled with unworthiness would come back with many a sermon. I’m also confident that many of those said sermons would be theologically unsound because they would not give us a pathway out and doom us to a fate in hell.

This is indeed ironic because the roadmap out, salvation via the acceptance of grace, is free to download, visible and accessible to all. And yet, we often fail to even see it, much less access it.

As “the church” we’ve taken the great reversal embodied in Jesus and re reversed ourselves as though we are living in a world where Jesus has not yet come.

This sermon deserves to be at the top of any search for sin and unworthiness.

Thank you for this sermon – I have read it every week for the last 3 weeks and have discovered that it makes sense of a number of questions that I have had but not been able express in words as I really did not know what the questions were

As with the wisemen – the sight of the Christ child changes them and they return home a different way but the sight of our sin simply causes us to despair, I have never been able to preach on sin as such – where as to speak of the glory of God will show us our sin.