A sermon on Jeremiah 17:5-10 & Luke 6:17-26 by Nathan Nettleton, 17 February 2019

There have been more than a few jokes about you all waiting with bated breath to hear what I might have to preach after my two weeks on retreat in the desert. And what do you know? My first time back in the pulpit and our first reading uses the imagery of the desert. Those who trust in their own strength, says the prophet Jeremiah, “shall be like a shrub in the desert, and shall not see when relief comes. They shall live in the parched places of the wilderness, in an uninhabited salt land.”

That imagery is very vivid to me after being in a place where the temperatures got to 48°C, and I saw shrubs whither and birds fall out of the sky, killed by the heat.

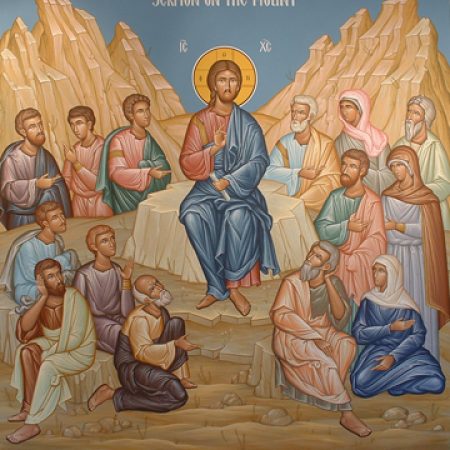

But I’m going to circle back to those words of Jeremiah after first exploring the words of Jesus from our gospel reading. We heard the beatitudes from Luke’s gospel; somewhat shorter and sharper than the better known version from Matthew’s gospel. In both, the beatitudes are the opening paragraph of a lengthy sermon given by Jesus to the crowds. We usually call it the sermon on the mount, although Luke locates it on a plain as a sign of the word of God coming down among the people.

Actually, our passage from Jeremiah could be described as the prophet’s version of the beatitudes, because like the words we heard from Jesus, it is structured arounds some contrasts between what it means to be blessed, and what it means to be cursed, or facing spiritual disaster. But let’s look at Jesus’s version first.

Luke’s account of the beatitudes records just four statements about those who are blessed – Matthew has nine – but Luke pairs them with their opposites, four statements about those who might have been thought of as blessed, but who are anything but blessed in the eyes of God. Most Bible versions translate it as “Woe to you who are …” Or we might render it as “The writing is on the wall for you who are …”, or “What a disaster for you who are …”

If we haven’t been inoculated by over-familiarity, the shock is that the things that Jesus describes as being disastrous are precisely the things that most of us aspire to most of the time: being financially secure, well fed, happy, and well regarded by those around us. If you want to recover the shock of those words, imagine applying it to our children. Imagine Jesus pointing at these children over here and saying, I hope and pray that they grow up to be poverty stricken, malnourished, gripped by grief and sadness, and despised by almost everyone mainstream society.

Do any of you think you could join him in such a prayer? I didn’t think so. So what’s going on?

There’s a simple answer, and like most simple answers, it is probably wrong. The simple answer is that it is all a matter of timing. Being wealthy, well fed and happy is a good thing, but it’s better to get there in some future eternity than to peak too early and have it taken off you. Life in eternity will still be divided into the haves and the have-nots, but the present rankings will be reversed. It’s like priority picks in a spiritual draft system. Finish the current season being the biggest loser you can so that you’ll get priority draft picks and rocket up the ladder next year.

Like I said, it’s a simple answer, and it’s almost certainly wrong. Jesus is not on about creating yet another system of winners and losers, albeit in reverse. Jesus is on about completely abolishing systems that require anyone to lose.

But Jesus certainly is on about upending our values systems. When he first spoke these words, they would have been every bit as shocking and unthinkable as that imaginary prayer for our children. And in his day it wasn’t just understood as the values of society. It was understood in religious terms as the values of God. People always aspire to be prosperous, well fed, happy, respected and popular. But in those days, most people also believed that those things were blessings from God. Prosperity, happiness and popularity were seen as God’s rewards bestowed on those who were good enough to deserve them.

You can find churches that still teach this today, despite the clear teaching of Jesus to the contrary. In the news this week we’ve seen allegations against another prosperity preaching, charlatan preacher here in Melbourne who made himself filthy rich by fleecing his congregation, though that probably wouldn’t have made the news had he not also sexually abused a series of women in his church. A man so convinced of his own blessedness that he felt entitled to grasp all manner of privileges without regard for who paid the price.

So in a culture that had always believed that the trappings of success proved that you were a good person blessed by God, Jesus saying “Blessed are the poor and woe to the rich” was as unexpected and bewildering as if he’d told us that Tony Mokbel and Donald Trump were God’s chosen role models for us all to follow.

Here’s the thing: both then and now we constantly confuse God’s expectations with our own social constructions of niceness and goodness. And unlike God’s expectations, our social constructions of goodness are nearly always based on condemning others to the role of failures, losers, problems, misfits or just plain bad. They are unable to conform to the social expectations of mainstream society about what is good and proper. So “I know I’m good because I’m not one of them.”

Having been cast out of the realm of the good and right and normal, they soon fall outside the realm of our concerns and our care. They even become the people we can blame for whatever is going wrong. So we see asylum seekers and refugees as lawbreakers and criminals trying to breach our borders, and then as people to whom we don’t even have to provide proper medical care when they get sick while being detained by our forces. They can stay sick, because we have dehumanised them. We are blessed, they are cursed. End of story. End of care.

There is a Royal Commission just getting underway that is already holding up frightening evidence of how we have done the same thing to many of our frail elderly folk. If they lack sufficient financial resources and family supports, when their health and ability to contribute declines to a level where they fall outside of our social construct of normal useful good people, we have too often shut them up in so-called “care” facilities that are anything but caring, where their money is taken in return for appallingly sub-standard accommodation, food and support. That sort of thing might only be a small part of the aged-care sector, but we have largely turned a blind eye, not really thinking that these people matter.

Our treatment of people with mental illnesses has been even worse. Their inability to conform to our ideas of normal often makes us feel uneasy and anxious, and so we want them off the streets and kept out of view where we don’t have to see them or think about them. And precisely because so many of us didn’t want to know, numerous psychiatric facilities have become some of the most toxic cesspits of abuse and mistreatment imaginable. We keep sending sick people to them, because we have no idea what else to do, but the sexual abuse and violence that so often takes place means that people are often worse off after “treatment” than they were before.

Asylum seekers, the frail elderly, the mentally ill. I could go on. There are so many groups of people who don’t fit our expectations of what’s normal and good and socially acceptable. So many groups who, although we might not say it, we regard as the cursed, the outcast, the unwanted. We’ve built our world, and they don’t have a place. We have a place because we are the blessed, but not them.

But Jesus comes barging in to upend our tables and set free those we have locked away. Jesus comes declaring that the poor and the hungry and the asylum seekers and the frail elderly and the mentally ill are at the centre of God’s care and God’s love, and that the emerging culture of God will seat these people in places of honour. Blessed are they.

This is not an either/or for Jesus. He is not just reversing the system and sending the rich and well fed and socially successful off to the places of shame and humiliation. He doesn’t say “Cursed are the rich”. He says “Woe to the rich.” How is that different? Well, it is a bit like what he said elsewhere when he said that it is as hard for a rich person to get in to the culture of God as it is for a camel to get through the eye of a needle. Or like when he told the rich young man to give away all he had and come follow him.

You see, everyone is called, but not everyone sees the invitation as a blessing. Those who do are usually those with nothing to lose. The poor, the hungry, the refugees, the mentally ill. Those who have known so much misery and abuse will not feel torn about trading their past for a seat at the banqueting table of God. But those of us who are well accustomed to being the privileged ones, the special ones, the righteous and respected and honoured ones; we are not going to be nearly so attracted to a new culture in which all that counts for nothing and there is no longer any recognition of our special status.

This is why so many Christians still cling onto the idea of a God who will send bad people to hell, because that would mean that God was still recognising our special status as the good respectable people. But Jesus was clear here in the beatitudes and elsewhere in some of his conversations with the religious elite of his day. “The prostitutes and outcasts and sinners are getting into the realm of God more easily than you,” and it’s precisely because they know they’ve got nothing to lose, while we respectable religious people are turning up our noses and feeling sick at the very thought of lowering ourselves to go where they go and sit where they sit.

All our lives we have thought that the worst thing in the world would be to fall through the cracks and end up where the asylum seekers or frail elderly or mentally ill end up. But now Jesus is telling us that where they end up is seated at the banqueting table of God, and he’s inviting us to end up where they end up, seated alongside them. No wonder we experience it as a great woe.

It is actually the most astonishing blessing, but we are so conditioned to the lie that says that we only win if others lose that we find it desperately painful to let go of our status as the winners. This table that we gather round is a table from which no one is excluded. It is the table of Jesus, a table where the losers win, and where the former winners will win too if they are willing to stand here arm in arm with the former losers and share the prize, share the feast. That’s extraordinarily good news, but as Jesus acknowledged, it may not feel like it to those of us for whom the status quo has seemed like good news.

Let me return before I close, to Jeremiah’s desert version of the beatitudes. His version is very simple. Trust in God, and you will be blessed. Take things into your own hands, and you will dry up like a shrub in the desert. It is much the same thing as what Jesus was saying. He just noted that it was much easier to trust God when everything else has failed you. When the success systems of mainstream society have served you well, trusting a God who invites you to turn your back on all that is so much harder to do.

During my recent retreat in the desert, I noticed something about how this affects me personally in the way I have understood my work as a pastor. It’s something that has been starting to fall apart for me, and it was leaving me unsure of who I was and what I was doing as a pastor.

You see, I have had far more trust than I realised in my own strength, in my own ability to achieve things and make a difference. I have tended to understand myself and my ministry as contributing to the salvation of the world, to the turning around of the world’s suicidal slide into self-destruction. But in the last couple of years, I’ve been forced to face the fact that that slide into self destruction is continuing unchecked. Politics is getting madder and madder. Climate change is reaching the point of no return. Churches are becoming more mired in fear and divisiveness. Nothing I can do is going to turn it around.

But I’m not finding it easy to let go of my belief in myself as someone who could make a difference, who could achieve something, who could help turn things around. I’m not finding it easy to hear Jesus saying blessed are the unsuccessful; blessed are the despairing; blessed are those whose efforts are dismissed and derided and ultimately futile. That’s not the blessing I was seeking.

But the same Jesus knew that even he couldn’t turn things around. “Jerusalem, Jerusalem. How often have I longed to gather you in my arms like a hen gathering her chicks, but you refused, and now you are doomed.” That’s not a place I wanted to stand or a cry of despair I wanted to utter either. I wanted to be effective, but actually Jesus has only called me to be faithful, faithful even if it brings only tears.

Blessed are those who can give up trusting in their own strength, their own effectiveness, their own importance. Blessed are they who can surrender all that and leave it to God, for they will be like trees with deep roots that can reach the water of life even when the desert heat hits 48 degrees, and everything we thought we could do is wilting and dropping.

Blessed, blessed are they who know that real life is not found in their own effectiveness or success, but in the life of God given to us in the broken bread and poured wine at this table.