A sermon on Matthew 5:1-12 by Nathan Nettleton

A video recording of the whole liturgy, including this sermon, is available here.

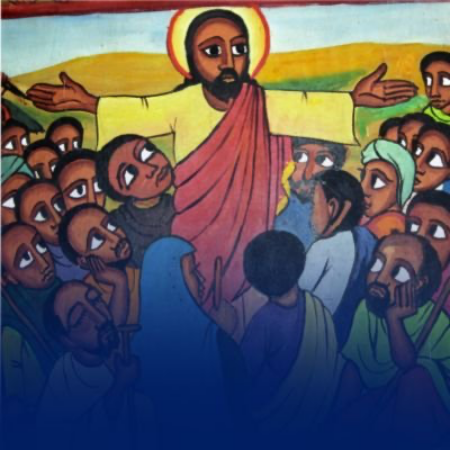

The largest slab of Jesus’s teaching that we have in our Bibles is known as the Sermon on the Mount. It goes for three chapters in the gospel according to Matthew, and we heard just the first twelve verses of it read tonight. Commonly known at the Beatitudes, this section is easily the best known. Not always for the right reasons though.

Perhaps our most common encounter with the Beatitudes is as tame platitudes on greeting cards or wall hangings. The context tends to make them seem sweet and comforting and kind of harmless. Chicken soup for the soul rather than anything that is going to upend the world as we know it.

Those of us who have more often encountered the Beatitudes in sermons or Bible studies in churches might have experienced them in other ways. We may have heard them presented in ways that made us feel ashamed of our comforts and privileges, as though Jesus was saying that we are inadequate and contemptible for not being poorer, hungrier, mournier, and more persecuted. This is not what Jesus was saying, and if you’ve copped some of that kind of teaching, it might help to remember that Jesus was criticised by his opponents for being too much of a party animal, an alleged glutton and drunkard. He was not known for putting on a long face.

Another way you might have experienced the Beatitudes in sermons or Bible studies is as a kind of spiritual check list or to-do list. In a way, our combination of Bible readings today pushes us in this direction, because our reading from the prophet Micah (6:1-8) suggests that since God has been so good to us, we owe it to God in return to behave as God wants. And when you read that alongside the Beatitudes, they can easily sound like a list of behaviour standards to be worked towards. But while that might work okay for some of them – more mercifulness and peacemaking are desperately needed in our world – it doesn’t make much sense with others. Trying to get yourself more hated and persecuted is not healthy, although I have encountered some Christians who seemed intent on pursuing it anyway.

I’m not saying that the Beatitudes have nothing to say about how we should live, and I’ll get to that shortly, but the other problem with this checklist or to-do list approach is that it tends to feed into a very transactional understanding of our relationship with God. The to-do list becomes like a list of tasks set for us by a tight-fisted employer who will only pay us if we prove ourselves sufficiently productive. It might be slightly better than the view that God is intent on punishing anyone who doesn’t measure up, but a God who only dispenses blessings when they are paid for with transactional achievements of goodness is not the extravagantly generous God revealed to us by Jesus.

In fact, the first thing we should learn from the Beatitudes is that the exact opposite is true. Blessings come first. Blessings are not being withheld by a tight-fisted God. They are God’s first move. Blessings are being splashed around with reckless abandon, and our relationship with God begins not with a grovelling attempt to earn something, but with discovering ourselves blessed. Remember, these are the opening words of Jesus’s first sermon in this gospel, and the opening word is “blessed, blessed, blessed.” The word “beatitude” comes from the word that means blessed, the word that comes first in each line of the Latin version of these verses. Blessed, blessed, blessed.

Why then, you might ask, is Jesus singling out these particular categories of people and pronouncing them blessed? If it all starts with God’s open-handed blessing, why doesn’t he just say that everyone is blessed?

Well, I think it is a bit like that debate about whether we should say “Black lives matter” or “All lives matter.” Sometimes it only needs to be said in relation to those for whom it is not already obvious or taken for granted. In a world where black lives are frequently treated as mattering less, it becomes important to state that they matter. We are not saying they matter more, but that they matter too, and they matter just as much.

So perhaps what Jesus is saying here is a lot like that. There is no need to highlight the blessedness of the wealthy and comfortable and happy and successful. Their blessedness is taken for granted and obvious to all. In Jesus’s day, religious teachers mostly thought that wealth and success were not just blessings but rewards from God for lives lived according to God’s expectations. But the idea that the poor and the hungry might also be those who Jesus would bless was considered very strange and questionable. Jesus seems to be running around blessing everyone in most unexpected and scandalous ways, as though he thought blessings grew on trees and were available to everyone.

We are living in a time when the president of the most powerful nation on earth can stand up and say I tried being a peacemaker, but they wouldn’t give me the Nobel prize, so I’m not so interested in making peace any more. There’s some transactional thinking for you! But seriously, peacemaking, mercy, meekness, purity of heart – these are all things that are routinely dismissed as sounding nice but not working very well, not likely to achieve the kind of success that is sought after and considered blessed in our world.

So when Jesus starts blessing those who exhibit these things, he is certainly not stating the obvious. He is bestowing blessing where it was assumed that blessing was absent and not even deserved or appropriate. But he is not just filling in a gap, is he? By blessing the unexpected ones, Jesus is painting a picture of a world turned upside down, a world where the accepted values systems are turned on their heads.

When placed in the context of the ruthless world we live in, just like the one Jesus lived in, these beatitudes sound to many like “blessed are the losers, blessed are the losers, blessed are the losers.” Look at the values that are being played out in the USA at the moment. Not because they are so different to the values in play here, but because America always seems to do things in a more exaggerated way that makes it so much more obvious to the naked eye. Look at their intervention in Venezuela, or their threatened takeover of Greenland, or internally at the gestapo-like purge of foreigners from their neighbourhoods. Standing up for the blessedness of the meek, the merciful, and the persecuted in front of a line of masked Federal ICE agents could put you at risk of being shot.

But this blessedness is telling us something crucial about God and about where God can be most readily found in our world. God’s love reaches out to everyone, no exceptions, but if you want to see where God’s life is being welcomed and nourished, there’s probably no point starting your search among the wealthy, the powerful, the successful, the celebrities. It is not that they are not blessed, but that their blessings are hoarded, flaunted, exploited, and taken for granted. They are more likely to be shutting God out and claiming all the credit for their own blessing. And if I’m honest, I’m often not so different from that.

But, as Debie Thomas puts it:

What Jesus bears witness to in the Beatitudes is God’s unwavering proximity to pain, suffering, sorrow, and loss. God is nearest to those who are lowly, oppressed, unwanted, and broken. God isn’t obsessed with the shiny and the impressive; God is too busy sticking close to what’s messy, chaotic, unruly, and unattractive.

Following God into such places really goes against the cultural flow of our world. It’s seriously pushing upstream. But as G.K. Chesterton once said, even “a dead thing can go with the stream, but only a living thing can go against it.” Going with the flow is no evidence of life at all, let alone quality of life. It’s the ability to make progress in the opposite direction to that which the culture around you would naturally and rather mindlessly sweep you, that shows that you are well and truly alive. Jesus does not call us to be contrary simply for the sake of it, but he certainly wants us to swim out of the main stream and invest ourselves in the places where God is most invested.

Which brings us back to this question of what the Beatitudes do have to say about how we should live. I said they are not a to-do list – try hard to be poorer and meeker and more pure of heart – but that doesn’t mean they have no implications for how we live and invest our lives. In fact, one of the frequent abuses of the beatitudes has been to see them as pie-in-the-sky-when-you-die with nothing to say about life in the here and now, and at its worst, they’ve even been used to tell the oppressed and downtrodden that they should just accept their fate because they will be blessed for it by and by. That is monstrous perversion of Jesus’s words.

But what do they say about living our lives in the here and now?

Well, firstly, as I have just implied, they tell us not to just go with the cultural flow of the society around us, worshipping power and success and celebrity, and avoiding anything that the world regards as signs of being a loser. Instead, recognise all of life as blessed, and all people as worthy of being blessed, especially those who are most often excluded and disregarded. As Mark Wilkinson said in last week’s sermon, we are called to recognise every person as someone who is made in the image of God and is loved and blessed by God.

Secondly, and I hope somewhat obviously, since we are followers of Jesus we are called to do as Jesus does, and that means that his Beatitudes call us to be blessing those who the world seldom blesses, and to be blessing them both in word and action, just as Jesus did. The Beatitudes may be an example of Jesus blessing people by simply speaking words of blessing to them, but Jesus was never all words. The words he spoke are words he lived. As his followers, we are to follow him in doing the same.

Jesus does not regard human misery as a blessing. But he does regard every human, even the most miserable, as people who he can bless and be a blessing to. That can be difficult to do anyway, when it goes against the flow of our society, but it can be a lot more costly than that too. Renee Good and Alex Pretti were shot in the streets of Minneapolis for seeking to be a blessing to their immigrant neighbours. They followed in the footsteps of Jesus who was similarly crucified for being a blessing to those who the authorities of his day said should not be blessed.

But says Jesus, “Blessed are you when they revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely for righteousness’ sake. Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for in the same way they persecuted the prophets who were before you.”

We are blessed to be a blessing, and in being a blessing to those who are seldom blessed, no matter the cost, we come close to the God who blesses and blesses and blesses, and we are blessed, over and over and over.

0 Comments