A sermon on 2 Samuel 11:26 – 12:13a by Nathan Nettleton

The sermon I preached last Sunday was described by some of you as “a hatchet job” on David. You were quick to reassure me that you weren’t saying that I was wrong, but just that the popular public image of David took an almighty battering when I described him as a rapist. In a way, it would be interesting to explore that response, because if I’d just said that David was a murderer, no one would have batted an eyelid. Everyone accepts that the story says that. I wonder what it says about us that we have been able to reconcile David as hero with David as murderer, but we still get thrown if he is accused of further crimes.

I’m not going there tonight though, because the biblical story has moved on, and the preacher needs to move on with it. And besides, one of you made the hatchet job comment in the context of saying you couldn’t wait to hear how I was going to address David’s repentance after that, and indeed, David facing up to his crimes is precisely where the story takes us tonight.

We don’t need to make anything of the fact that the prophet who features in this story happens to be my namesake. Those of you who are named John or Peter or Mary encounter your namesakes in the Bible all the time without needing to make a big deal of it. We only notice my one because he doesn’t come up very often, so that’s enough said about his name.

There are a few things in tonight’s reading that do deserve, or even demand, at least brief comments before we get to explore David’s repentance in detail.

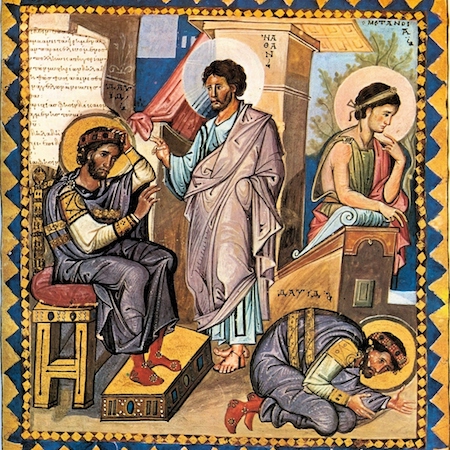

The first is for those who might still be feeling that last week’s hatchet job was overdone and perhaps unfair on David. Perhaps you are still more persuaded by the conventional romantic view that this was an adulterous but mutual love affair, and not a rape. Well, take note of the story that Nathan uses to unmask David’s actions. He doesn’t say that the rich man fell in love with his poor neighbour’s lamb and seduced it into coming over for the barbecue. The lamb is not a love-struck willing party to its own barbecuing. No, the lamb is an innocent victim, violent seized against its will. This is how Nathan depicts David’s crime. And the Hebrew text uses exactly the same word for the seizing of the lamb as it used to tell us that the palace guards seized Bathsheba and delivered her to the king.

A second thing to mention is that there are a couple of elephants in the room with this story, and while I’m not going to focus on either of them, I want to at least acknowledge them with a brief comment. One of them was hidden from us tonight by where the lectionary chooses to end the reading, but many of you will know the story, and we’d have only had to go another verse and a half to trip over it and hear the prophet say to David, “Now the Lord has forgiven your sin; you shall not die. Nevertheless, because of your deed, the child that is born to you shall die.”

What sort of god would pardon the guilty party and kill an innocent baby instead? The short answer is ‘not the God made known to us in Jesus’. We do know that evildoing has generational consequences. Coming generations are going to pay the price for our generation’s failures to do enough to halt greenhouse emissions. Serious domestic violence and abuse often has horrific consequences for several generations.

The Hebrew scriptures, however, accurately preserve a record of an era that believed that everything that happens is the doing of God, and that therefore such consequences are punishments willingly inflicted by God. Our trust in the Bible though is not in each and every passage in isolation, but in its unfolding teaching, with Jesus as the interpretive key, and Jesus quite explicitly refuted the then common belief that all suffering was divine punishment (e.g. Luke 13:1-5). Through his own suffering he showed us that when suffering is inflicted, God is always and only on the receiving end.

The second elephant in the room does segue into our main topic. It is the question of whether David gets off far too lightly. Is his repentance even vaguely proportional to his crimes, or is this just another case of the wealthy and powerful managing to get off far more lightly than the poor and under-resourced?

The question is quite justified, and can’t be fully answered. David admits that he was wrong, but what is recorded of his confession only refers to his sin against God and makes no mention of his human victims, Uriah and Bathsheba. And in our justice system, even the most thorough confession in the world does not earn you a full pardon for murder and rape. It probably didn’t for anyone else in those days either, so we are probably just going to have to live with this elephant of inequality. If you or your loved ones have had your world shattered by rape or murder, that’s not likely to be very helpful. All I can do is say I hear your pain, and I apologise for not addressing that properly in this sermon, but if you want to talk with me about it, I won’t avoid it then.

The question of whether David’s acknowledgement of his own wrongdoing is adequate is more complicated. Did he properly acknowledge the harm done to his victims? We can’t know. If he did, it’s not recorded, and that disturbs us, but it doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. Last year our church received a letter of apology from someone who perpetrated abuses here in the past. It looked quite genuine, and we hope and pray that it was, but it didn’t name the victims or the wrongdoings – it just said ‘I’m sorry for everything’ – so it was impossible for us to know whether our respective perceptions of “everything” were on the same page. David’s confession feels a bit like that, but not quite. His confession comes as an immediate response to a specific accusation, so that gives it some real content, and we can make some judgements about his genuineness from what we know of his subsequent life and career.

Now we’re getting to the heart of where I want to take us with this story tonight, and I think that if we are tempted to cast too much doubt on the sincerity or adequateness of David’s confession and repentance, we should at least pause to reflect on how surprising it is that it comes at all. Major political power brokers do not often fess up to wrongdoing on any scale.

David could easily have silenced anyone who had any dirt on him, just as he had done with Uriah. There are a number of other prophets and whistle blowers in the Hebrew scriptures who stood up to kings like Nathan did, and who were promptly jailed or killed for their troubles. The same thing today can result in political murders too, or in other cases in relentless social media campaigns denouncing the allegations as fake news and the reporters as the enemies of the people. Unqualified mea culpas are very rare indeed.

Nathan’s approach was carefully calculated to get around David’s power-drunk defences, but the risk was still huge. Fortunately for Nathan, the strategy worked.

He didn’t march in and accuse David directly. Instead, he tells a parable purporting to be a report of a case that is being brought to the king for judgement. An anonymous rich man holding a spit roast doesn’t choose an animal from his own huge flocks and herds, but seizes the one and only beloved pet lamb from the impoverished family next door and barbecues that instead.

The description stirred up in David the kind of compassion and outrage that we wish he had felt earlier. He explodes with anger against the “callous perpetrator” in the report, particularly condemning the complete lack of compassion, all the while completely failing to see his own glaring public hypocrisy.

Unless David’s outrage is just posturing for an audience, just virtue signalling as we call it today, then his gut stirring anger at the injustice is at least some evidence of the remnants of a moral compass. His arrogance may have swamped all self-awareness, but he can still recognise and be horrified by ethical failures in others. But right at the point where David assumes the role of judge, or moral guardian of the community, Nathan delivers the thunderbolt judgment: “You are the man. You are the perpetrator.”

Driving it home, Nathan follows up by channelling the anguish of God in what sounds like one of those “after all I’ve done for you!” lectures that come from parents who feel betrayed by the bad behaviour of their children. “Why did you do it, David, after all I’ve done for you?” It seems that when we turn our backs on God and behave abominably, God takes it personally. “Why did you do it, after all I’ve done for you?”

The answer to that why question is complicated though, for us as it was for David. We, like David, are often blind to any real awareness of what we are doing. Powerful men like David are often blinded by a belief in their own importance, their own uniqueness. Surely someone like me who does so much for the people deserves a little slack, a little comfort, a little self-indulgence, and a little shelter from troublesome journalists.

Most of us don’t have quite such delusions of grandeur and omnipotence, but we get blinded by other aspects of the culture around us with its self-protective instincts. With our consciousness heightened by the #MeToo movement, most men I know have realised that there are things in their pasts that they now realise look pretty questionable, but which at the time seemed perfectly normal and appropriate in the culture we lived in. Having our eyes opened is a painful and terrifying thing.

In our weekly prayer of confession here we confess that we are entangled in sin, and it’s true. Sometimes we sin because we make calculating corrupt decisions, but more often we are helplessly entangled in systems and worldviews and cultural perspectives that blind us to the ways our actions impinge on the lives of others. We can become participants in horrendous evils without even realising it.

If a modern day prophet comes pointing the finger at me and telling a parable about wealthy people whose televisions and mobile phones and jeans roll out from supply chains full of child slavery and sweatshops and rape of the earth’s resources, I’m going to have nowhere to hide. Like David, I might be able to recognise my own guilt without being able to name the victims, because these structures of evil deliberately keep me in the dark.

It is all too easy for us to point to the sins of wealthy and powerful celebrities. Such public condemnations are often necessary and entirely justified. Public crimes need to be exposed and condemned in public. But beware of doing a David and exploding in rage at the sins of others while remaining blind to your own. When the prophet declares that our lifestyles, our comfort come at a great price and that this price is being paid by the poor and the broken of the world, will we have the humility and integrity to acknowledge our guilt and strive to reconstruct our lives around new visions of compassion and justice and loving care for the least of these?

Facing up to David’s sin, and facing up to our own, can shake our world to its foundations. We instinctively want to keep the world neatly divided into good and bad, and we want our heroes to be unambiguously good. It helps us to reassure ourselves that we too are good people, and that we have earned God’s love and protection.

But one of the things this story tells us is that no matter how much we want to view the world in simple shades of black and white, God does not carefully vet the moral suitability of those who are blessed to be used in God’s mission in the world. Spectacular sinners like David and ordinary but hopelessly entangled sinners like us are gathered into the divine mercy and love, no differently from one another.

When that happens, and we recognise ourselves there, the invitation to us is the same as the one we see David responding to as his story continues to unfold. We are invited into the often painful, sometimes tragic, but exquisitely beautiful journey of becoming fully human, a journey from the sort of inhumanity we see in David’s calculated and callous crimes, to the growing humanisation we witnessed earlier as we sang David’s more extended confession in the words of Psalm 51. God is always calling us back to integration, to integrity, to a place of healing where God’s generous mercy and love can heal us and restore our undivided selves.

We have glimpsed it in the way David’s story unfolds after this event, and we have tasted it more fully in the ministry and teaching of Jesus. It is he who has shown us that the worst atrocities that we can commit cannot forever entomb the love and mercy of God. It is he who calls us to be the change we long to see in the world by beginning with genuine heartfelt repentance for our blind complicity in the corruptions that bereave and impoverish the world and its peoples. And it is he who beckons us to behold a vision of a new world raised from the ashes of our deluded self-righteousness, and to humbly but joyously welcome that world as it comes dancing towards us on the love song of the Spirit.