A sermon on John 18:33-37 by Nathan Nettleton

A video recording of the whole liturgy, including this sermon, is available here.

Today is the last Sunday before the season of Advent, and it is designated in the Church’s calendar as the Feast of Christ the King. The relatively short history of this Feast of Christ the King highlights both some very embarrassing mistakes that the Church needs to repent of and be constantly self-examining about, and some delicious ironies that, if they are allowed to shine forth, can provoke us towards a new grasp of the truth of who Jesus is and what he was on about.

The reading we heard from the gospel according to John captures these ironies beautifully as Pilate and Jesus tussle over whether or not Jesus can be charged and convicted with setting himself up as a king. “Are you a king?” Pilate asks. Jesus doesn’t say “no”, but he doesn’t say “yes” either, which surely should have stood as a warning to so many of his followers ever since who have been all too keen to portray him as a king.

A quick look at the history sets some warning bells ringing. The Feast of Christ the King was created, with no prior tradition, exactly 99 years ago by Pope Pius XI. Pius was negotiating the Lateran Treaties with Mussolini to sure up the political status and independence of the Vatican. As part of the deal, the Vatican took action to suppress the only democratic party in Italy. Pius didn’t much like democracy. He preferred monarchies and authoritarian regimes because he found it easier to negotiate treaties with them which favoured the Roman church. Both Mussolini in Italy and Hitler in Germany granted the church wide-ranging favours in exchange for political silence.

The Feast of Christ the King was, therefore, created with a political agenda, to reinforce the message that the Church wanted obedient subjects and that the Kingship of Christ was expressed through an absolute European monarch, and to thereby sure up the Vatican’s power and the power of those regimes with whom the Vatican had negotiated expedient cooperative arrangements. Thus we now have the anomaly of a feast in our calendar which arose out of a devil’s pact between the Church and the Fascists!

Now as ugly and embarrassing as that is, it probably shouldn’t come as any great surprise to us. And as desperately as we might want to repent of such things and perhaps even throw this feast back out of our calendar as an expression of our repentance, sometimes it is better to leave these monuments to our mistakes in place as a perpetual warning, and allow the ironies that emerge from them to continually challenge us and re-educate us.

You see, although this feast day might have only been created in 1922, the difficulty of getting our heads around what it might and might not mean to think of Jesus as a king has a much much longer history than that. Our difficulties with sorting it out put us in the company of the very first followers of Jesus. The likes of Peter, James and John kept thinking that Jesus was going up to Jerusalem to overthrow the Romans and reestablish the throne of David. His failure to do so was probably the largest cause of Judas’ loss of faith in him. And the gospels recount several instances where the crowds, who were so enamoured by the things that Jesus said and did, tried to take him and proclaim him king, whether he wanted it or not, and he had to run away and hide to avoid his own coronation.

So by the time Pilate asks him if he is the king of the Jews during his interrogation, there is already quite a history to this, and the question is more serious and more complex than just a trumped up allegation by his religious opponents. And for much of our history, we’ve gone right on doing the same thing. So often we have fallen into triumphalism and sought again to make Jesus king by force so that, like any other king, he can lead us into battle and kick the crap out of our enemies. Over and over again, every time we’ve proclaimed that Jesus is king, we have been sucked into thereby thinking of him as a powerful ruling figure, with a crown and a sceptre and a raised sword, triumphing over every opponent and crushing enemies under his feet.

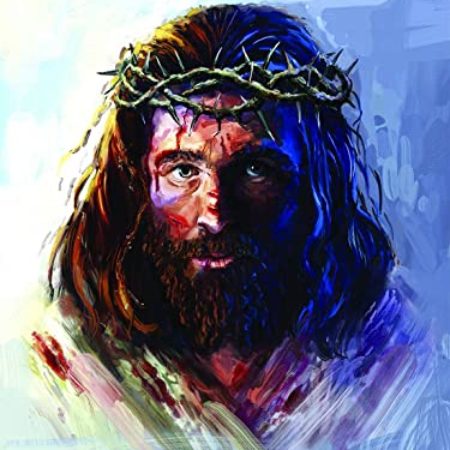

Even when we are not literally wanting him to be a warrior king who guarantees our military victories in real-life wars, we are often succumbing to the same conquering mindset at a figurative level, and wanting Jesus to help us put the fundamentalists under our feet, or crush the politicians whose policies we despise, or perhaps even just humiliate the architects of Australia’s so-called climate plan that has embarrassed us all on the world stage in recent weeks. Faced with such enemies, even left leaning, peace and justice oriented, pacifist greenie Christians can end up longing for a king who will ride in on a great white steed and conquer the bad guys. A donkey riding, crown of thorns wearing, political prisoner just doesn’t cut it.

But a donkey riding, crown of thorns wearing, political prisoner type of king is precisely what we have to come to terms with, whether that suits Pius XI or not. That may have been what lay behind Pilate’s question. He may have been looking incredulously at the anything but regal figure before him and saying “Are you the King of the Jews? You?”

And while Jesus doesn’t quite refuse the title, he does make it clear that if he is to wear it, it doesn’t mean anything like what everyone, and especially Pilate, thinks it means. “My kingdom is not from this world. If my kingdom were from this world, my followers would be fighting to keep me from being handed over.” Do you get that? If my kingdom were the sort of kingdom you understand, and I were the sort of king you would recognise, then my followers would be fighting. They’d be fighting, because that is what the followers of kings do, isn’t it? Because that is what kings are all about. Fighting. Conquering. Imposing their will and their reign at the point of a sword or the barrel of a gun.

Jesus is giving us, as his followers, a big loud warning here. A warning we have all to often missed. He is telling us that “king” is probably entirely the wrong word to use of him, or at least it is entirely wrong if by it we mean that Jesus can be understood by looking at other kings and saying that Jesus is like that, only even bigger and better and stronger and more powerful and conquering than any of them. He is telling us that if we want to speak of him as king, then we had better be aware that we are redefining the whole concept of what a king might be. We are turning it on its head and using it is a way that is cryptic and ironic and perilously easy to get confused and led astray by.

Pilate, of course, quickly picks up on the fact that Jesus does not absolutely refuse the title of king. Pilate knows that defining the kingdom as not from this world does not mean that it is of no consequence to the power of Rome. ISIS think that their caliphate is not from this world too, and that doesn’t make them any less of a threat.

Being a king was not in and of itself a crime so far as Pilate and the Roman Emperor were concerned. King Herod was a Jewish king, and he was allowed to continue his reign. What Pilate and the Emperor wanted to know was whether a local king was willing to bring his rule under the rule of Rome. So if Jesus had presented himself as a king of the type that Pilate could understand, that wouldn’t have immediately led to his execution, whatever the Jewish authorities were hoping for. It would more likely have led to the exactly the kind of negotiations that later went on between Pius XI and Mussolini.

Are you a king we can live with and work with and do business with, or do we have to send in the troops and conquer you to prevent you from becoming a threat? In Pilate’s world, it doesn’t matter whether your kingdom is from this world or from somewhere else. What matters is whether those who call you their king do so in opposition to Caesar or in recognition that you are a servant of Caesar and that therefore in putting themselves under your rule they are putting themselves under the higher rule of Caesar.

But Jesus insists on defining himself in quite different terms. “You say that I am a king. For this I was born, and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice.”

Now we’re in deep trouble. “Truth!” Pilate sneers. “What is truth? We’re talking about power here. We’re talking about who rules over who, and who gets to call the shots. What has truth got to do with it?” Donald Trump frequently posed that question too, although perhaps not quite as explicitly. For kings and emperors and any other kind of political power brokers, truth is only ever an ally when it is the scandalous truth about one’s opponents. Truth is something to be managed and controlled and regulated. Not something you base your reign upon.

If Jesus is going to be a king who answers always to the truth, then he is certainly not going to be compliant to Caesar and his fate is sealed. And so it is straight from this interview that Pilate hands him over to be flogged and they dress him in the purple robe and stick the barbed wire crown on his head and begin to assault and humiliate him.

So this story, set for reading on this day, stands as a bold exposé and warning of exactly the kind of attitudes and behaviours that led to the creation of this feast day in the first place. For if this is the Feast of Christ the King, it is not the feast of a powerful king seated triumphantly on a throne with his enemies under his feet, and thus endorsing us to do likewise in his name, but the feast of a royal political prisoner under arrest and being interrogated.

It is not the feast of an authoritarian king who makes laws and enforces them and dispenses punishment, and thus endorses us to do likewise in his name, but the feast of a king who is held hostage and soon to be beaten and tortured and crucified.

It is not the feast of a mighty warrior king who conquers and demands submission, and thus endorses us to do likewise in his name, but the feast of a king whose only involvement in violence is as its innocent victim, never as its perpetrator; a king who absorbs all the hatred and hostility and violence that a bitter world can heap upon him and returns only love and forgiveness and generous blessing.

So let us keep the Feast of Christ the King, for if we belong to the truth and listen to his voice and go with him as he subverts the whole concept of kingship and calls us to follow; if we give our allegiance to him as king on those terms, we and the world we live in might never be the same again.

One almost wants to ask the question “is this true?”

If the answer is “yes” – the sermon preached must be very different then the one that first comes to mind