A sermon on Lamentations 1:1-6 & Psalm 137 by Nathan Nettleton

A video recording of the whole liturgy, including this sermon, is available here.

You might reasonably think that a religion whose central symbol is the cross – a sign and implement of horrific suffering – would have a decent handle on how to process, understand, and respond to tragedy and suffering, but it has often not been the case. Christian churches have frequently been just as confused as everybody else by the intrusion of pain, suffering and grief into our lives. And we are confused in all sorts of different ways.

At one end of the spectrum, there are churches who regard suffering as an aberration that has no place in the Christian life. The Christian life is seen as one of endless joy and victory, and if suffering comes, it is only for the purpose of providing an occasion to demonstrate God’s miraculous healing power. At its worst, if sickness or suffering doesn’t disappear in response to our prayers, the sufferer can be shunned as someone who is clearly sinful, unrepentant and failing to cooperate with God’s desire to heal them. Sometimes they are condemned for not having enough faith, despite the way we heard Jesus tonight making fun of the idea of faith being something that can be upsized (Luke 17:5-10).

At the other end of the spectrum, there are churches who almost seem to seek out suffering, out of some sort of misguided martyr complex. They seem to take a masochistic delight in suffering, as though it, in and of itself, proves them to be more worthy followers of Jesus. Jesus didn’t flee suffering, but neither did he seek it or revel in it.

Of course, suffering and grief don’t only come to individuals. They often comes on a mass scale and affect huge numbers of people. In major catastrophes, be they natural disasters or human-created horrors like war and systematic oppression, we encounter whole populations of people plunged into senseless suffering. Whether we are among the victims or watching on from a safe distance, Christian churches are still often confused, uncertain, and unsure how to respond to what is happening.

For the past six Sunday’s we have been hearing readings from the writings of the prophet Jeremiah, who is sometimes described as the suffering prophet or the weeping prophet. If you have been with us, you have probably picked up by now that Jeremiah was active in Judah in the early sixth century BC at a time when the Babylonian empire was brutally invading its neighbours, demolishing cities, raping and slaughtering the inhabitants, and carting the survivors off into exile.

Most of Jeremiah’s preaching career was warning the people of Judah and Jerusalem that their defeat by the Babylonians was now unavoidable. He was proved right, and in 587BC, after a siege that resulted in mass starvation and even cannibalism in Jerusalem, the city fell, thousands were killed, and most of those who were left were marched off to Babylon in chains. Despite Jeremiah’s warnings, the people were in shock and the suffering was immense.

Many of the defeated people of Jerusalem at that time were a bit like those churches that cannot comprehend any place for suffering in their lives or worldview. They had believed that they were God’s own people and that Jerusalem was God’s own city and therefore God would protect them and guarantee their safety. In our psalm tonight, we heard their bewildered cry: “By the rivers of Babylon we sat down and wept. How can we sing the Lord’s song in a foreign land?” In other words, how can we offer praise and worship to God when we have been dragged far away from the place where God lives and we have clearly been rejected and abandoned by God?

It is actually a psalm which, despite being made famous as a feel good pop song, ends in a very bad place. Some people manage to be ennobled by suffering, but this psalm gives voice to those who it reduces to bitterness, rage, and an unrestrained lust for vengeance, for payback. And so by the end of this psalm, we hear the writer virtually sounding a call to terrorism. He calls down blessings on anyone who pays back Babylon with the same sort of brutality, and even on those who seize Babylonians babies and smash them against the rocks.

Now I’m not condemning those who feel like that. In the face of suffering of that magnitude, such fury is completely understandable. Were I a victim of the nazi holocaust, or of the brutal destruction of Gaza today, I can’t be at all sure that that wouldn’t be me, seething with bitterness and rage and ready to commit the worst terrorist atrocities imaginable. But what we do know for sure is that Jesus responded to suffering in a very different way, and it is Jesus who we are seeking to follow.

Jeremiah can help us with the Jesus path too. Our first reading this evening was from the book of Lamentations, which was also written by Jeremiah and which is absolutely soaked in tears. It is a short book that consists of a series of songs or reflections that plumb the depths of pain and despair as Jeremiah surveys the utter devastation of the city he has loved all his life in the aftermath of the brutal Babylonian invasion. In the opening section that we heard tonight, Jeremiah depicts the city as a lonely widow, betrayed by her friends and weeping bitterly with no one to comfort her.

The book of Lamentations probably doesn’t tell us everything we need to know as followers of Jesus about how to understand and engage with suffering – we would need to go to Jesus for that – but it does lay down a good starting point that Jesus undoubtedly builds on. And I am going to focus on the lessons that arise from the example of this book this evening.

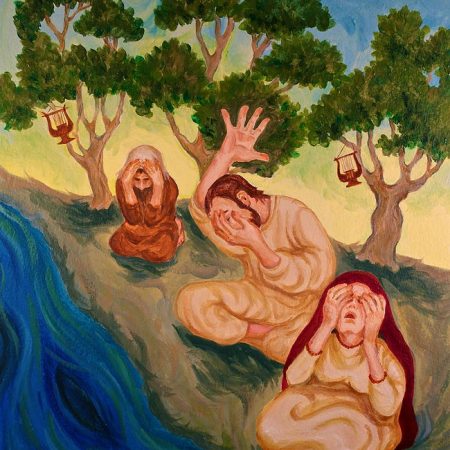

The primary example that the book of Lamentations sets for us, and it is a lesson that often terrifies us, is that a healthy response to pain and suffering begins with entering fully into it, allowing ourselves to feel the terrifying depths of it, and to weep freely and give voice to all the feelings that it awakens in us, the good, the bad, and the downright ugly. That, of course, is what the words lament and lamentation mean. Cries of pain, grief, distress, despair.

It is not just the words of the book of Lamentations that teach us about this, it is its unusual structure. As I said a minute ago, it consists of a series of five songs or poems. All but the last one have an acrostic form, which means that they are structured around the 22 letter Hebrew alphabet, with each poem having 22 stanzas, and each stanza starting with a word beginning with the next letter of the alphabet. The third poem is triply acrostic, with not only each stanza, but each line within the stanza starting with the relevant letter. And although the fifth poem is not strictly an acrostic, it still has 22 stanzas, and so it echoes the others.

Acrostics are very deliberate and methodical structures. They have nothing of the rawness or spontaneity that you might expect for an expression of pain and grief. Elsewhere, the acrostic structure seems to have been most often employed as an aid to memorisation, but that doesn’t really seem to be what is going on here. So what is going on here? Well, here in the book of Lamentations, the acrostic structure seems to be serving two purposes as it guides us in our encounter with profound suffering and grief.

Firstly, it tells us that as we enter into and explore our pain and grief, we should be very thorough; we should leave no stone unturned. The acrostic structure tells us not to skip anything. If you are going to do grief and lamentation properly, you’ve got to do the whole journey, from A to Z. Nothing is to be avoided.

If some people accuse you of wallowing in your pain and grief, ignore them. They are probably people who can’t bear to sit with pain and experience it fully. And as we know, if we try to suppress or brush aside our grief, our fears, our anguish, they never really go away. They just fester out of sight and gradually poison us. Much better to go all in like Jeremiah’s lamentations and explore them fully and meticulously, all the way from A to Z.

One of the reasons we are often afraid to do that, to let ourselves plunge headlong into the depths of our pain and grief, is that we are afraid that if we do, we might never emerge. We are afraid that we might never be able to find our way back to the surface and might just drown in our own tears. But that fear brings us to the second purpose that the acrostic structure seems to be serving here.

No matter how deep the acrostic poem takes you, you always know it has a beginning and an end. You always know that if you keep following it, you will reach the end of it. Even if you don’t know the alphabet of grief, if you know it is an alphabet, you know that it can’t go on forever. When you get to the end, you can go back and start again as Lamentations does for five cycles, but when you’ve gone back round a few times, you know yourself that you’re going back over work you’ve already done. The grief starts to lose its grip on you.

So the acrostic is a promise that pain and grief can be contained and survived. It is like a roadmap that assures us that what we are experiencing can be navigated and will come to an end. Things like our funeral liturgies do something similar. They enable us to enter more deeply into the experience of our anguish and grief because they promise to guide us or even carry us through the depths and back up to a safe conclusion.

One of the beautiful things about getting real about our pain and grief, and going all the way in, is that there is often a sweetness in grief. I know that some of you have experienced this as you have cared for a loved one in their dying and in the approach to it. Though it can be incredibly painful, there is often a rediscovery of just how deep the love between you is too. Those who get stuck in denial to desperately avoid the pain miss the sweetness too. These deep feelings resist being compartmentalised. You can only go deep by opening yourself to all the feelings, and so the deep grief and the deepest sweet love are encountered hand in hand.

Perhaps that partly explains how it is that learning to lament, learning to feel and express the depths of our grief, takes us so much closer to the heart of God. I don’t mean that God loves us more. It is more like what we mean when we talk of two people’s hearts becoming aligned with one another. The grief and heartbroken love that we hear expressed in Jeremiah’s lamentations echo the grief and heartbroken love of God’s engagement with our broken and destructive world.

This is the grief and heartbroken love that God feels:

– with every child or adult killed, maimed or traumatised in bombings;

– with every family crushed by breakdown or violence;

– with every ugly act of racism, sexism, or hostile nationalism;

– with every grove of trees bulldozed;

– with every species of plant or animal lost to extinction.

Because this is where God’s heart is, it is a journey we are also invited into, a journey into a deeper spirituality, a deeper engagement with life in all its fullness, all its profound depth and beauty. And the ways in are multitude. We simply need to pluck up the courage to stop avoiding grief and pain, to stop brushing it off lightly – Oh well, it’s just part of life; move on – and instead to go right in, to enter into the lament, to join our voices to the deep groans of creation and with the cries of lament that rise from a world in travail, aching for redemption.

That’s why these notes of lament are ever-present in our liturgy. Without them, our praise and thanksgiving is in danger of becoming delusional, becoming a form of happy clappy denial, papering over every crack of grief with a desperate pretence of feeling wonderful about everything.

Whether our next entry point is the sudden or gradual loss of a loved one, or the destruction of a native wetland we frequented as children, or the images on the TV news of children starving in Sudan or Gaza, or even the grief notes in our liturgy, it doesn’t matter. The invitation is there, and lamentation is one of the surest ways in. God is inviting us into a deeper and more honest engagement with reality, with God, and with the world God loves in all its beauty and brokenness.

The depth of lament is surely met by the sweetness of love for a person you are grieving.

Here is one of many great quotes from Walter Brueggemann on lament and grief: “The fact that Jesus weeps and that he is moved in spirit and troubled contrasts remarkably with the dominant culture. That is not the way of power, and it is scarcely the way among those who intend to maintain firm social control. But in [John 11:33-35] Jesus is engaged not in social control but in dismantling the power of death, and he does so by submitting himself to the pain and grief present in the situation, the very pain and grief that the dominant society must deny.”

― Walter Brueggemann, The Prophetic Imagination

Could I recommend that everyone download this sermon and share it with your friends (and enemies?).