A sermon on Matthew 2:16-18 by Nathan Nettleton

A video recording of the whole liturgy, including this sermon, is available here.

“A voice was heard in Ramah,

wailing and loud lamentation,

Rachel weeping for her children,

refusing to be consoled,

because they are dead.”

A Christmas scripture reading? Probably not one you will have heard at your local Carols by Candlelight event, but yes, it is one of the readings set for this Christmas. We heard it tonight in the middle of our gospel reading, but Matthew’s gospel was quoting it from the prophet Jeremiah (31:15). It always sounds a jarring note when it comes up on the first Sunday of the Christmas Season. Some years, that means it’s on Boxing Day when our houses are still strewn with wrapping paper, and it’s like a Christmas car crash, a sudden brutal slam back into the grim realities of a broken world.

This year though, we in Australia were brutally slammed back into the grim realities before we even got to Christmas Day.

“A voice was heard at Bondi Beach,

wailing and loud lamentation,

Rachel weeping for her children,

refusing to be consoled,

because they are dead.”

At many events like the big Carols by Candlelight at the Myer Music Bowl, there has been acknowledgement of the tragedy at Bondi, but it’s been a bit awkward. What they seem to have been saying is, “We know that what happened is too big and too awful to ignore and not mention, but it really doesn’t fit with what we are on about here, so we’ll acknowledge it before we get underway, get it over and done with, and then get on with being as obliviously happy as we can possibly be.”

That’s understandable. I’m not pretending for even a moment that the Christmas being celebrated at those events is the same thing as what the churches call Christmas. The two only even overlap by one day, and the Santafest one is now done and dusted while we’re not even half way through our twelve days. So I’m not here to tell mainstream society what their event should mean.

But for us here in the Church, as we journey through this Christmas season, the encounter with this Bible reading on this Sunday is telling us something hugely important about what our celebration of Christmas means.

“A voice was heard in Ramah,

a voice was heard at Bondi Beach,

wailing and loud lamentation,

Rachel weeping for her children,

refusing to be consoled,

because they are dead.”

One of the reasons we struggle to recognise how this story fits with the good news of God come among us as a tiny baby is that we have the enormous privilege of living in a time and place where babies are mostly born into peace, health, prosperity, and safety. In much of the world, and through much of history, that has seldom been the case. More often than not, even those children who are born safely arrive in contexts where the parents have every reason to fear for their survival. And if the message of Christmas is to be good news at all, it has to be good news in all those contexts, not just ours.

It has to be good news in Ramah, in Bondi, in Gaza, in Ukraine, in Darfur, in Myanmar.

When the prophet Jeremiah first wrote these words about Rachel’s voice of agonised lament being heard in Ramah, it was already a similar move to my linking of it with Bondi. Jeremiah was writing many generations after Rachel’s time, and his words didn’t refer to any literal event in her life. Rachel was seen symbolically as the mother of Israel, and so Jeremiah describes her as weeping inconsolably as her children, her descendants, are chained and marched off to exile in Babylon. Ramah, which was not far from Rachel’s burial place, seems to have been the staging post where the convoys of exiles were assembled before being marched off.

“A voice was heard in Ramah,

wailing and loud lamentation,

Rachel weeping for her children,

refusing to be consoled,

because they are gone.”

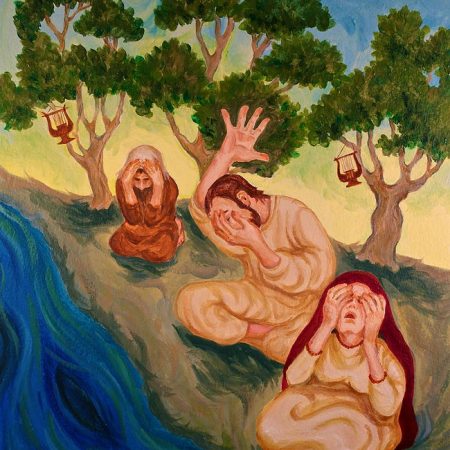

When Matthew re-quotes Jeremiah’s words in his gospel account that we heard tonight, it is in the midst of the Christmas story and in response to a new act of unspeakable violence and terror. King Herod, who was well known for acts of unspeakable violence, sends a death squad into Bethlehem to kill every child under the age of two, just in case one of them grew up to fulfil an old prophesy and become a rival to his rule. And you can bet that such a death squad was not checking birth dates or genders. Children were just slaughtered indiscriminately, as were any parents who tried to get in the way. That’s why it is so similar to what happened at Bondi: it was a hate crime, indiscriminate slaughter based on mindless hate.

And of course, Bondi is far from the first massacre in Australia. Speak to Uncle Den, or to any of your indigenous friends. Much of modern Australia was built on countless massacres of first nations peoples. They have no trouble hearing and recognising their reality in these words.

“A voice was heard in Ramah, in Bethlehem, in Bondi,

in the back blocks of Australia, just out of sight,

wailing and loud lamentation,

Rachel weeping for her children,

refusing to be consoled,

because they are dead.”

So where is the good news in any of this? How does the Christmas message shine any light into the inexplicable darkness of such horrors? Clearly the Christmas message is not that such things will not happen any more, or that anyone can expect any kind of supernatural protection when they do. The shadow of death that Jesus barely escapes as a newborn catches up with him in a tortured execution before he reaches middle age.

So if it’s not safety, protection, or escape, where is the good news in any of this? Let me identify two things.

Firstly, and if this is not good news in itself it is at least a necessary precursor to good news, there is a promise to those in unbearable pain that they are seen, that they are not forgotten or erased, but that they are seen and heard and understood.

You might have noticed how often this idea has come up in discussions of what happened at Bondi, and of how people can best express care for their Jewish friends in the aftermath. The experts on trauma and grief speak of the importance of being seen, of knowing that people are not turning their faces away. We don’t have to have the right words to say, or to be able to offer explanations or magic words that make the pain go away. Just letting people know that their pain and trauma are seen, recognised, and honoured makes an enormous difference.

So the regular retelling of this story of terror and trauma as part of our Christmas stories tells those who are suffering that God is not looking away, and that God’s people (at least if they have grasped their own tradition) will not look away. This story is calling us and teaching us to be people who do not look away, and who do not just do that awkward acknowledgement so that we can move on as quickly as possible with pretending the world is a lovely joyous place. We are to be, at the very least, a people who can say to the sufferers, “We see you. We honour your pain. And we will not try to hurry your grieving to make ourselves feel better. God is with you, and we are with you.”

“A voice is heard, truly heard and honoured,

in Ramah, in Bethlehem, in Bondi,

in the back blocks of Australia, just out of sight,

wailing and loud lamentation,

Rachel weeping for her children,

refusing to be consoled,

because they are dead.”

Unfortunately, this lesson is only going to become more and more important to us, and more and more essential to what it will mean to be followers of Jesus in the world. As Bondi reminds us, even relatively peaceful and stable societies like Australia are becoming more polarised and hostile. Intolerance and hatred might not become the norm, but they are becoming more prevalent, and it only takes one or two people fuelled by puritanical hatred to create a massacre. And as the climate catastrophe plunges more and more of the world into fear and desperation, we will be called on more and more to see, to hear, and to lead the way in responding with love and compassion and grace instead of blame and escalating insanity.

There’s a second way in which this story speaks good news into the deep darkness of horrendous suffering. It tells us that God doesn’t stop at the necessary seeing and understanding, but that in taking on human flesh and coming among us, God has put his body on the line to take the full force of the world’s hatred and hostility.

The forces of death that inflicted such horror in their pursuit of the infant Jesus in Bethlehem continued to stalk him throughout his life, but they couldn’t intimidate him into pulling his head in and leaving others alone and unprotected to preserve his own skin. Though his parents might have fled in search of safety with him in this early story, once he was responsible for his own choices, he stood his ground, resolutely maintaining the dangerous and unpopular love for all that so enraged angry and divisive minds. And most extraordinarily, as hatred and death closed in on him and did its worst, he absorbed it all without ever reciprocating it, or seeking to have anyone made to pay.

And it is precisely in that, in forging a path of unquenchable grace that does not retaliate or escalate the hostility, that Jesus opens a pathway to salvation and calls the world to follow. It is not a salvation that ensures that hate crimes or other disasters won’t happen, but it is a salvation that offers a pathway through them that will emerge in a place of new life. Indeed, it is a pathway that leads from the screams and inconsolable lament of Bethlehem, to the agonising horror and gasped words of forgiveness at the cross on Golgotha, before it finally rises in resurrection where the full astonishing force of forgiveness and grace and love is vindicated and poured out for all the world.

We don’t have to look far to know that suffering has not been ended. But in this story, and in the way it continues to unfold, we know that suffering is no longer either erased or meaningless, but is now a window into the heart of God calling the world to rise to life and grace in all its fullness.