A sermon on 2 Corinthians 5:16-21 & Luke 15:1-3, 11b-32 by Nathan Nettleton

A video recording of the whole liturgy, including this sermon, is available here.

In most of the trouble spots around the world, there are people putting in a lot of effort behind the scenes trying to hammer out the details of cease-fires and peace treaties. Even when they are successful, they seldom get much credit for their work; the credit usually goes to the respective leaders for whom they have acted. You can probably name the presidents of Russia and Ukraine, but probably not a single one of the negotiators working for them trying to find a pathway to peace that both can agree on.

Frequently, to everyone else, their work seems far too slow: as the bombs continue to fly, all we get are dribs and drabs in news reports about how the peace negotiations are grinding on with a final agreement still not reached. But without these people, and their diligent work, the world would be an even more fraught and dangerous place than it already is.

In most cases, the peace negotiators’ job involves trying to piece together a patchwork of compromises such that each side gives up enough of what they were asking for to secure the end of hostilities. For example, Ukraine has already offered to commit to never joining NATO. But you don’t want the agreement to involve giving up so much that either side loses face and are left even more bitter and hostile. World War 2 was in part caused by the humiliating conditions imposed on Germany at the end of World War 1, and at least some of Russia’s current aggression has probably been exacerbated by the gloating behaviour of the West at the end of the Cold War.

If the peace negotiators can succeed in piecing together a suitably balanced patchwork of compromises, so that both sides can agree to accept it, then an end to the violent hostility can be secured, and the work of building a lasting reconciliation can begin. In most cases, some of the onlookers will not be altogether happy with some of what was given away – perhaps some monster was guaranteed immunity from prosecution for past crimes – but often the only real alternatives are either to give these things away or to let the bloodshed continue.

According to the Apostle Paul, in the reading we heard from his letter to the Corinthian churches, God has hammered out a peace agreement with the world, and has made some astonishingly big concessions in the process. Indeed God has made exactly the sort of concessions that often cause angst in peace agreements; most notably offering all of us, the worst of us as well as the best of us, immunity from prosecution. In fact, if you put the agreement that God offers on the table next to some of the convoluted cease-fires and treaties that are painstakingly negotiated between hostile nations, you might start to wonder what was in it for God.

You might be tempted to describe it as an almost complete capitulation by God. God seems to give up everything, offer everything, and demand almost nothing in return. In particular God promises to wipe the record of everything we’ve ever done wrong and hold nothing against us. And as if such a complete immunity from prosecution was not enough, God also offers us high-ranking jobs as his ambassadors to represent him in the ongoing task of promoting the agreement. It is a bit like the USA opening its negotiations with ISIS by offering its leader immunity from prosecution and a new job as the American Secretary of State.

I don’t think any of us could imagine any of the world’s superpowers ever making such a monumental capitulation. Such a capitulation might sometimes be able to be extracted from a very guilty party who has been single-handedly responsible for the mess, but in the case of the reconciliation deal which God offers to the world, the one who clearly holds the moral high ground is the one rolling over and conceding everything.

We are the one’s who took God’s gift of a beautiful planet and set about polluting it, and tearing it apart by war, hatred and injustice. We are the ones who were invited to live in peaceful communion with one another and who instead hardened our hearts and succumbed to the demons of selfishness, greed and cynicism. We are the ones who squandered our gifts, blew our inheritance, and dragged our own names and God’s through the mud. So what is God doing making such enormous concessions to secure a peace agreement with us?

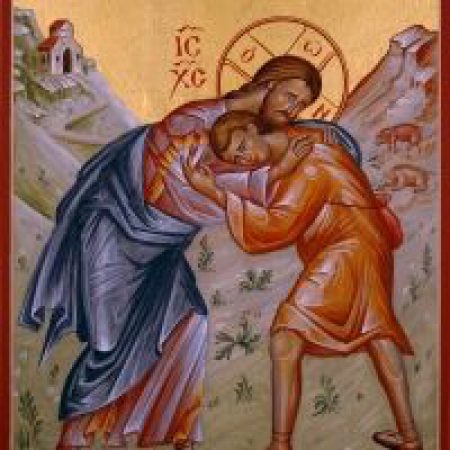

On the micro scale, you can hear this same scenario being played out in the story Jesus told about the prodigal son, the story we heard earlier.

The prodigal knows he’s got no bargaining power. He has blown his father’s trust and money, and dragged his father’s name through the mud of the pig sty. And he is desperate. He is ready and willing to give up everything for whatever shreds of his father’s care might be forthcoming.

But instead it almost becomes a competition to see who can give up the most. The ageing father bounds down the street in a most undignified manner, throws himself on his errant son, forgives him everything, and then crowns him in glory and throws a huge welcome-home party for him.

What more could God give? Well actually, says the Apostle Paul, there is more. Reputation. God was in Christ, trading reputations with us. Christ, who was not implicated in any wrongdoing, accepted guilt by association with us. Christ put his hand up and implicated himself in our callousness, injustice and hostility. He put his reputation on the table along with everything else to secure the deal. And, says the Apostle, in doing so he paved the way for us to be implicated in his goodness, for us to receive righteousness by association.

Again you can see this illustrated in the story of the prodigal son. In that culture, as in many, the behaviour of the son is seen as reflecting directly on the parents, and this is one of the things that gives rise to so-called honour killings in some such societies.

Indeed, in a passage that is almost certainly being alluded to in the prodigal son story, Deuteronomy 21 mandates death by public stoning for a son who disgraces his parents by rebellious, gluttonous, drunken and disobedient behaviour. The surrounding culture was not going to commend and congratulate this father for his generous forgiveness. They were going to see him as failing to fulfil his legal and moral obligations, and they would now regard him as the same sort of moral reprobate as his disgraced son.

The father is effectively swapping reputations with his humiliated son. And in holding this up as a picture of the love and mercy of God, Jesus is completely upending the accepted image of a stern and removed God who demands that a price be paid for every sin before there can be any pardon.

No wonder the Apostle Paul says we’d be mad to turn our backs on this peace deal that God is offering. It’s a take it or leave it deal, but why on earth would you leave it? We’ve got everything to gain and almost nothing to lose. The deal is completely stacked in our favour. We are offered complete forgiveness of sin, reconciliation with God, a new identity, a fresh start, mercy and healing and life and love beyond our wildest imaginings.

And what are we asked in return? What do we have to put on the table to complete the deal? Well, there’s a paradox here, because the answer is both nothing and everything. God actually demands nothing of us except our willingness to accept the deal, to sign our names on the line. Everything else is completely voluntary. God signs off on the deal regardless of our response. It is sheer gift. There is nothing you can do to undo God’s gracious acceptance of you. God will be all over you like the prodigal’s father, lavishing love and generous gifts on you. And it costs you nothing at all.

And yet the paradox is that if you give nothing in return you will probably fail to appreciate and enjoy even the lavish gifts you are given. You can end up as sad and twisted as the prodigal’s older brother who is now the sole heir to all his father owns, but stumbles around weighed down like a slave by yesterday’s angers and resentments. You can be forgiven and still feel burdened by guilt. You can be accepted and still exclude yourself. You can be loved and still feel yourself unlovable.

It is easy for us to fall into taking sides in the story of the prodigal. We tend to identify with one or the other brother and to judge the other. We can easily look down on the younger brother for his callousness and irresponsibility, and we can easily condemn the elder brother for his self-righteousness and his insensitivity to his father. But disappearing down either of those paths misses the point and cripples our own capacity for love and celebration.

The prodigal’s father does neither of these things, and it is his example that Jesus is calling us to follow. He does not berate the younger son for leaving and wasting everything, and neither does he chastise his elder son for being such stuck-up sourpuss. He just invites both of them to the party, to an all-welcome celebration, where reputations are forgotten and only forgiveness and unconditional love matter. Can we rise to the challenge of the prodigal father and renounce our irresponsibility and our self-righteousness?

In this season of Lent we are reminded again and again of the discipline and commitment required to experience the full fruits of life’s greatest gifts. They are gifts, and our response is purely voluntary, but unless we do volunteer and respond in full, the gift may again be squandered and we may again short-change ourselves horribly.

God calls us to become ambassadors for Christ, to be the ones who take the news of God’s gracious reconciliation and proclaim it and live it out to the full so that the full dimensions of God’s gracious love might be readily apparent for all the world to see. God’s offer of peace and reconciliation is not dependent on our acceptance of that call, but those of us who don’t accept it will probably find that we are cutting off our noses to spite our faces by depriving ourselves of the here and now benefits of that gracious and healing love. They will still be there for us, but we may make ourselves the last to know it as we stand stubbornly and miserably outside the party.

So as extravagantly free and generous as God’s gift of reconciliation is, let us respond to the challenge of this Lenten season by committing ourselves to the way of Jesus, to the way of disciplined love and scandalous mercy that leads all the way to the cross and beyond, and which in its very willingness to give up everything, opens our hands and our hearts to receive the fullness of life and love and peace that we hunger for with every fibre of our being.

Perhaps that’s precisely the method in God’s madness. Perhaps that’s the secret God is enjoying and trying to let us in on: that only in putting everything we are and everything we have on the table and letting it go that we free ourselves to enter the party and know the fullness of life and love for which we were created.

Nathan’s sermon is full of good news for us. Luke’s text is the story form of Paul’s narrative in his Second letter to the Corinthians. Both herald our righteousness derived from faith in Jesus as Son of God.

What Nathan says about the texts as applying to us individually is wonderfully expressed in his modern metaphors. Nathan also explains that we should be careful not to decline the invitation despite its obvious benefits.

But here i think hides the more important message in the texts despite being in full sight on the page.

We are blind to it because we read the texts as contemporary Western minds rather than Torah abiding Jews. These Torah abiding Jews believe they already have reconciliation with God – the rules are clearly defined in the Torah which comes from Moses who talked with God as with a friend. Jesus had been condemned by the Jewish leaders and hung on a tree by the Romans. According to the Old Testament texts Jesus was cursed.

Over against this logic is the fact that the Corinthian readers are Gentiles and Luke’s Gospel is focussed on drawing Gentiles in. Both claim that Jesus is superior to the Torah in the light of the Resurrection. There was disagreement not just between Christians and Jews but there was major disagreement between Paul’s practices in Antioch and other diaspora territories and the leaders of the Christian mission based in Jerusalem. The Jerusalem based leaders were more closely aligned with Torah observance and Paul in his letters to the Galatians, especially, sets out a major debate about there being no need for circumcision for gentile converts. Jesus has been declared just and righteous through resurrection.

Paul and Luke consider they are themselves equally as interested in Love and Law as the Torah abiding Jews and those same Torah abiding Jews consider they themselves are both Law abiding and promoters of Love. What we might consider Jewish hard heartedness is on the Jewish perspective seen as judicious discipline and structure that protects love. That is why Jesus claims not to abrogate the Law but to Fulfill it.

So the texts we are considering belong to “interpretation” – is Jesus, and Paul as his ambassador, being disloyal to their Jewish roots or not?.

As demonstrated in Paul’s Galatian letter, this underlying difference of outlook was not just about who was good and who was bad – it went to the whole meaning of Jewish history since the promise to Abraham. The Torah came via Moses myriads of years after the promise to Abraham. Hence we see in Luke’s Book of Acts the significance of Stephen’s great speech about Faith in Chapter 7; a speech no doubt mirroring Paul’s Letters, written decades earlier, about Faith. If Abraham pre-dated the Torah, why, ask Paul and Luke, can Christians not get behind Torah to a deeper reality?

So that portion of Paul’s Letter to the Corinthian Church that we are focussing on this week is really about how Paul as Jesus’ ambassador, with his message of relief for Gentiles from Torah statutes such as circumcision., is in righteousness of God. Paul’s life is in his ministry, a ministry of reconciliation emanating from faith in Jesus. Paul’s Damascus road experience, of a Jesus who is alive, is vital to that faith. It seems to me that maybe that the resurrection means that God justifies Jesus such that for Paul we too are justified by God if we have Faith in Jesus. I wonder if this is Paul’s meaning behind a phrase such as – justification through faith.

Luke parallels Paul in a story that variously is titled – Prodigal Younger Son; Forgiving Father; Obstinate Elder Son. The language of the Lucan story is clear enough in its mutiple use of Torah language and images – clearly to a Torah servant the Father is as “prodigal” as the Younger Son. An the Elder Son is quick to point out this character flaw in his Father. As Nathan pointed out in his sermon -The Father had transgressed the Torah principles applying to Fatherhood and Children. He had “divided his property (- being)” simply based upon a demand from the younger son. The Younger Son “gathered” his share in, went to a “far country” and “scattered widely without saving anything”. He worked with pigs and no-one gave anything to “him”. Finally The Younger Son returns, “having come to himself”. he admits to being a sinner – hamartia -not a “transgressor” as the Elder Son describes – as one who breaks the “commandments” – like his Father. Sinning is a fault; transgression is a refusal to bear the “yoke of the Law- it is rebellion. Both Father and Younger Son seem to be transgressors in the plot. But then the Younger Son asked the Father “to make him AS one of the hired servants”. The Father could NOT make a Son into a hired servant. Clearly this is the centre piece of Luke’s story – one can even transgress the Law but one cannot rebel against status of Father and Son. The Father/Son relationship is permanent, indelible.

Luke emphasises the “transgressive” nature of the Father through what is a repeat of the dialogue between Younger Son and Father – the dialogue of Father and Elder Son. The whole response of the Father is to place the Elder Son in control of the dialogue. The Father is consistent – a Son is a Son – Younger or Elder. The Father is divided – his being ( greek ‘ousia’ = property) is divided – not yet physically dead, the father is now alive only in His Sons. He has given totally. No wonder a Torah abiding Jew would hear this story as a mockery of the Christian position.

However for Luke, as for Paul, the Resurrection changes everything. Luke’s Story does not resolve anything – certainly the immediately preceding stories of the finding of the Lost Sheep and the finding of the Lost Coin play totally into the theme of the finding of the Lost Son. But clearly the father has to take some responsibility for the Lost Son. Sheep and Coins lose themselves – not Sons!! Sheep and coins anonymously become lost – the Younger Son was aided and abetted by the Father in getting lost. The Elder Son – the “dramatis personae” of the Pharisees and Scribes – make that perfectly clear! Paul and Luke provide another resolution to the apparent victory of the Torah stance – for Paul it is the Cross in the light of the Resurrection; for Luke it is The Ascension; an open heaven for the Son – Father God does not abrogate a Son – Faith in Jesus makes us Sons of God. No one can sideline God – we may not understand God but we cannot transgress allegiance to God. The Torah is NOT God – it is an “overshadowing” to use Lucan terminology but not the substance of God – Paul and Luke are ‘singing from the same song-sheet” – Abraham lived through Faith – so must we- even if it looks a faith in a God who lacks Torah “justice”.