A sermon on the book of Ruth, by Nathan Nettleton

A video recording of the whole liturgy, including this sermon, is available here.

On a first reading, the book of Ruth seems to be about the most tame and inoffensive book in the whole Bible. Set in the early period of Israel’s history, before the time of the first King, it is just a delightful little romance novel. Or is it? Sometimes a seemingly idyllic story can have a powerful sting in the tail – it all depends what else is going on at the time it is told. If you’ve been a regular at Matins over the past week and a half, you’ve heard the whole story read, but if that’s not you, then I recommend that you sit down and read Ruth straight through sometime (perhaps before reading any more of this). It’s only about 3 or 4 pages long.

You probably won’t spot any sign of any angry politics or fiery debates there. But perhaps that’s just because we’re not hearing it in the social and political context it was first told in. Linguistic studies have enabled us to be fairly sure that although the story is set early in Israel’s history, it was written down in its final form much later, after the Babylonian exile and during the time of Ezra and Nehemiah.

So let’s turn to the books of Ezra and Nehemiah and see what was going at that time. (Pick up your Bible again, and read Ezra 9:1 – 10:5 and Nehemiah 13:23-27.)

Nehemiah says:

In those days also I saw Jews who had married women of Ashdod, Ammon, and Moab; and half of their children spoke the language of Ashdod, and they could not speak the language of Judah, but spoke the language of various peoples. And I contended with them and cursed them … and I made them take an oath in the name of God, saying, “You shall not give your daughters to their sons, or take their daughters for your sons or for yourselves.”

In Ezra it says that some people came to the priest Ezra with a similar report, saying:

“The people of Israel, the priests, and the Levites have not separated themselves from the peoples of the lands with their abominations, from the Canaanites, the Hittites, … the Moabites, etc. For they have taken some of their daughters as wives for themselves and for their sons. Thus the holy seed has mixed itself with the peoples of the lands.”

So Ezra threw himself down weeping before the house of God, and the people also wept bitterly. Then Ezra stood up and made the people swear an oath saying, “We have broken faith with our God and have married foreign women from the peoples of the land, but even now there is hope for Israel in spite of this. So now let us make a covenant with our God to send away all these wives and their children.”

All of a sudden, the book of Ruth, our pleasant little romance novel about the lovely Moabite girl who marries a fine upstanding Jewish man doesn’t look quite so cute and uncontroversial does it? All of a sudden we have a serious clash of ideologies; a clash of opinions on the nature of the faithful community and the pure people of God.

How did such a clash come about? Let’s take a lightening trip through the history of Israelite self-understanding to see. When Moses and the people arrived in the promised land after escaping from slavery in Egypt, they were more a confederation of tribes than a unified nation. There is a fair bit of evidence to suggest that what became the nation of Israel under the first kings, Saul and David, was a broad confederation of descendants of Jacob coming from Egypt and various other tribes that joined them along the way.

Although the idea of being descendants of Jacob remained dominant, it was a bit like the way we Australians talk about being descended from the convicts when really we are a mix of the descendants of the convicts and lots and lots of other groups. They gradually merged their various tribal identities into one larger concept of nationhood much the same way we have.

Now in that early stage, no doubt partly because they were so multicultural anyway, the faith of Israel was very inclusive. If you read the laws of Moses you will find that there are clear laws requiring Israelites to ensure the welfare of the poor, the widows and the asylum seekers. The law required that where a non-Israelite sought to join themselves to Israelite society and faith, their rights became almost exactly the same as that of the native Israelite.

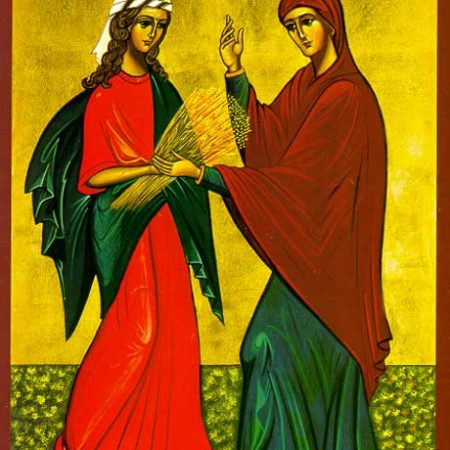

Some of the early laws of this period can be seen depicted in the book of Ruth. There was a law that said that when you harvested your grain you couldn’t go back and pick up the dropped bits (Deuteronomy 24:17-22). Instead you had to allow the poor, the widows and the resident asylum seekers to pick up after you. They didn’t have their own land and so this law ensured that they had access to the fruits of the land. In Ruth 2 we see Ruth following the workers in the field belonging to Boaz. Ruth, being a poor foreign widow, represents all three groups.

There was also a custom called “Levarite marriage” that said that if a man died leaving no sons, his nearest male relative was expected to marry his widow, and the first son born would count as the son of the dead man. This law (Genesis 38:1-8 & Deuteronomy 25:5-10) safeguarded the welfare of the widow and any other children she might have. This custom too is described in Ruth. Naomi speaks of Boaz’s responsibilities, as a close kinsman, to care for them and to marry Ruth. Boaz points out that there is a nearer kinsman and so he has to clear it with him before he can marry Ruth, but the assumption is that someone is responsible to marry her to ensure her welfare. Rather than marrying Ruth the Moabite being a moral outrage in the way Ezra and Nehemiah saw it, it was understood as a faithful covenant duty.

The whole vision of Israelite faith in that era was welcoming and inclusive and called for a radical responsibility by the whole community to ensure the welfare of those who might otherwise be pushed to the margins of the community.

Unfortunately there is a tendency in human beings to always want to narrow down the in-group and write off those who don’t fit, and to narrow the view of God’s concerns accordingly. This was somewhat understandable in Israel’s history. They were a small nation in a strategic location surrounded by big powerful nations. Their existence was always under threat and they were taken off into exile more than once. When you are a persecuted minority group, drawing more and more clearly the boundary lines of who is and isn’t part of your group is a basic survival strategy.

By the time of Ezra and Nehemiah, after periods of exile in Assyria and Babylon and now under Persian domination, the focus of Israelite faith and self-understanding has narrowed down to the pure “holy seed” of Judah. The holy seed is to be protected at all costs from any danger of contamination because God’s covenant is only with the holy seed. The idea that God even cared about the fate of those outside the holy community had all but vanished from the dominant ideology.

Israel no longer saw itself as a light to the nations, but as a pure light to be protected from the nations. The generous inclusivity of the early faith was a suppressed memory. Instead of their faith and law having a clear focus on protecting the welfare of those on the margins of the community, the focus is now on protecting the identity of those at the core of the community, even if that must be done at the expense of those on the margins.

In the time of Ezra and Nehemiah, Israel had achieved a reasonable level of autonomy under their Persian overlords, and the Zadokite Priests, of whom Ezra was one, were the effective leaders of Israelite society. The books of Chronicles and Ezra and Nehemiah portray the world through their eyes and show this great concern for a clearly defined pure community, keeping itself rigorously separate from all that is foreign. The most extreme and horrible expression of this obsession was the compulsory divorce of foreign wives and the exiling of them and their children. Imagine the trauma and needless suffering this would have caused as families were torn apart and women and children left destitute, all in the name of religious zeal.

In the books of Ruth, Joel and Jonah, which all come from this same period, we have evidence that the Zadokite priests with their policy of ethnic cleansing did not have things all their own way. Dissenting voices were raised, and those dissenting voices were able to point to the ancient law of the early Israelite community to urge a return to an earlier more inclusive vision of what it meant for the community to be faithful to God.

Seen against this background, this lovely little romance novel becomes a radical critique of a dominant social vision, and a clarion call to an alternative vision of faithfulness. Ruth was a Moabite woman, one of the nationalities specifically mentioned in Ezra 9:1 and Nehemiah 13:23, and as Jude told us last week, a nationality generally regarded as the scum of the earth.

But the romance novelist portrays her as being more faithful than seven Jewish sons and, in the guise of this idyllic story, spells out how the early Jewish laws of justice and welfare applied equally to foreigners such as her. Thus a Moabite woman is portrayed as the ideal “Jewish” wife and the law is shown to not only accept her marriage to a Jewish man, but command another Jewish man to marry her when she is widowed without sons. And to cap it all off, the story ends by telling us that from the offspring of this “foreign wife” comes the all-time great Jewish hero, King David. Take that Ezra and Nehemiah; your policy would have meant deporting King David’s great-grandma!

In the face of this policy of ethnic cleansing and compulsory divorce, we hear the alternative view put into the mouth of Boaz when he answers Ruth’s question about why he would be kind to her, a foreigner, by pointing to her faithfulness and saying, “May the LORD reward you for your deeds, and may you have a full reward from the LORD, the God of Israel, under whose wings you have come for refuge!”

So the way this earlier vision understood purity then was that the important thing was the purity of what people do rather than the purity of their origins. Matthew’s gospel has a similar emphasis in the genealogy of Jesus at the start of his gospel. He lists all the fathers, but mentions just five mothers – Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, Bathsheba, and Mary. All five were either foreigners, or had some shadow of sexual scandal hanging over their heads, or both. So even the purity of the Messiah is not about the ethnic or moral purity of his origins. As Martin Luther King jr went on to put it, the dream is of a day when all people will be judged not by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character.

Well, it’s all very well to see how radical the book of Ruth was in the fourth century b.c.e. The big question for us though is what are we to make of its message in our context nearly two and a half millennia later.

What vision are we going to champion when churches talk of protecting the purity of their witness by forcing out the gays or the transgender people? What vision are we going to champion when our governments, having proven during the pandemic that they are quite capable of providing housing for the homeless if they want to, now cut back housing and welfare services to those who have no one else to protect their interests?

What vision are we going to champion when our society demonises and separates off those who come seeking refuge “under our wings” but had no way of getting official documentation before arriving here? What are we going to say when our government keeps 46 refugees and asylum seekers locked up in the Park Hotel in Carlton, month after month after month, and denies them even basic support as part of the government’s overall deterrence policy? They certainly aren’t being invited to glean our fields under the policies of this government.

What vision are we going to champion when our nation still fails to take seriously the trauma suffered by indigenous people whose families were compulsorily torn apart and children removed under assimilation policies that were taking place with the lifetime of most of us but which sound eerily Ezra-like in their passion to ensure the purity of white civilisation?

What vision are we going to champion? What vision of the faithful community will we raise our voices for?

Of course, there are white supremacists and ultra-right nationalists who are very fond of arguing that the Bible supports their views of the importance of maintaining racial purity, violently if need be. And read selectively, they are right. Ezra, Nehemiah and Chronicles certainly argue that way, although it is bizarre that the people who are so positive about those parts of the Bible now are also anti-semitic. But what we have in the Bible is a sustained argument that was going on among the people of Israel, and our little Romance novel of Ruth is part of the other side. So the question for us is not whether a view can be found in the Bible, but which line of thinking finds its way all the way to Jesus. And when it comes to Jesus, not only are we told that Ruth herself was one of Jesus’s ancestors, but we find Jesus arguing over and over against the oppressive use of concepts of religious and national purity.

So what vision are we going to champion? What vision of the faithful community will we seek? We will follow the line that runs through this lovely romance novel and finds its ultimate champion in Jesus, and however unpopular it might be, we will stand for radical welcome and hospitality for all who seek refuge under our wings.

Thank you for this amazing insight into this story – how it would strengthen the heart of the outsider and the stranger to discover that they are welcomed and included. Dr Thorwald Lorenzen said of parables – that they were a good story, but also a story that one might find ones self in and then be changed by the story. The Ruth story is one such story.

Nathan’s richly embroidered tapestry of biblical texts and their historical meanings demonstrates how impoverished the New Testament Church has been over centuries as we ignored Old Testament experiences of God’s Spirit working amongst humanity. How narrow we became as rivalry clouded inspiration. Within my Catholic tradition there is a desperate vitriol burdened by beliefs and practices that arose from a narrow concept of the History of Revelation. God must truly be frustrated that we can so easliy ignore so much of His Word and then to add insult to injury we claim to interpose our own re-write of His Script. It is hard for all of us to “un-learn” messages that have been given to us by loving parents, grandparents and hard working clerics and religious and lay family and friends. Loyalty is such a great tool in the right place but also such a “widow-maker” of fruitful ideas in the wrong place. Nathan’s comments about various current social evils in society do not all fit my paradigm and so we all continue to consult and dialogue for the revelation of truth. Whatever about these shortfalls, his sermon has certainly cleared away a lot of hurdles that have been preventing life from flourishing in our baptismal callings.