A sermon on Jeremiah 23: 1-6 & Luke 23: 33-43 by Nathan Nettleton

A video recording of the whole liturgy, including this sermon, is available here.

Today is the last Sunday before the season of Advent, and it is designated in the Church’s calendar as the Feast of Christ the King. The behaviour of some of the leaders of the world’s most powerful nations in recent years has raised all sorts of questions for many of us about the nature of true leaders, and in such a context, naming Christ as our king or president or prime minister is not without significance.

You may have noticed that some of the big protest rallies against Donald Trump’s leadership and policies have been dubbed “no kings” rallies. People are alleging that Donald Trump is behaving not as a president, but as though he was intent on ruling like a king, and they don’t want a king.

Unlike presidents, kings don’t get elected at all, and certainly Donald Trump has suggested in the past that once they elect him, the American people wouldn’t need to vote again. On the other hand, given that he did get elected, some of the people who most dislike him might be feeling a bit of renewed nostalgia for a benign hereditary monarchy.

Because Queen Elizabeth II reigned for over seventy years, King Charles still seems like a new king, even after more than three years now, and we are still getting used to the idea of having a king again. Expectations of him were pretty low, but I think he has handled the role better than many people feared.

But however much we may like or admire particular members of the royal family, and however much we may enjoy the pomp and ceremony of royal gala occasions, weddings and the like, the British class system that they sit at the top of is in principle exactly the same as the Indian caste system which pretty much everyone I know finds abhorrent. And perhaps the fact that the new king has had to deal with his brother’s infamy by stripping him of his titles and property can serve to remind us of the abomination of a class system which gave him those titles in the first place.

So what is this Feast of the Christ the King and does it shed any light on our understanding of our relationship to those who wield power in our world. The history of this feast reveals it to be a strange insertion into the calendar, but its very strangeness has an ironic power that does much to bring its meaning to light and to justify its continuing observance.

It’s history is a very short one. The Feast of Christ the King was created, with no prior tradition, exactly one hundred years ago, by Pope Pius XI. Pius was negotiating the Lateran Treaties with Mussolini to sure up the political status and independence of the Vatican. As part of the deal, the Vatican took action to suppress the only democratic party in Italy. Pius was no lover of democracy. He preferred monarchies and authoritarian regimes because he could negotiate treaties with them which favoured the Roman church. Both Mussolini and Hitler granted the Roman church wide-ranging favours in exchange for political silence.

The Feast of Christ the King was, therefore, created with a political agenda, to sure up the Vatican’s power and the power of those regimes with whom the Vatican had negotiated expedient cooperative arrangements. It was to do this by reinforcing the message that the Church wanted obedient subjects and that the Kingship of Christ was to be envisaged in terms of an absolute European monarch. Thus we now have the anomaly of a feast in our calendar which arose out of a devil’s pact between the Church and the Fascists! So why on earth would we continue to observe it?

Well, sometimes these sort of underhand attempts to forge a political compromise between the Church and the governing regimes of the day have an ironic absurdity that is actually very helpful to us in seeking to understand the irony with which Christians have traditionally used the term “king” when speaking of Jesus.

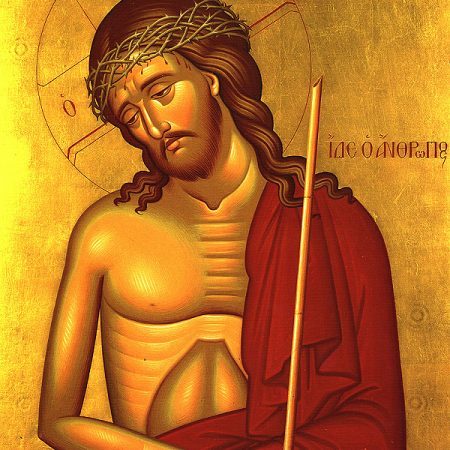

It is an irony that is at the centre of the reading we heard from Luke’s gospel, where Jesus is crucified with sign over his head declaring him to be the king, and it is something we would do well to get our heads around if we want to know what we are doing when we pray prayers like “Your kingdom come,” and “for the kingdom, the power and the glory are yours, now and forever, Amen.”

Let’s begin by dispelling one popular myth about the nature of Christ’s reign. The kingship of Christ is not some purely spiritual thing with no political implications. When we pray “Your kingdom come on earth as in heaven,” we are clearly expressing a dissatisfaction with the way things are on earth and an opinion about the way they should be. Such opinions are always political. We are praying that the political systems and regimes which protect the status quo will have their reign terminated, and that God will rule in their place. You can’t get much more political than that.

The fact that the Roman’s were involved in executing Jesus was for precisely this reason. The Romans recognised that any movement in which members vowed an allegiance to a power higher than Rome and set about living out of a value system that was at odds with the system on which Roman power was based was a threat to their grip on the empire. Such movements had to be either stomped out or neutralised through treaties which ensured that the movement’s aims would not conflict with those of the Empire.

When the Romans stomped out a perceived threat like Jesus, they were making a point. Capital punishment was not just punishment, but deterrence. And so they strung Jesus up with a sign over his head saying “This is the King of the Jews.” The message was all too clear. If anyone else gets any ideas into their heads about being any kind of a king and leading the people to rise up against Rome, this is what you can expect. Here is a failed king. And any king who doesn’t take his orders from Rome will likewise be a failed king and likewise end up strung up like this one. In Rome’s mind, the sign was hung over Jesus’s head to ridicule and snuff out forever any notion that he might be a king.

They were telling us in no uncertain terms that ‘King’ is not the right word for Jesus. And it isn’t. Maybe we manage to cope with it partly because we’ve seldom had to use the word for anyone else for over seventy years, but it has come as quite a shock to many Christians to be suddenly using the word they are used to using only of Christ to speak of Charles!

But even now, we know it’s the wrong word. Jesus deliberately fled whenever the crowds wanted to proclaim him king. He does not employ the infrastructure of a monarchy; he does not maintain palaces and royal staff, he does not proclaim the boundaries of a kingdom and establish military forces to defend them, he does not rule with an iron fist. Donald Trump might do many of those things, as the “no kings” rallies have been alleging, but Jesus doesn’t. The word ‘king’, as it is understood in our political world, is clearly the wrong word for Jesus, and yet we in the Church continue to use it. Why?

Because by deliberately using this wrong word we create a powerful metaphor which reveals a more profound truth. Or perhaps two profound truths. Firstly, when we say that for us, Jesus is King, we are saying that for us, no one else is king. In saying that we belong to the Kingdom of Jesus, we are saying that we are not submissive citizens of any other kingdom. We are saying that Jesus and his agenda sets our agenda, and that we will not give unquestioning allegiance to any other authority.

We do not set out to be hostile or seditious towards the countries we live in, but neither are we willing to cooperate with them when they ask us to compromise the values of love and justice and hospitality to advance their own national interests and agendas. Our allegiance is to the King of Love whose kingdom is not defined by national boundaries.

And secondly, we are saying something about those who would call themselves king or president or prime minister, or even bishop, here among us. We are saying something about what a ruler should be like. We are saying that, even now that he gets to sit on the big chair at Buckingham Palace, Charles will not be a true King, worthy of the name, until he’s ready to take on the crown of thorns for his people.

This is why I continue to use words like ‘king’ and ‘father’ for God, even though I understand why people want to avoid masculine names. Using them is not supposed to indicate that God is like the kings or fathers we are familiar with. It is supposed to say that kings and fathers in this world should be modelling themselves on what we know of God in Jesus, and that critique and challenge is constantly needed.

As the church, we must not stop criticising our kings, presidents, bishops and pastors until they fulfil the measures of kingship called for by the prophet Jeremiah, to be as caring and protective as a shepherd among the people, to deal wisely and to execute justice and righteousness in the land. I don’t think I’ve heard even their most ardent supporters compare Donald Trump, Anthony Albanese or Jacinta Allen to shepherds.

The true King is one who enters into all the suffering of his people. Emmanuel, God with us. He does not sit in a palace and issue decrees, he journeys with the people. If there is a wilderness to be passed through, he leads the way. If there is an execution to be faced, he is hanging there among the executed.

And according to what we heard from the gospel of Luke, it was hanging on a cross among criminals with thorns stuck on his head, journeying all the way in solidarity with the guilty and condemned, that another dying man recognised Jesus for who he was and begged acceptance into his kingdom.

And as Jeremiah makes plain, the true king is the one who brings about justice. The psalms and the prophets repeatedly call for earthly kings to emulate God’s example and be justice makers. Even before Israel chose their first king, God warned them through the prophet Samuel that a king would lord it over them, tax them harshly, and promote inequality and injustice. And that’s exactly what most of their kings did, and what most kings, emperors, presidents and premiers have done to this day.

But when we say Christ is King, we offer our allegiance to the one who will not rest until every cup is overflowing, until the pathway to fullness of life is open to every man, woman and child of every race, class and culture.

And so we gather at the Lord’s Table as subjects of no king but Jesus, whose reign is established in laying down his own life for the world. We gather as citizens of a kingdom that recognises no boundaries of race or nationality or gender or wealth or social class.

We gather, not as a people who think that because we were born in closer proximity to the world’s riches we have a greater ‘right’ to consume them than those born on the other side of a line drawn on a map, but as a people who know that all resources, even our basic daily bread, are the gifts of a generous God, given for the benefit of all humanity.

We gather as those who will laugh in the face of the petty claims of the world’s power mongers, even those who blasphemously try to invoke the name of Christ to legitimate their power-mongering. And even when they set a new feast in our calendar to try to substantiate their blasphemous claims, we will laugh all the louder as we celebrate the delicious irony of a feast which only further exposes their lies and confirms our faith in the One whose kingdom and power and glory are revealed in the unquenchable force of suffering love, now and forever. Amen.