A sermon on Daniel 7:1-18; Psalm 149 & Luke 6:20-31 by Nathan Nettleton

A video recording of the whole liturgy, including this sermon, is available here.

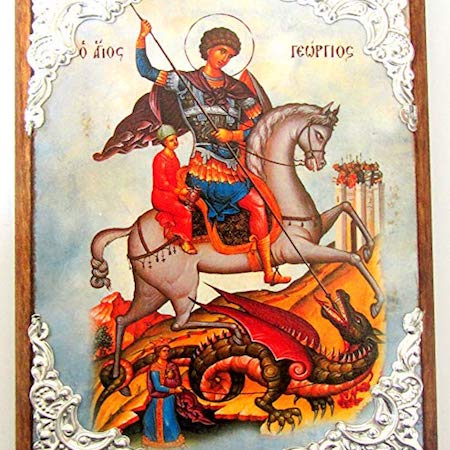

Have you ever noticed how often the saints of the past are depicted bearing swords? In many older church buildings, the stained glass windows and icons will contain more than a few swords, along with the names of some more recent saints of the church who bore arms for country, king and empire. And in tonight’s psalm we heard a call to arms: “Shout praise from your throat, sword flashing in hand to discipline nations and punish the wicked, to shackle their kings and chain their leaders, and execute God’s sentence.” Christians and Jews have a very long history of expressing their dedication to God in a willingness to stand up and fight against those thought to be God’s enemies.

In our first reading tonight, the prophet Daniel saw an apocalyptic vision of a cosmic conflict between empires, a conflict in which the saints of the Most High will eventually come out on top and possess the kingdom forever. But by what means do the saints prevail?

The Biblical scholars mostly agree that this account of Daniel’s vision was either written or re-edited during a particularly violent period of Jewish history less than two hundred years before the time of Jesus. Under the leadership of the Maccabees, the Jewish people rebelled against a series of foreign kings and emperors who had occupied the land of Israel and were seeking to forcibly assimilate the Jews into the imperial cultures. For the Maccabees, the only measures of one’s faithfulness to God were a refusal to compromise on Jewish law and a willingness to take up the sword against God’s enemies. They’d have loved tonight’s psalm.

So it is against that backdrop that Daniel’s vision was being heard. We didn’t hear all of it tonight, but in a nutshell, Daniel sees four great beasts coming up out of the sea, arrogant and violent beasts which he is later told represent four great kings or empires. Then he sees into the throne room of heaven where the Ancient One passes judgement on the beasts, stripping them of their dominion, and handing it instead to one like a new human who arrives on the clouds and whose dominion is everlasting.

Troubled and terrified by the vision, Daniel asks one of the heavenly attendants what it means. The explanation is short and sweet. The beasts represent four empires that arise, but it is the saints of the Most High who will receive the kingdom and possess it forever and ever.

Now while this vision would have been understood in relation to particular kings and empires back then, it is still in our Bibles and being read in our churches because it has a more timeless relevance too. The number of beasts, four, is like the mention of the four winds just before it. It represents the empires that come at us from the four corners of the earth, or in other words, all of them, all of the forces that seek dominion over our world and our lives.

For us in today’s world, the empires could similarly be seen as paralleled in the world’s great superpowers, but perhaps too the empires take new forms. Perhaps we should also think of them as global systems that conspire to claim our allegiance and to dictate how life is to be lived, more often than not demanding a myriad of compromises along the way.

Perhaps the global market economy is one of the beasts that arises on the earth. How often do we hear that the market is dictating this or that? It presses us all into the role of voracious consumers to fuel its need for perpetual growth, even though we know that perpetual growth is inevitably fatal. The only thing in nature that seeks to grow endlessly regardless of the cost is cancer.

Perhaps nationalism is one of the beasts that arises on the earth. It certainly commands our allegiance. How many of us would not flinch at being labelled un-Australian, or as acting against the interests of our country? How many of us have not chosen the Australian made product because of an instinctive assumption that Australian jobs matter more than jobs for people in Bangladesh? But we mostly don’t recognise what a vicious beast it is until it sprouts horns like the flag-waving neo-nazis and their march for Australia rallies.

Perhaps the industrial establishment is one of the beasts that arises on the earth. How else can we explain the seeming impossibility of achieving any realistic action to halt climate change, no matter how many of us pour into the streets waving placards? Who makes the rules, the people or the beast?

Perhaps even the Church has been one of the beasts that arises on the earth. How else can we explain how we colluded with European colonialism and baptised its worst excesses as it slaughtered its way across the world? How else can we explain a clerical caste system that fostered and covered up the abuse of tens of thousands of children and vulnerable adults?

I could go on, but you get what I’m saying, don’t you? Empire arises in a myriad of guises and seeks to corral us all into collusion with its interests. And as the last example showed, more often than not those who regard themselves as the people of God are wittingly or unwittingly drawn into compromise after compromise until we can no longer recognise that the current status quo is not actually ordained by God but by a beast seeking to usurp the dominion of God.

Faced with this daunting reality, it is entirely understandable that the saints who recognise the beasts for what they are would instinctively imagine that the only way to remain faithful is to take up the sword and fight back, inflicting whatever wounds we can on these beastly enemies of God. That was certainly how the Maccabees interpreted Daniel’s vision. In this clash of empires, God’s holy ones must resist and rebel and strike back with violence and be ready to face martyrdom if need be rather than surrender to the ways of the beasts.

But you know what? If today’s news media was writing about Judas Maccabaeus, we would think we were reading of one of the leaders of Hamas or ISIS, or perhaps one of the violent extremist Israeli settlers leading attacks on West Bank Palestinians. Like them, Maccabaeus was a firebrand advocate of extreme violence against the identified enemies of God. But we can see that just as his death elevated him to an even higher status among the hardcore supporters, a veritable saint, the same thing happens among religious terrorist leaders today whose deaths are immediately interpreted by their followers as martyrdom.

So if we recognise that our own biblical texts and much of the history of their interpretation have had far more in common with religiously motivated terrorism than we’d like to think, and we can see the evidence of it in the swords wielded by saints in Christian art, what are we to do with that?

Well, in Daniel’s vision, the beasts were stripped of their power when dominion was handed to the one like a new human whose dominion is an everlasting dominion and whose kingship shall never be destroyed. And we are the baptised followers of one who embodied that vision of the one like a new human. So we can turn to his words that we heard in our gospel reading tonight, and see what shape his dominion takes and what weapons he would have us wield in our conflict with the beastly empires that arise on the earth and seek to usurp God’s rule over us.

“I say to you that listen, Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you. If anyone strikes you on the cheek, offer the other one also.”

Suddenly, Jesus has turned the conventional interpretations of the apocalyptic visions on their head. Instead of meeting the violent hostility of the beasts with an equal and opposite violent hostility, the saints of God are called to meet it with the vulnerable but overwhelming power of love. We are no less involved in a violent struggle of empires, but now in the footsteps of Jesus, our only engagement with the violence is in suffering it, never in perpetrating it or reciprocating it. For what Jesus tells us is that if we reciprocate the violence and the hostility, we simply become a mirror image of the beasts, and thus become just the next beast arising on the earth.

(In 2019, Donald Trump’s speech announcing the killing of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was marked by gloating over the death and glorying in the gruesome details and the humiliation that seemed very similar to the very things we had most loathed in al-Baghdadi and his hyper-violent followers.)

Jesus is not dismissing or condemning the saints of the past who have expressed their devotion to God the only way they understood: in waging war against God’s enemies. But Jesus is calling us to break with that past, and model ourselves on the God who he reveals to be a God who rains down love on the enemies just as much as on the saints.

Perhaps too that call can be lived in learning from and modelling ourselves on some of those saints who stand out as examples of living in imitation of this non-violent God. Some of them have been relatively recent. Dietrich Bonhoeffer is a fascinating example because he struggled so openly with the question of whether stepping into violence is ever right. Oscar Romero was assassinated for his relentless non-violent advocacy for a compassionate state and society that would care for the poor and vulnerable. Desmond Tutu championed a pathway of healing and reconciliation for South Africa that insisted on truth-telling but avoided vengeful retribution.

“Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you.”

And you know what? What Jesus has so startlingly shown us in his own pattern of standing up against the might of the empire, the might of the beast, is that it is actually in this radical practice of meeting the love of power with the power of love that the beastly empires are shaken. For empires are held together by a unifying culture, and if we reciprocate their beastly culture of violent force, we actually contribute to the strengthening of that culture.

So Jesus calls us to embrace a new and radically different culture, a culture in which swords are beaten into plowshares and enemies, even the enemies of God, are seen as the recipients of relentless love and mercy until their empires crumble and love and mercy are all in all. This radical culture of love and mercy is the kingdom of God. If the saints of God will rise up and live out this culture in resolute imitation of Jesus their king, then indeed the great beasts that arise will fall, and the saints of the Most High will receive the kingdom and possess the kingdom forever and forever. Amen.