A sermon on Luke 13:1-9 by Nathan Nettleton

The cycle of Bible readings that we follow was first set in place during the 1970’s, and revised a bit in the 1980’s and 90’s, and so it feels rather unnerving when the set readings feel like they were specifically chosen to fit the news of the week. This is one of those weeks. Just when our news broadcasts and conversations with one another have been dominated by the massacre of worshippers during prayers at two mosques in Christchurch, our gospel reading opened by saying, “Some people came to Jesus bringing news of a massacre that had occurred in a place of worship. They said that a death squad, sent by Pilate, had butchered a group of Galileans while they were offering sacrifices.”

So immediately we are in this story. It’s our story too. Here we are ourselves, coming to Jesus with the news of our world, a massacre of faithful people at prayer, and just like those people who came to Jesus in our gospel reading, we want to know what Jesus will have to say about it. How will he interpret these events? What sense will he make of them? How will he speak into them? What will he ask us to see, understand and do?

This task isn’t going to be as simple as it might seem. Just because we are facing similar events, it doesn’t necessarily follow that Jesus would speak to us in exactly the same way about them. We live in a different culture in different times, and therefore our instinctive reactions to the events are different. And what Jesus responds to is not so much the tragic events themselves, but the responses and interpretations that people bring to those events. So if we are bringing different responses, and different questions, then Jesus might answer us in different ways. His replies to them are certainly our starting point, but we’ll still have work to do.

The first issue that Jesus raises might, indeed, startle us, because it is probably not where our minds immediately go. He raises the question of sin, and by implication, punishment. “Do you think that because these Galileans suffered in this way they were worse sinners than all other Galileans?” In other words, do you think this is some sort of divine punishment?

In our scientific age, not so many people assume that everything that happens is ordained by God, but in Jesus’s day, most people thought that way. In the old Hebrew prophets, we again and again come across this exact interpretation. The Babylonian army came riding over the hill and destroyed our city, which must mean that God was using them to punish us for our failure to live up to God’s requirements and expectations. We still sometimes refer to natural disasters as acts of God, but violent massacres and military disasters were frequently interpreted that way too. If God was happy with us, God would protect us, so if we have fallen victim to violence or disaster, God must be angry with us.

“Do you think that because these Galileans suffered in this way they were worse sinners than all other Galileans?” It might not be so common now, but it’s certainly not unheard of either. You will frequently hear individuals ask “Why is this happening to me?” with the implication being that life is expected to be fair and therefore I must have done something bad to deserve this.

After the Black Saturday bushfires ten years ago, a prominent preacher who does not deserve to be named asserted that the horrific deaths were God’s punishment for Australia’s increasing tolerance of homosexuality and abortion. And this past week, we heard an obnoxious racist in our national Senate argue that the Muslim community had brought last week’s massacre on themselves. He even misquoted Jesus to back up his bigoted views. These views are out there, even today.

But Jesus gives them no oxygen at all. “Do you think that because these Galileans suffered in this way they were worse sinners than all other Galileans? I tell you no! Not at all.” Jesus flatly rejects any connection. Tragedies and disasters do not happen to anyone because they are more deserving of them than others. These things are not punishment for sin. Shit happens. That’s all. It’s random. It’s not fair. It just happens.

But then Jesus says something that does our heads in. It sounds like he’s contradicting what he’s just said. “Do you think that because these Galileans suffered in this way they were worse sinners than all other Galileans? No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all perish as they did.” What?!! You’re telling us that they didn’t get targeted because they were sinners, but that if we don’t repent, we will be targeted. What’s that about? How are we to make any sense of that?

Here’s the thing. Nowadays we tend to think of the word “repent” as a specialist religious term entirely related to sin. So we hear it as meaning “stop sinning”. But it doesn’t mean that. It can, but it means a lot more than that too. At its most basic, the word means “change your mindset”, and while a change of mindset might result in leaving some sin behind, that is not always the focus. If I was trying to change your mind about something, you wouldn’t necessarily assume that I was accusing you of sin.

There are at least two other ways that we could understand the word “repent” in what Jesus says here that would make much more sense of what he is saying. He probably has both of them in mind.

The first is that he is trying to change people’s minds about the connection between sin and disaster or suffering. Actually, there is no question that he is trying to do that, because that is precisely what he says in the part we have already looked at. “Do you think that because these Galileans suffered in this way they were worse sinners than all other Galileans? I tell you no! Not at all.” But why would failing to change their minds about that expose them to suffering the same fate?

Well, to some extent, we are destined to live in the world we believe in, because our beliefs create so much of the conditions of our lives. So if you were to believe, contrary to what Jesus says, that last week’s massacre in Christchurch was some sort of punishment sent from God, and that those who displease God are constantly at risk of disasters at any moment because God’s anger will catch up with them sooner or later; if you were to believe that, you would probably find yourself living in a high state of anxiety and fear and rigidity, because you could never be sure if you were making the grade. And you would find yourself trapped in a system of suspicion and condemnation and judgement, because you would be shaping the world around you in the image of the angry judgmental God you believed in.

Some years ago, I sat down with a prominent conservative moral crusader who was angry that I was advocating the acceptance of LGBT+ people in the church. I discovered that one of the things we had in common was that we had both been divorced and remarried, but I also discovered that he felt desperately insecure about whether God would forgive him for that and accept him. And it seemed to me that he was horribly trapped in a judgmental world of his own making, and that his fierce moral crusading was an attempt to make it up to his angry intolerant god.

“No, I tell you; but unless you change your mindset, you will all suffer the same fate.”

There is a second thing that I think Jesus probably had in mind, and this one may be even more relevant to our world in the aftermath of horrors like the Christchurch mosque massacres. One of the themes that runs through much of the teaching of Jesus, but is easily missed by us, is his concern about the Jewish people’s increasingly reckless resistance to the colonialist occupation of their country by the Roman empire. There had been numerous violent uprisings by wannabe Jewish messiahs, and they had all been brutally crushed by the Romans.

When Jesus says things like “Those who live by the sword die by the sword”, he’s actually warning his compatriots that if they think they can solve their problems by taking up arms, they too will be brutally crushed. We heard Jesus’s cry over Jerusalem last week: “Jerusalem, Jerusalem. I tried to warn you. I tried to gather you like a hen gathers her chicks, but you wouldn’t follow my lead. And now you are doomed.” And not too many years later, sure enough, the Romans got sick of Jewish unrest and marched in and destroyed Jerusalem.

“No, I tell you; but unless you change your mindset, you will all perish as they did.”

Can you see how perfectly that fits the context? It was Roman soldiers who carried out the massacre that was reported to Jesus. And the second disaster he comments on was a collapsing tower. How many people died under collapsing buildings when the Romans destroyed the city? “Unless you change your mindset and stop thinking that violent retaliation is the answer, you will all perish as they did.”

In the past week, the world has been wowed by the exceptional leadership shown by the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Jacinda Adern. Our expectations of our political leaders have become terribly low in recent years, and her strong, compassionate and unifying example has been a wonderful breath of hope. The political responses on this side of the ditch have been a lot less edifying. The feral senator was certainly the worst, but there was no need for our Prime Minister to take the bait when the President of Turkey started beating his chest. Too much strongman posturing and compulsive tribalism. “Unless you change your mindset and stop thinking that divisive nationalism is the answer, you’ll all perish as they did.”

So Jesus is telling us not to try to interpret these events as punishments from God, but to examine them carefully to see what we can learn about what is threatening our society from within. This massacre is one of the ugly fruits of the divisive tribalism that stalks your streets and even the halls of parliament, so take a good look at yourselves and change your mindset, change your ways. “Unless you change your mindset and stop thinking that anger and hating and divisive nationalism and arming yourselves is the answer, you will set your world ablaze and you’ll all perish as they did.”

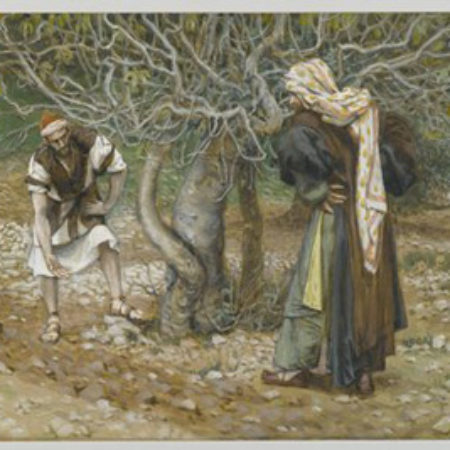

Then, to conclude, Jesus told this parable: “These people had a fig tree growing in their vineyard; and one day they decided that it wasn’t good enough for them. ‘See this,’ they said. ‘This fig tree has refused to assimilate to the culture of our vineyard. The vines produce lovely fruit, but this fig tree just consumes our resources and produces nothing of value. We want it ripped out, roots and all, and got out of here. And we want stronger fences and quarantine laws so that none of its kind gets in here again. Cut it down! Rip it out! It doesn’t belong. Why should it be wasting the soil?’ But their expert gardener spoke up in defence of the tree, saying, ‘No. It has made its home here and it should be safe here. Leave it be, and I will tend to the soil around it and feed and water it and make it feel at home. Just watch and see all the good fruit that will come of it. It will be worth it. Trust me. And if you are so blinded by your vine-supremacist views and your prejudice against the fig tree that you come armed to cut it down, you’ll have to cut me down first.’”

My friends, we are gathered here tonight at the invitation of that gardener, of Jesus the Christ, who stood up for us in front of the angry mob and was himself cut down first trying to protect us. We are gathered in response to his invitation to change our mindset, to give up imagining that our world can be improved if someone else, some other, is violently uprooted and rejected from our midst. And we are gathered in response to his invitation to change our mindset and stop imaging God as a bloodthirsty judge who endorses our violence and approves of our divisive moral supremacies. We are gathered to receive his gracious gift of himself, broken and poured out and offered to us freely, that we might know ourselves beloved, liberated, healed, united, and destined for life and love in all its fullness.

0 Comments