A sermon on Colossians 1:11-20 & Luke 23:33-43 by Nathan Nettleton

In the church calendar, today is designated as “Christ the King Sunday”, and back in the mid 90’s, I preached a sermon for this Sunday titled “Can Christ be King if we become a republic?” I still like the title, and it was a bit tempting to preach it again tonight after the disastrous week the British royal family have been having. The arrogance and entitlement that monarchy so easily breeds have been horrifyingly displayed, albeit by one who was only eighth in line for the throne.

But I have resisted the temptation of the easy target and wish to jump in another direction tonight. My starting point is related though, because I want to start with the fact that monarchy or kingship has become a rather unfashionable idea. Many churches, especially those who are of a less triumphalist persuasion, have shied away from talking of Christ as King, because it doesn’t seem very politically correct.

The sort of critique of kings that we heard in our first reading from the prophet Jeremiah has continued to grow over the centuries, and while there are still a few people who defend the continuance of existing monarchies, there are very few people who would argue for the creation of new ones where they didn’t already exist. And so, if we are wary and distrustful of kings, we are likely to feel rather uncomfortable about using such an image to describe Jesus.

Some churches have therefore changed the name of this day to “Reign of Christ” Sunday, but for myself, I can’t see how that makes much difference. Apart from being gender neutral, I can’t see that it really makes much difference to the kind of political imagery that it evokes.

I’m not going to propose a new name for the day, but I do, however, think that there is another more helpful image that we might usefully consider in thinking about what it is that we are trying to say about Jesus and his impact on us and our world. But in order to get to it, I want to first look at how the king language is used in a couple of the readings we heard tonight.

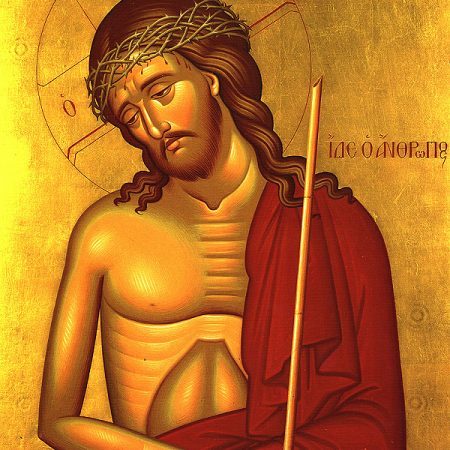

In our gospel reading, we heard Jesus being described as a king in a sarcastic and mocking way as he was being executed. One of the grounds on which Jesus’s opponents had managed to get him sentenced to death was the allegation that he had claimed to be a king, and so now as he is hung up to die, the soldiers were cruelly taunting him with the label, saying, “If you are the King of the Jews, see if you can get yourself out of this one. Save yourself!” And to further the insult, they hung a sarcastic sign over his head saying, “This is the King of the Jews.”

So, added to the fact that Jesus repeatedly refused the title of king throughout his ministry, you could conclude at this point that the gospel writer wants us to hear this title in an entirely negative fashion and reject it entirely.

But then suddenly, it comes back in quite a different light. One of the criminals being executed alongside him says, “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.” Into his what? His kingdom. “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.” And although you could maybe make an argument out of the fact that Jesus doesn’t say, “today you will be with me in my kingdom” but “today you will be with me in paradise”, it really doesn’t look as though Jesus is rejecting the idea or trying to correct the man.

What it looks like is that the gospel writer is indeed engaging with the idea of Jesus as king and putting the sarcastic usage alongside this honouring usage as way of challenging us to be careful about how we use this title and to make sure that we do not use it to put mainstream political ideas about kingship onto Jesus but instead rethink it in light of what is happening right here at the cross. More of that shortly.

Moving across to our reading from Paul’s letter to the Colossians, the title “king” is not used, but there is an unmistakeable reference to Jesus having a kingdom. “God has rescued us from the power of darkness and transferred us into the kingdom of his beloved Son, in whom we have redemption, the forgiveness of sins.” We have been transferred into the kingdom of God’s beloved Son, Jesus.

So in both readings, in as far as the idea of Jesus being a king or having a kingdom is used positively, it is set up in contrast to something else. There is this kind of kingdom, and that. There is the power of darkness, and there is the kingdom of God’s beloved Son. There is the kingdom that crucifies innocent people, and there is the kingdom that forgives and welcomes guilty people.

And although we don’t tend to use the idea of kingdoms to think about such things nowadays, because we don’t have much in the way of kingdoms at all anymore and those that we do still have are mostly not terribly admirable political entities, we do have another word or another idea which we use all the time and that seems to capture the essence of what is being spoken about when the Bible talks of the kingdom of God’s beloved Son. And that word is “culture”.

Think about it for a moment, and I think you will see that much of the way we use the word “culture” is the same as the way previous eras would have used the word “kingdom”. It even has the same sorts of political overtones when we speak of things like “cultural imperialism” or “cultural domination” or “cultural assimilation” or “protecting our culture”.

And if we speak of the “culture of God”, it protects us from the too-easy error of hearing in the phrase “kingdom of God”, a geographical reference. For like the “kingdom of God”, a culture is not bound to any location, but can spring up anywhere among those who adopt it, and form colonies of difference among any other dominant culture.

The culture of God’s beloved Son is an ethos, a set of attitudes and behaviours, a way of life, and its nature is made clear in this story we heard of the execution of that beloved Son, and is summarised in the line from the reading to the Colossians when the Apostle said that we have been “transferred into the kingdom of his beloved Son, in whom we have redemption, the forgiveness of sins.”

Redemption and the forgiveness of sins. These are very closely related ideas, because both imply the cancelation of a debt. And to see what this looks like, we need look no further than to the story of Jesus at the cross, putting it into practice under the most extreme circumstances. Even as the iron spikes are driven through his flesh, and even as the sarcastic taunts ring in his ears, Jesus lays down all claim for retaliation or vindication or vengeance, and prays a prayer of the utmost compassion for his torturers and abusers: “Father, forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing.”

That is the most extraordinary forgiveness, and there is the birth of a most extraordinary culture, right there in that prayer. A culture of extreme radical forgiveness. A culture of almost incomprehensible grace.

And we find ourselves on both ends of that foundational act of forgiveness, for we, with our frequent willingness to turn a blind eye to the scapegoating and sacrificing of those our privileged world wants to rid itself of, are undoubtedly among the complicit crowd for whom Jesus prayed forgiveness. And now as those who have been redeemed in that incomprehensible forgiveness, and who would thus follow Jesus in freedom and gratitude, we are among those who are called to live out the new culture founded in that act, and to follow him in similarly renouncing the cultures of judgements and punishments, rights and wrongs, worthies and unworthies, privileged insiders and illegal aliens.

Right there on the cross comes the further illustration of what this looks like when that prayer of forgiveness, that culture of forgiveness, is personalised and responded to. The criminal hanging alongside Jesus hangs there dying, agonisingly aware of his own guilt and of the consequent fact that, as one who lives in a culture that is founded on a justice that always ensures that the guilty are made to pay the full penalty for their crimes, he is reaping what he has sown and copping precisely what he deserves.

Yet, the moment he looks to Jesus for even the faintest glimpse of mercy, he is embraced in a welcome beyond anything he could possibly have dreamed of. “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in Paradise.” Clearly the culture founded in Jesus here at the cross is not a culture that is trying to turn around the boats and close its borders to all but the worthy, the insiders, the deserving and productive.

So there we have it, the culture of God’s beloved Son, into which we have been transferred, redeemed from the power of darkness, our sins forgiven. There we have a kingdom or a culture that we are called to surrender to, to embrace, to begin to live out as subversive communities whose radical culture is always going to be deemed a threat to the dominant culture around us.

Without our embrace of this culture, this ethos, the church would be nothing but another social grouping perpetuating the normal patterns of the eye-for-an-eye, us and our families first, world around us. But when this culture truly takes root among us and takes hold of us and transforms us, a new world is born in the midst of the old, and the welcome is open to all, for the culture of God’s beloved Son is a culture of freedom and forgiveness and hospitality and the most outrageous, scandalous, all-embracing love.

0 Comments