A sermon on Galatians 1:11-24; 1 Kings 17:8-24; & Luke 7:11-17 by Nathan Nettleton

The theological college where I studied and still do some teaching, Whitley College, has throughout its history been criticised by some people in the churches. Actually, nearly every theological college, no matter where they might be on the theological spectrum, cops similar criticisms. There is always some tension between the colleges and churches, and if there wasn’t they’d probably serve no purpose. But one of the criticisms sometimes levelled is that people go there and lose their faith.

Now it is perfectly obvious that many graduates of the college still have plenty of faith, but the criticism is frequent enough that there must be something in it. There seems to be at least two situations that produce this criticism. The more frequent one is that people spend a few years studying, and by the time they are finished, their belief systems are so changed that some in their home church interpret the change as a falling into error, a falling away from the true faith, which of course is the faith they unquestioningly hold. This happens quite often, and unfortunately some new graduates can be quite zealous and arrogant and condescending towards those who still believe the way they once believed, and that inevitably increases the tension.

In reality, those students frequently had quite a crisis of faith at some point in their studies. All of us, especially when we are young, can be overly confident that we have it all worked out, and when we see new light and truth breaking forth from God’s word, something almost inevitably has to fall over to make room for the new discovery. If God is like this, then God can’t be like that after all. Those who come through this crisis find much of their old belief structures dismantled, and they emerge with new belief systems built over the rubble of the old. And if the space hadn’t been cleared, there would have been no room for building anything new.

But there are a second group of students who don’t survive the crisis. Sometimes they are so disillusioned or terrified by the collapse of their old faith systems that they drop out and flee. But having fled, they can no longer believe the things they used to believe, and they didn’t stay long enough to allow the college to help them rebuild something more solid in its place. So they really do lose their faith. In my experience, this second group is far less numerous, but they do exist.

I didn’t quite have either experience. I arrived at Whitley in the aftermath of the failure of my first marriage. That experience had already kicked down the dodgy belief structures of my zealous youth. I was already sitting amidst the rubble and ruins, and I was hungry to know whether anything meaningful could be rebuilt. So in a way, I had a head start on many of my peers.

Like me, many of you didn’t need to go to theological college for life to knock down your faith systems, and fortunately, many of you have been able to find new life and faith without having to invest in tertiary studies to do it. Many of you found your way into this church partly because at some point, your faith in a previously held belief system crumbled or came crashing down around your ears. Some of you arrived here quite wounded, and not fully convinced that it was even safe to give the church and its faith another chance. Some of you have wounds that are still quite raw. Many of you remember the real fears of looking back on the recent collapse of everything you had thought you believed and trusted and having no idea what might come next.

Collapsing faith systems were a bit of a theme in all of tonight’s readings, although the only one where it was really explicit was our reading from Paul’s letter to the Galatians. But there are interesting links between all three readings, and those links will help us see this theme in all three.

In Galatians, Paul doesn’t allude directly to the story of Elijah that we heard tonight, but he does allude to the Elijah stories more generally. Paul’s portrayal of his former self as a violent zealot intent on purging Israel of any threats to the purity of its faith would have held up Elijah as its number one role model. And when Paul speaks of encountering the risen crucified Christ and the consequent collapse of his zealously certain faith system, he alludes to Elijah’s faith crisis and disappearance into the wilderness to wrestle with a God who appears to him not in signs of power, but in a still small voice, or a crucified victim.

Paul looks back on the demolition of his rigid belief structure as the beginning of his salvation. Only when it all came tumbling down, and he was left wandering uncertainly in the wilderness, could the full meaning of the revelation of a God who embraces weakness and failure begin to lay firm foundations in his heart and mind and allow faith to rise anew.

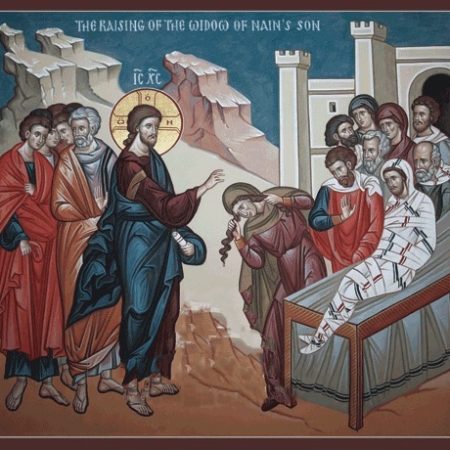

The connections between tonight’s story of Elijah and the widow in Zarephath and our gospel story of Jesus raising the dead son of the widow in Nain are a lot more obvious. Luke the gospel writer is clearly reminding us of the way Elijah raised the widow’s son when he tells us of Jesus doing the same.

He is also pointing forward, and he wants us to remember these stories later when Jesus himself is being carried off for burial, followed by his grieving mother. Could this burial procession too meet a still small voice that can raise new life when we are sitting surrounded by the rubble of death, with all our hopes and all our confidence in ruins around us? When the gospel writers make these kind of connections, they are reminding us not to think of these stories just as random, one-off miracle stories, but to look for the patterns that point to who God is and what God keeps doing, over and over.

Sometimes it is only when our old certainties collapse that we can begin to see these patterns and realise that the truth about God was there for us to see all the time, but we were blinded by what we thought we knew.

I want to make a bit of a detour though in order to tie all these stories together, because interestingly, tonight’s gospel reading is not the only time that Luke makes links between the story of Jesus and the story of Elijah and the widow in Zarephath. Do you remember the story of Jesus preaching for the first time in his home town of Nazareth, and although it starts well, by the time he is finished, the hometown crowd are ready to lynch him on the spot? The turning point that enraged them was when Jesus makes a particular use of two stories of the prophets Elijah and Elisha.

“Truly I tell you, there were many widows in Israel in the time of Elijah, when there was a severe famine; yet Elijah was sent to none of them except to a widow at Zarephath in Sidon. There were also many lepers in Israel in the time of the prophet Elisha, and none of them was cleansed except Naaman the Syrian.” (Luke 4:25-27)

That might sound innocuous to our ears, but the reason this drove the people into a murderous rage is that Jesus was taking a sledgehammer to the foundations of their faith system. If they hadn’t clapped their hands over their ears and begun shouting, the whole house of cards might have collapsed around them.

Why? Well this brings us back to the zealous fury of Saul and Elijah and so many of us, once upon a time. It is also closely related to what I was saying last Sunday about rigid boundaries. More often than not, the fragile but fiercely held faith systems that eventually come under threat are founded on beliefs about who God loves and blesses, and who God rejects and condemns. God is with us, and God is against them.

In the ancient world, this was often understood geographically. Elijah was involved in a conflict between the God of Israel, and the apparent threat from foreign gods. Over time, and especially through the experience of exile in foreign Babylon, the Israelites came to believe that their God was not limited to the geographical boundaries of their homeland, but for most, this only strengthened their faith in God’s exclusive care for them. God loves and cares for us faithful Israelites, but God hates and condemns those terrible pagans with their horrible pagan gods.

So when Jesus quotes stories of their own zealous Israelite heroes, but uses those stories to suggest that God might love and care for gentile pagans like the widow at Zarephath and Naaman the Syrian every bit as much as the Israelites themselves, he is attacking the fundamentals. If we can’t believe that God has chosen us and favours us, what can we believe?

This, of course, is not just about needing to be the favourites. The Israelites have received the holy law of Moses and their whole lives are shaped by it. The gentile pagans live in ways that are obviously repugnant to the law of God. Of course God would favour the holy and law-abiding Israelites over the lawless pagans with their disgusting godless ways.

And now perhaps you are beginning to hear how similar this is to the faith systems that so many of us have or inhabit today. It seemed self-evident that God would favour those of us who had committed ourselves to shaping our lives according to the will of God as revealed in the Bible. After all, if we go to all that trouble, surely God should single us out for special blessings and rewards.

That’s certainly what I thought. That’s why my marriage break-up was such a faith crisis. I was a zealous, bible-studying, praying, evangelising, holiness-seeking Christian. How could God fail to recognise that and protect me from this disaster? How could it be that there were Muslims and Hindus and even atheists and occultists who had better marriages than a faithful Christian like me. There even seemed to be homosexual couples whose relationships looked more blessed than mine, and I had always been sure that you couldn’t be much further from the favour of God than that. How dare God bring new life and healing to them and not to me. The God of my faith system had failed me. Perhaps God wasn’t who I thought he was. If I could have risen up with the people of Nazareth and thrown him off the cliff, I would have.

But sitting there in the rubble of my collapsed house-of-cards faith system, I too met a crucified messiah and a voice like a sound of sheer silence. And I know that many of you have had and are having that same experience. We are encountering God as the crucified victim of exactly the kind of religious zealots some of us used to be. We are, like Saul, hearing that still small voice saying “I am Jesus who you are persecuting.” We are discovering, painfully, that Jesus is just as much among those we thought were cursed by God as he is among us. “I am Jesus who you are persecuting.”

And we are discovering, to our astonishment or bewilderment or sometimes even offence, that just when we are wailing over the dead corpse of our failed beliefs as it is carried off for burial, there we are confronted by a stranger, a compassionate stranger, a stranger who is not afraid to reach out and touch the putrid corpse, and who breathes again the breath of life and turns our mourning into dancing as hope and faith are reborn, never to be the same again.

So here we are again tonight, gathered around the table of this same crucified Lord, gathered to be confronted again by his brokenness and scandalous lack of holiness as he welcomes and offers himself, broken and poured out, to all manner of people, the law-abiding and the lawless, married and divorced, heterosexual and an acronym soup of other sexualities, people of all faiths and people of no faith, recovering fundamentalists and tired old liberals who are finally catching fire again. Here we are, all manner of misfits and couldabeen respectables, with no need to pretend, because Jesus welcomes us just as we are, and says new life starts here. Don’t be afraid. Even the prophet Elijah and the Apostle Paul saw their faith collapse before they met Jesus here in the rubble. You’re in good company. When the dust of the crash clears, Jesus will be there to meet you. The bread will not fail, and the breath of life will blow life into you again, and all will be extravagant love.

4 Comments

Your sermon reaffirmed to me it’s okay to have a crisis of faith or even no crisis. What’s even more scarey to me is to deny your faith or to pretend you have faith. But the most gracious thing about seeking to follow Jesus is that he is waiting to receive us no matter what little faith we think we have.

Thanks Nathan. Your comments about old held faith and belief collapsing really resonated to my recent experiences of church. South Yarra Baps feels like a really nurturing, gentle place to heal & pick up the pieces again. I am enjoying the ‘realness’ of your sermons

Thanks, George. Many of us have been wounded by churches and their leaders. Some of the early church leaders used to call the Eucharist the “medicine of life”. There really can be healing in the church, although I guess it is also true that medicines administered badly can be toxic. I hope and pray that we can continue to be a place of healing for you.

I too have walked this path not via crisis of faith but by a small voice inside that questioned the path of those that are acceptable and those who are not, – when I could not invite in someone who needed a place “to be” in, because the “inside people” could not have accepted them. When I walked with Roman Catholics and found them totally gracious to me but others in my Church only saw doctrinal difficulties. One Saturday afternoon many years ago God said “You are acceptable to me as you are today not as you will be in 10 years time” So If God can do that for me then I must too walk this path – regardless of who crosses my path – and so slowly I an learning to walk the path of welcome and acceptance – thank you for giving words to this experience