A sermon by Alison Sampson on Luke 5:1-11

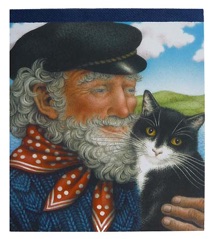

When I was a girl, I imagined Simon and his mates to be lovely Cornish fishermen. I thought of them as stocky men with hands like shovels, and twinkly blue eyes. They probably wore wellies and smocks. I loved the idea of being out on a boat at night, sailing under the stars, and of puttering back into a safe stone harbour at dawn. I imagined holds full of pilchards, and scrawny cats who kept an eye on everything.

When I was a girl, I imagined Simon and his mates to be lovely Cornish fishermen. I thought of them as stocky men with hands like shovels, and twinkly blue eyes. They probably wore wellies and smocks. I loved the idea of being out on a boat at night, sailing under the stars, and of puttering back into a safe stone harbour at dawn. I imagined holds full of pilchards, and scrawny cats who kept an eye on everything.

Now that I am older,  I am learning that Cornwall is not as idyllic as I thought. It has long been the poorest county in England. It was the last county to have a university; for centuries, any Cornishman or woman seeking tertiary education had to leave. Food produced in Cornwall is sent away to national distributors, and comes back branded, and expensive. Even fishing is not the smooth sailing I thought. It is an industry that is erratic and dangerous. There are good catches, and there are bad catches. Seas are rough, boats are lost, and in early times many people went hungry. In fact, the reason I stand before you now is because of famine. In the 1840’s, food was being produced in Cornwall – but it was being sent to the ruling classes in England. And the mining industry

I am learning that Cornwall is not as idyllic as I thought. It has long been the poorest county in England. It was the last county to have a university; for centuries, any Cornishman or woman seeking tertiary education had to leave. Food produced in Cornwall is sent away to national distributors, and comes back branded, and expensive. Even fishing is not the smooth sailing I thought. It is an industry that is erratic and dangerous. There are good catches, and there are bad catches. Seas are rough, boats are lost, and in early times many people went hungry. In fact, the reason I stand before you now is because of famine. In the 1840’s, food was being produced in Cornwall – but it was being sent to the ruling classes in England. And the mining industry  was collapsing. So there was no money, and no food to buy anyway. It led to a mass migration; some 20,000 Cornishmen left every week. My ancestors were among them. The landscape is beautiful, but for many in Cornwall, life has been, and continues to be, tough.

was collapsing. So there was no money, and no food to buy anyway. It led to a mass migration; some 20,000 Cornishmen left every week. My ancestors were among them. The landscape is beautiful, but for many in Cornwall, life has been, and continues to be, tough.

In the same way, now that I am older I am learning that my images of ancient Galilee were also romantic. And I am learning about fishing. I have learned that fishing was deeply embedded into every aspect of Galilean life. Many of the Jesus stories came out of fishing villages: the harbour town of Capernaum; Bethsaida, which was also known as the Temple of the Fishing God; Gennesaret and Gerasene, and others. One Mary came from Magdala; and the town of Magdala had a second name: Tarichaea, or “Processed Fishville” – the place where they make salty fish. A high proportion of Jesus’ first followers came from fishing villages, and were involved in one way or another in the fishing industry.

And this industry was hardly idyllic. It wasn’t the multimillionaire tuna fishermen from Port Lincoln. Nor was it just blokes in boats, catching a few fish and bringing them back to a local farmer’s market in a free enterprise economy. And it certainly wasn’t high status. Because they were involved in the production of food, Cicero included fishermen and fish sellers on his list of the most shameful occupations. And because they were away from their homes and their families at night, their low status was entrenched in most people’s eyes.

So fishermen were low status. They were engaged in dirty and dangerous work, in an industry where every aspect was controlled by the state. And this state wasn’t a socialist republic, using taxes to fund schools and hospitals. Instead, the state – the Roman Empire and its client states – existed as a means of controlling a large peasant population, and of funnelling as much wealth as possible to the ruling elites.

To gather the wealth, the state focussed on local industries, such as fishing. Around the Sea of Galilee, the state built harbours and sea walls and piers, and offices to administer fishing licenses and to collect harbour taxes. The important royal city of Tiberias was built to administer the fishing industry; yet the gospels barely mention it – and when they do, it is to suggest that it is only outside of that city that people experienced abundance.

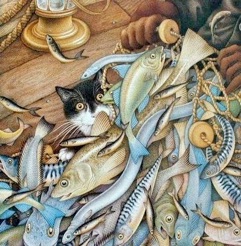

The state collected vast taxes, not through tedious paperwork and convenient electronic funds transfer, but by any means, up to and including extreme physical violence visited on female family members. You couldn’t be a fisherman without encountering multiple layers of state control and taxes. You had to be part of a collective, which contracted for the fishing lease. You were taxed on using the harbour; and you were taxed up to 40% of the catch. Even the distribution of the catch was controlled by government-approved wholesalers. By the time all the taxes were paid, only the rich could afford to eat fish. The physical dangers and the heavy burdens of fulfilling the fishing lease led one Egyptian commentator of the time to describe fishing as the most miserable of all professions.

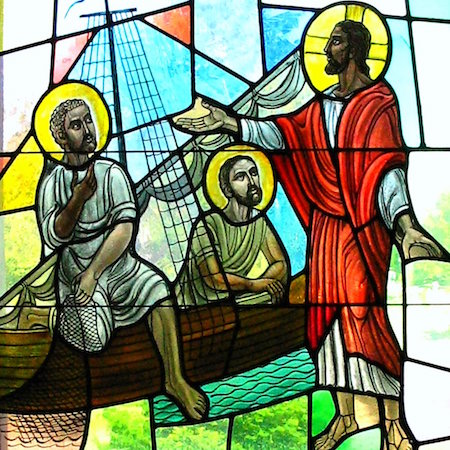

It is into this context that tonight’s story is set. It is to fishermen and their families that Jesus is preaching; it is fishermen who left their nets, and followed him.

When they left their nets, they left their means of meeting their legal obligations. They walked out of their collective, which now had to fulfil its fishing leases without them. They left their means of earning an income. They left wives, children and other family. They left everything, absolutely everything, to follow Jesus.

What sort of desperate hope would lead a man to do that? Again, I go back to what I know: the stories of Cornishmen coming to Australia. In the 1840’s, in some areas of Cornwall, between infant mortality, waterborne disease, mining accidents, lung disease, and the ravages of malnutrition, the life expectancy was just 19. By contrast, what with the fresh air, the food, the dryness and the mining techniques in Burra, South Australia, the life expectancy was 45. Brave the journey, and you more than doubled your life expectancy and that of your children. And that is why Australia is full of Sampsons and Bennetts and Penberthys and Curnows and Goldsworthys and Perrins and all the other old Cornish names.

Of course, these stout Methodists were not following the human person of Jesus in the first century. But they do give a glimpse of what might drive a man to leave his family and his work, and to head into a wildly uncertain future.

And I come back to hope: hope that there is more to life than working to the point of collapse. Hope that your work could lead to some form of richness, not just constant hunger and emptiness. Hope that you could live free from the violence and exploitation of Empire. Hope that life could be bigger, more abundant, more extravagant – even if for just a little while.

Today, this story of indentured fishermen dropping everything to follow Jesus speaks to women in sweatshops, men in diamond mines, and children in tomato fields. It speaks to young men in Afghanistan, and families in Syria, and the poor of America. It speaks to people who work their guts out, and yet still struggle to pay the rent and feed their kids properly, and who get no respect. Here, here is a man who offers freedom, and nets so teeming with life that they begin to break.

But this story is also for those of us higher up the economic scale: to open our eyes to the grief of the world, yes; but also to show us the way out of empire. Many of us betray deep fear, and full capitulation to the system. We see this in the hours many of us work, with little time for family or friends or lazing about in the presence of God. We see this in how few of us give generously, let alone sacrificially, out of our abundance. We see it in the resources we pour into insurances, and investments, and superannuation, with little concern for how the money is used, or how it could be used in a different economy. We see it in the way we consume without regard for effects, whether food or clothes or electronics or petrol. We are terrified of poverty; we are terrified of simplicity; and we are terrified of those on the underside of the system.

And so even to us, Jesus offers hope, and a path to freedom. A path which might lead us to question the hours we work, and to wonder about our priorities. A path which might challenge us to rethink the ways we are financially enmeshed, with our bank accounts, our home loans, our investment portfolios, our superannuation. A path which is shared with strangers from all different backgrounds, strangers who might initially seem threatening, but who one day become friends. A path marked by hospitality and generosity, where the abundance is no longer parcelled off into small households, but is shared, and everybody has more than enough.

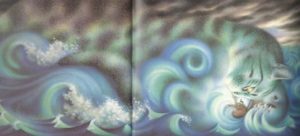

Such a path can seem terrifying when we try to control our own lives, when we place all our trust in work and money and investments for our future. Such a path seems too holy for a sinful people, who cannot see our way out of empire. “Go away from me!”, we cry, as we fall to our knees.

But Jesus puts out his hand in infinite tenderness, and raises you to your feet. “Do not be afraid,” he says, “this is who you are.” And he points you in a new direction, full of strangers and dangers and turmoil and wonder. And in that vision of a new way, a new future leaping with silvery hope, you will find the courage to leave everything. Amen. Ω

0 Comments