A sermon on 1 Corinthians 2:1-16 & Matthew 5:13-20 by Nathan Nettleton

A video recording of the whole liturgy, including this sermon, is available here.

Mark Twain once said that what bothered him most about the Christian message was not the things he couldn’t understand, but the things he could. I suspect that he was also suggesting that we often avoid the easily understandable but uncomfortably challenging parts by spending our time arguing about the things that are much more difficult to understand.

We heard part of Jesus’s sermon on the mount tonight, and surely one of the reasons that the sermon on the mount is so often neglected in Christian teaching is that most of it is perfectly clear but seriously challenging. “Love your enemies. Pray for those who persecute you. Turn the other cheek.” No one needs a philosophy or theology degree to understand such things, and having a degree won’t make them any easier to put into practice. Perhaps that’s why it is so tempting to brush them aside as unrealistic utopian dreams of a future age, and look for something more impressively complicated.

When the Apostle Paul addressed himself to the people of ancient Corinth, he was speaking to one of the most intellectually sophisticated cities of the Greco-Roman world. It was a bit like how today’s English speaking world thinks of Oxford and Cambridge or Princeton and Harvard. The epicentre of higher education, culture and philosophy.

But Paul decides to address them “knowing nothing among you except Jesus the messiah, and him crucified.” That is, he chose to address them with nothing more than something he knew most of them would dismiss as crude and primitive nonsense, because he is not willing to allow the gospel to be taken as just one more complex and intriguing philosophy for detached academic discussion among the intellectuals. It is too important for that.

You will remember that last week we heard him say, from a few verses before this one, that God’s foolishness is wiser than the wisdom of the world. So Paul is not saying that there is no wisdom here in this apparent crude simplicity. It is, he says, “God’s wisdom, secret and hidden, which God decreed before the ages for our glory.” This wisdom of God, secret and hidden, says Paul, is not understood by any of the rulers of this age, for if they had understood it, they would not have crucified the Lord of glory.

Now I want you to note that when Paul says that it is secret and hidden, he does not say that God actively and intentionally hid it. Something can remain secret and hidden because we become blind to it, and that doesn’t mean that God is at fault for hiding it from us. Elsewhere too, Paul speaks of “the plan of the mystery hidden for ages in God who created all things.” (Ephesians 3:9) That’s hidden in God, not hidden by God. And Matthew’s gospel says that Jesus’s teaching proclaimed “what has been hidden from the foundation of the world.” (Matthew 13:35)

So what Paul seems to be saying is that the most important mysteries of the universe were hidden from us by our own expectation that they should be too complex and sophisticated and profound for ordinary people to easily grasp. Looking in all the wrong places, we totally missed the point. We came up with all manner of highfaluting theological theories, but really, the fundamental mysteries of the universe are nowhere near so complicated.

The fundamental mysteries of the universe are simply given to us, Paul says, as gifts. God has given us Jesus, as a gift. God has given us the Holy Spirit, as a gift. God has given us love and mercy and hope, as gifts. And all the gifts reveal the same thing, the great mystery that has been hidden by our own blindness since the foundation of the world, the great mystery that God loves us, deeply and passionately and overwhelmingly; the great mystery that God really really likes you; that God looks at you and bursts into love-song crying, “Yes! How wonderful you are. Come dance with me, you who are beloved from the foundation of the earth.” God looks at you and thinks, “I love you so much I’d willingly die for you.”

Oh no, we say. It can’t be that simple. That’s child’s stuff. Surely we need a complex religious system full of sacred rituals and profound liturgies; surely we need to know how many angels can fit on a pin-head and how many wings the seraphim have; surely we need a religious legal code to meticulously define the line between holiness and sinfulness and police it fiercely. Has not the Torah given us 613 commandments and not one jot or tittle shall disappear from the law until all is accomplished? Isn’t that what Jesus said?

Yes, says Jesus, but all is accomplished, and all that is important in those 613 commandments, I can sum up in just two: love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul and mind, and love your neighbour as attentively as you love yourself. That’s all. If you accept the gift and know yourself deeply and truly beloved that’s all you need. What? Who is your neighbour? Well, love your enemies. That ought to cover it. Look, if it still not clear, just follow me. Do as I do. Love everyone else the way I have loved you. That’s all there is to it. Just love. They will know that you are my followers by your love. Not by your grasp of clever atonement theories. By your love.

The deepest mysteries of the universe come down to one simple word that even a child can understand. Love.

Or rather than “even a child can understand”, I might say perhaps only a child can understand. The rest of us seem to be pretty good at missing it. So good that when we saw perfect love, we crucified it. And when we realised what we had done, we went right back to trying to turn it back into something impressively clever and complicated. We tried to fit the crucifixion itself into complicated theories of atonement and justification and divine justice, and it is possible to do that, but it nearly always misses the point, which is love, love, love.

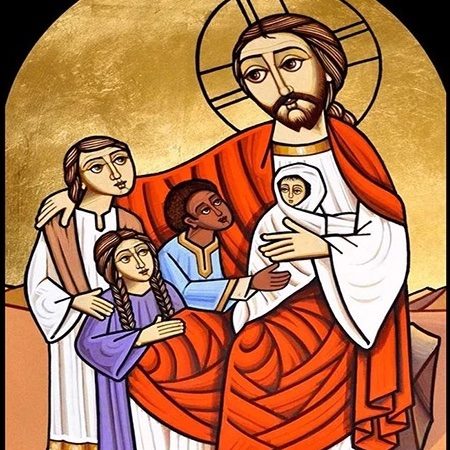

We are thinking a bit about how this relates to our children tonight, because in a few minutes we will be celebrating the back-to-school blessing with them, but often we think too much about what we are teaching them instead of asking what we might be needing to learn from them. And my comment about children often understanding the wisdom of God and the teachings of Jesus better than adults is not meant to be tongue in cheek. Yes, we are passing the faith on to them, but we need to be at least as open to receiving it from them.

We heard Jesus tonight talking about us being the light of the world, and letting our light shine before others, and that’s certainly about recognising the positive influence we can have on others, young and old. And he went on, in his comments about nothing disappearing from the law and the prophets, to talk about what we teach others to think and do.

But teaching, at its best, is a cycle, and we can learn a lot from listening to how our teaching and our example is received by those we are passing it on to. What do the children among us hear and understand as we try to teach them a more liberating understanding of the gospel that says it is not all about rigid law keeping but about getting caught up in the love and grace of God?

It is quite illuminating to hear Acacia talk about this, as I’m sure a few of you have. I’m picking Acacia because she is the one young adult here who was part of this church for her entire childhood, so many of us were there through all or much of her childhood, and it was us that she was watching and listening to as she learned the faith.

I hope I’m not misinterpreting her here, but I think she would say that although she did gain a liberating and grace-filled understanding of the gospel here, we are not nearly as good at explaining it as we like to think we are. Actually, I’ve heard Rita say something similar. She didn’t grow up here, but her first serious encounters with Christian faith and church culture were here, so both of them were watching and listening to us.

And what they both found is that most of us are a lot better at explaining what the gospel isn’t than what it is. That is, we try to describe it by contrasting it with something else, with the kind of faith systems that many of us grew up with, something that was more rigid and oppressive and frightening. And for us who grew up with that kind of thing, thinking about the contrast is a helpful way in. But it was not nearly so helpful for Acacia or Rita, because they weren’t carrying the scars that we were. Waxing lyrical about how different it is from something they’d never encountered didn’t shed much light for them.

It seems that we knew how the gospel might be good news to those who were oppressed by abusive forms of religion, but we weren’t nearly so good at helping Acacia and Rita to understand how it was good news for them! Thanks be to God, it didn’t all depend on us!

But let it be a reminder to us to listen to these children as they grow, and don’t think that the teaching and learning is all flowing one way. If we listen to what they are picking up from us, we can learn a lot about the strengths and weaknesses of our own understandings. And we can certainly learn about not trying to turn it all into something too clever and complicated when nearly all of what really matters is just love, love, and more love.

As it is written,

“What no eye has seen, nor ear heard,

nor the human heart conceived,

what God has prepared for those who love him” –

these things God has revealed to us through the Spirit; for the Spirit searches everything, even the depths of God, and there in the depths of God, all is love. Love, freely given as a gift, fully revealed in the crucified Jesus. Love that endures everything and stops at nothing. Love, so simple that many scorn it as childish and turn away. Love. The beginning and the end. Love.

0 Comments