A sermon on Matthew 1: 18-25 by Nathan Nettleton

This is an odd time of year for us. Next week will be even odder. There is a kind of uncomfortable feeling of disconnect. A feeling of being out of kilter, or perhaps just confused. All around us, the celebration of Christmas festivities is in full flight, but there are no nativity scenes in here, let alone trees or baubles, and we haven’t sung a Christmas Carol yet and we won’t until Friday night. The closest we’ve got was singing “Joy to the World”, but that’s actually an Advent hymn with no Christmas references in it at all.

One of the things that makes this feel so odd is that we are all kind of living double lives at the moment. When we are here in the church it is not Christmas yet, but the rest of the time, we are just as involved and just as dominated by it as everyone else. I know that in my house there is lots of wrapping of presents going on, and there’s family functions, working out what festive food we are supposed to be contributing to the Christmas dinner, searching for lost recipes and Kris Kringle allocations, and a hasty trip to the shops. And then we walk in here and there is not a sign of Christmas to be seen. It is as though we are in denial, pretending it is not happening.

Next week will feel even more odd. For the next two Sundays we will walk past the discarded and drying out Christmas trees on the kerbs, sure and certain signs that Christmas is over for another year, and then walk in here and begin singing Christmas carols, telling stories of the birth and infancy of Jesus, and praying before the icon of the Nativity. And if you’re anything like me, one part of your brain will be wondering what the neighbours are thinking as they hear the sounds of our Christmas carols wafting through the walls on January fifth. “What are these weirdos doing? Wasn’t six weeks of carols in the shops enough for them that they don’t even know to stop when Christmas is over?”

I know for me it feels a little odd each year, and even a bit awkward and embarrassing. So what do we think we are doing and why? Are we just being obstinate and perverse? Or worse still, do you just have a pastor who is an obstinate and perverse liturgical fundamentalist who is vainly trying to resurrect an obsolete practice of the twelve days of Christmas and inflicts this awkwardness on you each year?

I’ll have to leave that latter question for you to answer yourselves, but what can be said in support our practice? I’ve been reflecting quite a bit on the feeling of the oddness, the weirdness of it. Especially the oddness that is coming next week. And I think there is something quite important, quite valuable in it. And it’s something that I think makes some connections with the experience of Joseph that we heard about in our gospel reading a little earlier.

You see, the point of not observing Christmas in the church until the traditional twelve days is not primarily a matter of being fundamentalist about the calendar. We are not just doing a variation on those Christmas in July parties that some people have, planning to do the same thing at a different time for the obstinate purpose of being right about the niceties of the calendar.

Instead, the point is actually the question of whether it is the same thing. Is what we are going to try to do next week just the same thing that everyone else is doing this week and we’re just out of step by a week or two? Or are they in fact two quite different things which are more easily understood and more fully experienced if they are kept apart from one another?

Historically, there were festivities at this time of the year in much of the world, and certainly in most of Europe, before the creation of the Church’s celebration of Christmas. The older festivities were mostly associated with the Solstice – in the northern hemisphere, the winter solstice, the longest night of the year. The decorated trees and Santa Claus and many of the festive foods and decorations all come from various solstice traditions and originally had nothing to do with the Christian faith or the Church.

Now there is some dispute among the historians as to whether the Church invented Christmas in order to try to Christianise these solstice festivities, or whether the dating of Christmas at the same time was a coincidence, but whether it was planned or not, the two became merged and the various symbols mixed up together. So now everyone thinks the solstice tree is the Christmas tree and we are a bit confused about what it has to do with baby Jesus but we’re sure there must be some connection. The only connection is on the calendar.

But in the last century, with the massive commercialisation of this Christmas/Solstice celebration, the shopping patterns have actually shifted the festival on the calendar, so now it ends on Christmas Day, whereas the Church’s Christmas season has always started on Christmas Eve and ends on the Feast of Epiphany on January sixth. So the two merged festivals have actually grown apart again, at least on the calendar.

But, it is not as simple as that, is it? Because they have both pinched each other’s symbols and taken them with them. The Solstice Christmas has pinched the nativity scenes and angels and nativity carols, and it is quite common to see Solstice trees and baubles and even Santa Clauses in churches. And in most people’s minds, including most of us, it is impossible to separate the two. A scrambled egg can’t be unscrambled, so to speak.

So many churches have done the obvious thing and simply gone with the flow. They are celebrating the Nativity of our Lord now, and next week they won’t be. It will be over. And I have absolutely no doubt that that would be easier. It would feel a lot less odd. There wouldn’t be that awkward and slightly embarrassed feeling when we’re still singing carols into January. The question is, at what cost?

Just as you can’t make a pavlova with a scrambled egg, I think it is pretty near impossible to make any sense of the sacred celebration of the Nativity when it is all scrambled in with Solstice trees and Santa Clauses and shopping frenzies. And while I don’t think we have a hope of getting nativity symbols out of the Solstice festivities, we can observe Christmas at its traditional time and so experience it on its own as a different thing.

But I do acknowledge that the difficulty of that is that by the time we are singing Christmas carols in the church, they’ve been done to death in the shops and we can feel sick of them. And everyone else is sick of them too, which is why they think we’re so weird singing them in early January. And it is because everyone else thinks they are the same thing that we feel awkward and embarrassed. We don’t feel weird celebrating Pentecost when no one else does, precisely because no one else does. But at Christmas, it looks and feels as though we are just confused and mistaken, so we get more self conscious about it.

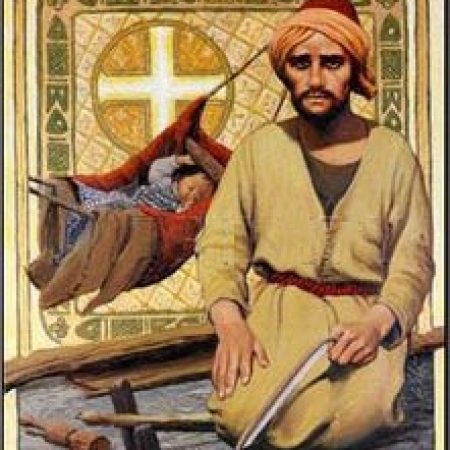

Which is where Joseph comes in. You were wondering if I was ever going to get to him, weren’t you? Joseph also had to make a tough choice between going with the expected flow, or being faithful and feeling on the outer. He too had to deal with awkwardness and self-consciousness in order to wait for what God was calling him to. And it was a lot more costly to him.

When Joseph found out that his fiancé, Mary, was pregnant, his first impulse was to do the expected thing in the gentlest and most decent way he could, and that was quietly call off the engagement and sever ties with her. Joseph was no gynaecologist but he knew how these things happened, and he since he knew she hadn’t slept with him, clearly she had been sleeping with someone else, so he wasn’t going to go through with marrying her. No one would have expected any different of him.

Of course, even apart from the sense of hurt and betrayal he would be feeling, Joseph had his own reputation to think of, and sticking with Mary was a no win for him. If it became known that his girl was carrying someone else’s child, he’d be humiliated, and if it was thought that the child was his, his reputation as a respectable and honourable young man was shot since they weren’t married yet. Pre-marital sex might not cause much angst nowadays, but it sure did then. Either way, he loses.

So the only right thing for him to do is sever ties with Mary, and his only choices are whether to make a public issue of it or not. If he does, he draws more attention to his own embarrassment, and there is a possibility that Mary will be stoned to death. He’s not up for that, so he opts to make the best of a bad situation and cut off the betrothal quietly. Mary will still be disgraced and be left pretty much unmarryable, but if she keeps herself and her illegitimate child behind closed doors, she should at least survive.

But then a messenger from the Lord turns up in a dream and tells Joseph that it was God who impregnated his girl, and that he should go ahead and marry her. Now I don’t know about you, but if I’m Joseph and someone turns up and confesses to having impregnated my fiancé, I don’t much care if he happens to be God, I’m not happy about it, and I’m certainly not taking orders from him. Especially when those orders are essentially about covering up for him, shouldering the blame myself, and raising his illegitimate child as though it was my own. “You caused the problem, God. Fix up your own mess. Count me out.”

But Joseph seems to be a man of rather more nobility of spirit than me, and he’s up for the challenge of cooperating with whatever the hell it is that God is up to here.

So for Joseph, what he learns in the dream is that God is offering him what he wanted originally, that is Mary as his wife, but now she is going to come to him as, in the eyes of the society around them, tarnished goods. And so, if Joseph is going to be faithful to God and faithful to Mary, he has to endure the awkwardness, the embarrassment, the self-consciousness, even humiliation.

He has to wait; to wait and hope and pray and trust that there might be some value in this, some good come out of it to make it all worth while. And his faithful waiting and his bearing of the social cost is the proof of the integrity of the man that we have remembered all down these years. He did what was right, even when it looked all wrong to everyone around him.

Tuesday night’s Christmas Eve service will feel all right, but by next Sunday, nativity scenes and Christmas carols will feel like tarnished goods, ready to be left in the gutter with the trees. They will have been so prostituted in the market places for so long that we will feel awkward and stigmatised to be any longer associated with them.

But perhaps it is only then, under the weight of that embarrassment, that we, with Joseph, will have any chance of being captured and liberated by the scandalous truth that is Emmanuel, God with us. And I reckon that’s worth waiting for.

0 Comments