A sermon on Luke 20:27-38 by Nathan Nettleton

Have you noticed that we use the word “alive” in two different ways? When we say things like “this time last year he was still alive”, or “she’s been badly hurt, but she’s still alive” we mean something quite different from when we say, “she is so much more alive when she’s here”, or “you could see him coming alive that summer”, or “I didn’t know I was alive until I met you.”

We could probably refer to these as the literal and the metaphorical meanings of the word. But tonight I want to consider whether we’ve got them back to front, and whether we mostly fail to comprehend the life that God is calling us to and offering to us, precisely because we mistakenly think that the primary meaning of being alive is simply not being dead. What if the real meaning of being alive is so different and so mind-bogglingly huge and powerful that the question of whether or not you are dead is utterly irrelevant and insignificant?

At our local All Saints service last Tuesday night, my sermon prompted quite a bit of conversation afterwards about the differing views of what life after death might mean. It wasn’t until later when I turned my mind to preparing for this sermon that I realised that the same question was front and centre in the gospel reading for tonight.

In the All Saints sermon I said that the most popular view of life after death is that death is just a horizon over which we pass to an immediate continuation of life without a body somewhere else, but that the more strongly attested view in the New Testament is that we die, body and spirit, and stay dead until the day of resurrection when God will raise everyone to new life.

Now when I single out the New Testament there, you may be wondering what the older Hebrew scriptures have to say on the topic. Well, exactly that question is being asked in tonight’s gospel reading, so let’s take a look at it and see where it might take us.

This is one of a series of stories of different groups coming to interrogate Jesus after he arrived in Jerusalem. Those who have got it in for him are ganging up and taking it in turns to try to trap him into incriminating himself with their tricky questions. The chief priests and scribes have a go, the Pharisees have a go, the Romans have a go, and in tonight’s episode, the Sadducees have a go. Luke introduces them by telling us that the Sadducees don’t believe in a resurrection.

The Sadducees were also the wealthy upper class of Jerusalem society, and when you’ve got it made in this life, you tend to be happier thinking that you are being rewarded by God here and now. Funnily enough, the idea of an afterlife in which God might turn the tables and reward everyone else is a lot more attractive to everyone else than it is to those who are winners at the moment.

But the Sadducees prided themselves on being entirely biblical in their rejection of belief in the resurrection of the dead. They only recognised the first five books of our Bible, which they called the books of Moses. All those other books like the prophets and so on were to them later innovations full of dubious speculations.

So for the Sadducees the only questions were, do the books of Moses tell us that there will be a resurrection, and if not, do they teach instead a contrary view? The first question was the more definitive. They believed that Moses was the ultimate prophet and the friend and confidant of God, so if something as important as a resurrection of the dead was real, God would have told Moses, and Moses would have told us. If we haven’t heard it from Moses, then it clearly doesn’t exist.

Since nobody was claiming that Moses talked about a resurrection, it was their second “proof” that they bring to Jesus. “Teacher, Moses wrote for us that if a man’s brother dies, leaving a wife but no children, the man shall marry the widow and raise up children for his dead brother.” Even before they expand on this with their story about the seven brothers and one wife, this is quite a clever argument.

The so-called Levirate law is based on the assumption that the only way you live on after your death is through your children. Biologists will tell you that pretty much every life form on earth works on this assumption. Creatures seem to be genetically coded to compete as hard as they can to pass on their genes to the next generation. The Levirate law then was intended to ensure that if a married man died childless, his name, his memory, and thus his life, would not be lost from the world. The Sadducees are quite right to point out that this law, given by Moses, would have been pointless if the man was going to live on in some other way. Thus, they concluded, not only did Moses never teach us that there would be a resurrection, he taught us this law that clearly assumes that there won’t be.

Their rather sarcastic story about the seven brothers each dying and passing on the one wife was quite clever too. Jews of Jesus’s day would have immediately been reminded of a story of the seven Maccabean brothers from the book of Tobit. Tobit was one of those much later books that the Sadducees distrusted, and it clearly did teach that the dead would be raised. So the Sadducees have worked the double whammy, ridiculing a popular resurrection story while showing that it was at odds with a law handed down by Moses. Checkmate.

So to summarise so far, at the time of Jesus we have two different views of life after death. The older one was the genetic heritage one: you die but your life is passed on through your children. Still a widely held view today, I think you’ll agree. The newer one was that you died, but that at some point in the future God would raise the dead to new life. Which one you believed depended on whether you thought God’s revelation ended with Moses or continued in the prophets. Your social status in this life may have influenced you too.

The idea of simply leaving your body behind and passing over to a spiritual life somewhere else is not on the table yet. To the Hebrew mindset, the idea of a human life apart from a body simply did not compute. Life is all about the body. Without one, there is no life. The idea of a soul leaving the body and living on separately emerges later still, from Greek philosophy. Like some other Greek concepts, there are hints of it in the New Testament, but it is clearly not what this thoroughly Hebrew joust between Jesus and the Sadducees is about.

Now, on to Jesus’s response. Firstly, don’t fall into the common trap of thinking that Jesus is stating that the resurrection life will have no place for the deep intimacy and love of marriage. He is not talking about marriage as an intimate relationship. He is addressing the question of the Levirate law – marriage as a means of passing on your life by procreating. Elsewhere, Jesus uses intimate loving marriage as the major metaphor for the resurrection life, the marriage of heaven and earth.

So onto the main point. What is Jesus saying about life beyond death? Luke softens Jesus’s response to the Sadducees. He leaves out the rather blunt and even rude opening line, reported by Matthew and Mark, where Jesus says, “You are wrong, because you know neither the scriptures nor the power of God.” Sounds quite fundamentalist, doesn’t he?! “You are wrong!”

Jesus says that they don’t know their scriptures, and he proceeds to break out of their apparent checkmate, not by arguing for the validity of the later scriptures, but by quoting from the scriptures they accept, the books of Moses. And not just some obscure passage. The story of the burning bush. You can’t get more solidly Moses than that. “The fact that the dead are raised is shown by Moses himself,” says Jesus, “for he speaks of the Lord as the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob. Now he is God not of the dead, but of the living; for to him all of them are alive.”

And in the verse beyond where we finished tonight, they concede that he has spoken well, and we are told that they no longer dared to ask him any more questions. They did continue to participate in the conspiracy to cut him off from the land of the living though.

But there is a complication for us here, isn’t there? We’ve grown up with the Greek view that souls live on without bodies, and despite Jesus saying that Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob all being alive to God shows that the dead are going to be raised, we would more naturally see it as evidence that they are living on somewhere else now, prior to the day of resurrection. To us it sounds like better evidence for the Greek view, doesn’t it?

But if Jesus didn’t see it that way, what are we to make of it? Perhaps Jesus is telling us that we are wrong too, because we do not comprehend the power of God either.

To be fair to the Sadducees and the disciples and everyone else, what Jesus was trying to say was probably incomprehensible to everyone prior to his resurrection. And even after meeting the crucified and resurrected Jesus we still struggle to get our heads around it. I’m not for a moment pretending that I’ve got it all worked out and that I can spell it out simply for you now and we’ll all go home with an A+ in resurrection theory. But let’s see if we can catch some glimpses together by trying to hear what Jesus is saying here in light of our subsequent experience of his resurrection.

The difference between Jesus’s resurrection and the resurrection of the dead that we say we believe in when we sing the creed is primarily one of timing. Jesus is the first fruits. He is the only one who has been resurrected yet, but we will all be resurrected as he has been.

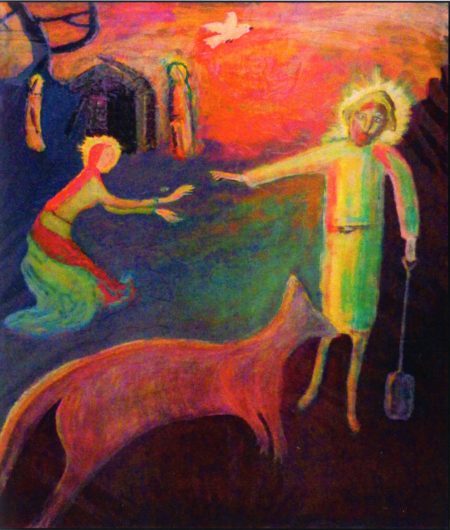

Now this is where I get back to my opening point about aliveness. The aliveness we encounter in the crucified and risen Jesus is so far beyond merely not being dead that it is right off the scale. In Jesus we encounter an aliveness that breaks open tombs, that breezes through the locked doors of fear, that drops doubters to their knees, and erupts with overwhelming love and mercy for betrayers and deniers and conspirators and crucifiers alike. In Jesus we encounter an aliveness that makes everything we have ever known look like nothing more than death warmed up.

Most importantly and mind-bogglingly, we encounter an aliveness that cannot even be defined as the opposite of death. We think that alive is the opposite of dead, but Jesus is so extravagantly alive that he can be dead at the same time and it doesn’t make a jot of a difference. You see, the risen Jesus is still the crucified Jesus. He presents himself to us, still bearing fatal wounds. He is not just a dead man walking, but a dead man who is so bursting with life that being dead does not pose the least threat to his being alive. He is far too alive to let a little thing like being dead worry him.

To us, claiming to be simultaneously alive and dead seems impossibly contradictory. To God – to the crucified and risen Jesus – it is no more contradictory than saying “I’m alive and I’m left-handed.” They are so non-contradictory as to seem quite irrelevant, unrelated.

Do you see why I’m saying that for God, the primary literal meaning of the word “alive” is the one we think of as metaphorical, the one that has no reference to death but speaks of an exuberant and overflowing and wonderful quality of life. That’s what being alive means. That’s the aliveness we encounter in Jesus and taste here at his table. And that’s the aliveness that is the promised destiny of each and every one of us.

So that opens up the possibility of understanding what Jesus says about Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in a quite different way. He is not saying that they are not dead, but that being dead doesn’t diminish them in the least. God relates to them in their aliveness, not in their deadness.

I don’t have time to rehash everything I said on Tuesday night about what this might mean for what happens to them and us between our deaths and the day of resurrection. You can go back and read that sermon if you wish. But in a nutshell, I am suggesting that when we die, we don’t go off as free-floating souls to live somewhere near God, but that we live “in” God, our lives held securely in trust in the unfading memory of God, so perfectly remembered that we continue to be loved just as fully and constantly and extravagantly as we were before our deaths and as we will again know ourselves to be on the day of resurrection.

Now, as I acknowledged before, I make no claim to certainty that I’ve got all this nailed. At best I’m making biblically informed speculations. We’re standing on tippy toes and trying to make some sort of sense of the resurrection life that we’re glimpsing and tasting. If you still find the idea of slipping away from your body to play harps in the clouds more helpful, go with it. None of us will be saved by getting an A+ for theory of resurrection.

What matters, and what will save you and set you on the pathway to full aliveness, is to find yourself infinitely beloved with a love that renders death utterly powerless; a love so fierce and tenacious that even an agonised death hung up on nails cannot begin to dim it but instead fans it to an even brighter flame.

You should be able to catch another glimpse or fragrance or taste of that love here tonight, in the body of Christ gathered around this table and the body of Christ broken and shared from this table. And if you respond, it will draw you on further into the radical aliveness that you were created for. And when you have been drawn all the way in and are completely immersed in the love and life of God, it will no longer matter which side of death you are on because everything will be bursting with aliveness and overflowing with love without limit.

0 Comments