A sermon on Acts 7:54-55 by the Revd Dr Keith Clements, 10 May 2020

A video recording of the whole service, including this sermon, is available here.

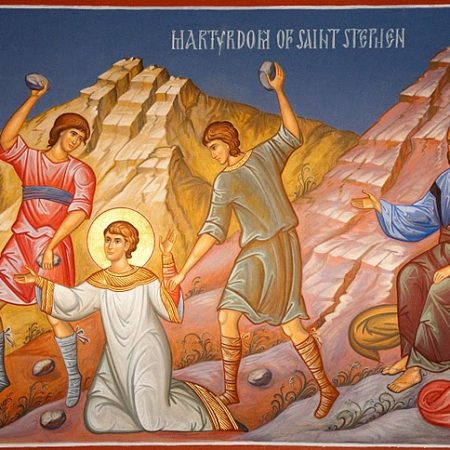

“When they heard these things, they became enraged and ground their teeth at Stephen. But filled with the Holy Spirit, he gazed into heaven and saw the glory of God and Jesus standing at the right hand of God.” (Acts 7:54-55).

Martyrdom involves suffering even unto death. But, no less important, the martyr sees what other people may not be seeing, and opens their eyes to it.

In the year 156 AD, Polycarp, the aged bishop of the church at Smyrna in Asia Minor (Turkey today) was put to death. During a pagan festival he was seized by a mob and brought before the Roman official, Statius the Fourth by name, who urged him to renounce his faith and burn incense to the Emperor as to a god, and so save his life. Polycarp refused, saying, “I have followed Jesus Christ for over 80 years. He has never failed me, why should I now fail him?” Offered the choice between being thrown to the lions or tied to the stake and burnt, he chose the latter and so died in the flames. In great sorrow, yet with a measure of pride, the Christians of Smyrna wrote to other churches in the region recording Polycarp’s death in these words: “He was arrested by Herod in the Chief Priestship of Philip of Tralles, in the proconsulship of Statius the Fourth, but in the everlasting reign of Jesus Christ.” The everlasting reign of Jesus Christ: kings and governors may rule for a time and during their time may impose their rule. But Jesus Christ reigns for ever. No doubt inspired by the first Christian martyr Stephen more than a century earlier, Polycarp and his people had seen heaven opened; glimpsed the glory of God; seen Jesus, crucified and risen, at God’s right hand, the one utterly to be trusted, the one to obeyed above all others.

Yes, the martyr suffers but more to the point sees.

The word martyr itself means, first of all, not someone who is put to death, but “a witness”. In the early years of the church it did come to mean especially those whose witness brought them to death, as in Stephen’s case. But we notice from the account in Acts that what finally drives Stephens’s hearers mad -his hearers in the council of elders in Jerusalem– is his witness to what he sees: in the opened heavens, he sees the unspeakable majesty of God, and Jesus, glorified and made yet more glorious and victorious by the scars in his hands and feet and his side. It’s important that we remember this, because we’re apt to dwell on the sufferings of the martyrs, the pains they went through, the death they died. And that’s not always a very healthy interest. I remember as a boy discovering on the shelves in my father’s study a book called Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. Written in the 16th century, it was a famous account of the persecution of Protestants in England under Queen Mary Tudor who sought to reimpose Roman Catholicism in England. It described in great and graphic detail–and this copy had some lurid drawings too– the sufferings and tortures endured by both men and women who were burnt at the stake or torn apart on the scaffold. It was written to inspire a like heroism among the next generations of Protestant believers. But as an impressionable youngster, I found myself in danger of becoming morbidly hooked on the cruelties. It could almost be read as violent porn.

But the martyrs don’t only suffer, they see; and it’s what they see that matters. The true martyr isn’t witnessing to his or her own faith and heroism, saying “Look at how I suffer, how courageous and faithful I am being.” Indeed, today to call someone a martyr can be a subtle criticism. “Don’t martyr yourself”, we say to someone who’s making themselves unnecessarily busy whether in the kitchen or in the office, or deliberately courting unpopularity. When I was a student at Cambridge University, one hot Sunday afternoon a couple of ardently evangelical students went down to the riverside pub where a lot of students and townspeople were enjoying a drink sitting on the parapet just over the water’s edge, and set about preaching to them. It was hardly surprising that their preaching didn’t last long, and soon they were making their way back to their college, dripping wet. Hearing the story, some of us admired their courage and devotion to the Lord. Others were not so sure, and more than a little suspicious that intruding on people’s pleasant Sunday afternoon by the river was intentionally provoking a kind of martyrdom.

The ultimate in this way of thinking is to advertise even one’s own defiance of death. It’s the desire for admiration of the suicide bomber who is prepared to blast himself to death along with innocent people enjoying a pop concert, so that among his fanatical friends he can gain glory as a martyr as well as a ticket to paradise. That death-wish has not been confined to Islamic extremism. Very soon in the early Christian centuries the church fathers warned against those who sought martyrdom as a way to glory. True martyrdom is not witness to oneself, but to the one holy God and God’s glory. Nor should we romanticise martyrdom as a way of boosting the reputation of Christianity and of our church, putting up a roll of honour publicising our stock of heroism. It’s interesting that in that ancient hymn of praise we know as the Te Deum Laudamus, we sing about the “noble army of martyrs”, but only after the glorious company of the apostles and the goodly fellowship of the prophets; and we are not signing in praise of apostles or prophets or martyrs but with them and with “the holy church throughout all the world” we are acknowledging and praising the one holy, holy, holy Lord.

No-one knew this better than the one whom we list as one of the modern martyrs, and about whom I’ve been asked by one or two of you to say a bit more today: Dietrich Bonhoeffer. It was almost exactly a month ago today that many of us were commemorating the 75th anniversary of his death, on 9th April 1945, at Flossenbürg concentration camp in Bavaria. There is certainly much to admire and to be inspired by in the story of Bonhoeffer, the brilliant young theologian and pastor of the Confessing Church which had resisted the Nazi attempt to take over German Protestantism; the one who went much further than most Christians did in their resistance to the regime by joining in the conspiracy actually to overthrow Hitler, an attempt which tragically culminated in failure on 20th July 1944. To visit the memorial at Flossenbürg is a very moving experience. You can stand in the bare courtyard where early on that April morning Bonhoeffer and six others in the conspiracy were hanged. For some years there has circulated a rather sanitised account of his death, supposedly written by a camp doctor; about Bonhoeffer kneeling to pray at the foot of the gallows, and then going to a very quick death. More has been uncovered recently about what actually happened that morning. The Nazi SS guards at Flossenbürg were among the most sadistic of Hitler’s henchmen. Not only would they never have allowed acts of piety, but the deaths that morning were not quick drops. They were barbarically slow and repeated strangulations. What an end, for such a life of just 39 years. What a martyrdom that was, to both horrify and move us. How tragically apt a fate for the one who in his great book on costly grace and discipleship, wrote “When Jesus calls us, he bids us come and die.”

No-one knew this better than the one whom we list as one of the modern martyrs, and about whom I’ve been asked by one or two of you to say a bit more today: Dietrich Bonhoeffer. It was almost exactly a month ago today that many of us were commemorating the 75th anniversary of his death, on 9th April 1945, at Flossenbürg concentration camp in Bavaria. There is certainly much to admire and to be inspired by in the story of Bonhoeffer, the brilliant young theologian and pastor of the Confessing Church which had resisted the Nazi attempt to take over German Protestantism; the one who went much further than most Christians did in their resistance to the regime by joining in the conspiracy actually to overthrow Hitler, an attempt which tragically culminated in failure on 20th July 1944. To visit the memorial at Flossenbürg is a very moving experience. You can stand in the bare courtyard where early on that April morning Bonhoeffer and six others in the conspiracy were hanged. For some years there has circulated a rather sanitised account of his death, supposedly written by a camp doctor; about Bonhoeffer kneeling to pray at the foot of the gallows, and then going to a very quick death. More has been uncovered recently about what actually happened that morning. The Nazi SS guards at Flossenbürg were among the most sadistic of Hitler’s henchmen. Not only would they never have allowed acts of piety, but the deaths that morning were not quick drops. They were barbarically slow and repeated strangulations. What an end, for such a life of just 39 years. What a martyrdom that was, to both horrify and move us. How tragically apt a fate for the one who in his great book on costly grace and discipleship, wrote “When Jesus calls us, he bids us come and die.”

But this, again, can lead us to focus on what he suffered, at the expense of what he saw. Yes, at Flossenbürg it’s moving to stand in that execution yard where he died. But about 200 metres away there’s a rather nondescript building, of grey concrete. It was the camp laundry where the hastily-convened court-martial was set up the night of 8th April to deal with those remaining conspirators. It was a travesty of justice, cobbled together to give a semblance of legality for those carrying out Hitler’s final order to eliminate them. Six concrete steps lead up to the door of the building. As I mounted those steps, I wondered, what was in Bonhoeffer’s mind as he went up them that night? He’d come to make his final stand and to hear his conviction of treason be read out and his sentence of death pronounced. That, as much as the execution yard, was his place of martyrdom, for by standing there silently and unflinchingly he was remaining true to what he had seen of the opened heaven, where stands the one who is everlastingly the only true Lord of heaven and earth, the only one wholly to be trusted, the one to be obeyed above all others.

What he saw, and had been seeing for years, he saw much more clearly than most of his generation did. What he saw was uncomfortable. I wonder, as he went up and afterwards when he came down those steps, did his mind go back to thirteen years earlier when he was a young pastor and lecturer in Berlin, when he preached a sermon on seeking “the things that are above, where Christ is, seated at the right hand of God”(Colossians 3:1-4)? That was in 1932, the year before Hitler came to power. But Bonhoeffer sensed what was coming, and said: “…we should not be surprised if for our church… times will come again when the blood of martyrs will be required. But”–he went on”–this blood, if we really still have the courage and honour and faithfulness to shed it, will not be as innocent and untarnished as that of the first witnesses. On our blood would lie great guilt of our own: the guilt of the worthless slave, who is thrown into the outer darkness.” Bonhoeffer was warning against thinking that the church is always simply the innocent community threatened by the wicked, pagan world, as it was in its early days, the time of Polycarp. Christianity, he saw and said, was no longer so innocent. In the Western world at least, it was fatally compromised by the world, and was itself infected by the forces of material greed, of class pride, of racism, nationalism, and militarism. Modern martyrdom has to be a repentant martyrdom. Would he say anything different today? Let’s beware of those who say from time to time that” a bit of persecution would do the church good”. Quite apart from that being untrue, the church has to confess its own acquiescence and complicity in unrighteousness, the things of earth rather than the things of heaven, where Christ is, at the right hand of God: justice, peace, mercy, compassion and forgiveness. Christianity has its share of responsibility for bringing about what is threatening the church. That became very evident from 1933 onwards, and we should ask, might the same be true today?

Illuminated by the light from the opened heaven, in his time Bonhoeffer saw through the false allure of what passes for “patriotism”. Patriotism, loving your country, can take various forms. Gratitude for your country’s scenery, its language, its customs, its food, all the ways it has nurtured and enriched you, is natural and fine. Cheering your side on in the stadium is fine too. If I was to go with some of you to the MCG to watch an Ashes test match doubt relations between us would become a little strained during the match, as we exchanged pithy comments about the state of the pitch or the eyesight of the umpires, But afterwards we’d be best of friends again over a beer or two; well, probably. But patriotism can get a bit stupid. The writer C.S. Lewis tells of a conversation he once had with an elderly English clergyman. Lewis remarked to him that every nation thinks its men are the bravest and its women the fairest, and the cleric said, “Ah yes, but in England it’s true”. As Lewis says, that man was an old fool. A dangerous one too, for once you’ve reached that point there’s nothing to stop you sliding into believing that loving your country means denigrating other countries, and that your own is beyond criticism. That’s what Stephen found that day in Jerusalem. What enraged the council was that he gave them a potted history of Israel which consisted of one long slating of the country’s unfaithfulness to God. The next fatal step is to believe that your country has a right to behave as if others don’t matter or shouldn’t even exist if they stand in your way. Build your walls against them, cow them with your arsenals of terror. Ultimately, devise your “final solutions” of genocide.

Bonhoeffer, years before he died under torture at Flossenbürg, was already the martyr, the witness, who saw all this, and yet more. He looked at Germany and the world of his time exposed to the open heaven. Like Stephen centuries earlier, he gazed into heaven and saw the glory of God and Jesus standing at the right hand of God, and saw that this is the kingdom and the power and the glory that has to be sought and obeyed on earth, for the world and all that is in it belongs to God and to his Christ, not to the powers that would claim it and destroy it.. He called upon his church and his people to honour and worship that glory, instead of seeking a glory of their own, whether a glory of themselves as individuals or a glory of their country and its supposed greatness. This was the true patriotism of one who in recognising the supreme lordship of Jesus Christ could love his country in a way undreamt of by those who thought their country was only worthy of love if it was all conquering, all-possessing, all-consuming, made “great” again.

These past few days, we in the UK and doubtless many of you in Australia, have been commemorating the end of the war in Europe in May 1945, just a month after Bonhoeffer died. It’s a worthy commemoration. Bonhoeffer himself said several times during the war that as well as working towards the overthrow of Hitler he had to pray for the defeat of his country, as the only way to preserve hope for civilisation. It’s also natural that at this time of crisis and disaster wrought by the Coronavirus pandemic we should recall how with faith and determination our people emerged from war 75 years ago. It is indeed now a frightening time, not just because of the threat of disease, but because so much is shifting in unforeseen ways on the world scene. But if we really want a hope for the future we cannot just relive the past, trapped in a patriotic nostalgia, singing “We’ll meet again” and comforting ourselves with only partially true versions of our history. Beyond the rising and falling of nations we need to see as the prophets and martyrs saw, and look for the everlasting reign of God and his Christ; pray to discern the directions in which God will call us, and the new forms that living together in justice and peace on this fragile earth will require. The opened heaven will shed on the earth a new light. The last known words of Dietrich Bonhoeffer on being taken away to Flossenbürg were words of hope. “This is the end, for me the beginning of life”; and a message for his great English friend Bishop George Bell: “Tell him, that with him I still believe in the reality of our universal Christian fellowship which rises above all national interests and conflicts, and that our victory is certain.” Or, we might say, “Filled with the Holy Spirit, he gazed into heaven, and saw the glory of God, and Jesus standing at the right hand of God.” So, by God’s grace, may we.

4 Comments

We have had the privilege of having Keith preaching for us in the past, so it was no surprise that he was one of the preachers people wanted to hear from again during this time when lockdown has given us the opportunity to have international visiting preachers without having to wait for them to visit our shores. He certainly didn’t disappoint us!

It is always a privilege to hear about the life and witness of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. I had not considered the idea of martyrs ‘seeing’ before and found that very helpful. Thank you Keith, I hope to hear you preach again.

Thanks Keith, we always need people who see clearly and bear witness. It takes such courage. Or it’s easy to see something a long time ago and keep bearing witness to it, but forget to keep looking, to keep listening for the new song as well. We like the old familiar comfortable story (the partial truth) that we’ve gotten used to. And we don’t like getting publicly told off for something as big as unfaithfulness to God! Yes, it’s a dangerous thing to see clearly and bear witness. I wonder how we keep cultivating the capacity to hear uncomfortable truths about ourselves without shooting the messenger?

Thanks Keith. May we have the vision of heaven seen by martyrs.