A sermon on Revelation 7:9-17 & Matthew 5:1-12 by Nathan Nettleton

A video recording of the whole liturgy, including this sermon, is available here.

The Beatitudes, from the start of Jesus’s sermon on the mount in Matthew’s gospel, would have to rank as one of the best loved and most universally ignored passages in all of scripture.

We love them because we instinctively recognise them to be true and even strangely attractive. We ignore them, because actually living by them is unpopular and extremely costly. And when people do live by them, we dismiss them as fanatics. Once they have died and are no longer inconveniently proving us wrong about the impossibility of living by the beatitudes, then we dismiss them as saints.

The trouble with trying to live the beatitudes is that, from the normal perspective of our culture, they seem to add up to “blessed are the losers, blessed are the losers, blessed are the losers.” And yet we continue to find them strangely attractive. They continue to enchant us, to woo us, to whisper promises of another way, a way of freedom and lightness and joy. A way of life and hope.

Our reading from the apocalyptic Revelation to John shared some language and imagery with the visions of blessedness in the Beatitudes. The Revelation tells us of those who will be sheltered by God; who will never again hunger or thirst or be scorched by the heat of the sun; who will be led in safety by the great shepherd; and who will be guided to springs of cool clear water.

But in the Revelation, that vision is introduced as belonging to those who have washed their robes in the blood of the Lamb. The earlier description of this crowd depicts them as gathering around the Lamb, waving palm branches and shouting about salvation. It is an image that calls to mind the crowd greeting Jesus as he entered Jerusalem for the last time. We are reminded of how easy it is to shout in praise of Jesus, but how hard it is to stick with him when the chips are down.

As Jesus said on another occasion, “Not all who say ‘Lord, Lord’ will make it into the Kingdom.” Everyone wants to be alongside Jesus in the crowd waving palm branches when its exciting and fun. Not nearly so many want to be along side him when the crowd turns into a violent mob baying for his blood. When that happens, we are much more inclined to pull our heads in, deny we know him, and refrain from saying anything that might identify us with his agendas or with the losers who try to live by them.

Not this crowd though. These are the ones who have made it through the ultimate atrocity and have stayed faithful. These are the ones who have lived the struggle of the beatitudes. These are the ones who have washed their robes in the blood of the lamb.

It seems strange to us, something of a paradox, that those who are meek and merciful and pure of heart are so likely to be persecuted and martyred. Surely such people wouldn’t attract any animosity? But they do. They do, because living by such values is not actually an inoffensive stance.

It is often a matter of context. Sit here in church and talk of peacemaking and mercy and purity of heart and no one will bat an eyelid. But in the aftermath of the recent horrific Hamas terrorist attack when people is baying for vengeance and blood, standing firm for peacemaking is a risky thing.

When people are feeling angry about the release of a criminal, speaking of mercy will put you right in the firing line. When people flee from poor and war torn nations and seek asylum within our borders, no one wants to discuss what meekness would look like now. Try and live by the beatitudes, and people will take it as an offensive challenge to the way they live. They will say it is dangerous, un-Australian, or in the current climate even anti-Semitic. It has always been this way. That’s why Jesus was killed.

Again and again, Jesus refused to allow popular opinion and fashionable prejudice to determine the way he lived or the way he treated people. Again and again he refused to draw the lines where people said he should and kept welcoming those who popular opinion said he should shun.

While the conservatives and moralisers looked on, he partied with liberals and prostitutes and anarchists and gays. When the liberals and socialists started thinking he was one of them, he offered friendship to fundamentalists and right wing extremists and lynch mob ringleaders.

And the more he modelled this radical peacemaking, this purity of heart that refuses to define anybody as contemptible, the more he was hated and reviled and defined as contemptible himself. But he held his line and sure enough, his robes of righteousness and meekness were washed in his own blood, and yet even then, he continued to offer mercy. Even violence and death could not extinguish his passion for reconciliation. Even as the lamb who had been fatally wounded, he comes to us, without any bitterness or vengefulness, and offers us the confronting gift of pure mercy and love.

And in that offer of astonishing grace, we are confronted with the toughest decision we ever have to face. Will we accept that offer and commit ourselves to the struggle of the beatitudes that follows from it, or will we reject these beatitudes and this uniquely human embodiment of them, and throw our lot in with the winners who go on crucifying all those who suggest that there might be blessing in the way of the losers?

That is the question we are each challenged with in baptism. Will you walk in the ways of death, or make a break for freedom and be denounced as a fanatic and a loser and un-Australian? Will you put your trust in Jesus the Christ, and him alone? Christ alone. Not insurance policies, not defence forces, not the flag or the nation, not money and power.

Will you put your trust in Jesus the Christ, and him alone? And in practical terms, what does it mean to put your trust in Jesus the Christ? It means to commit yourself to living the life he asks of us, no matter how foolish it is regarded by the world around us, and to trust him to follow through on his promise that though we be poor and grieving and vulnerable and persecuted, that such a path will indeed be the most blessed of lives. To live otherwise is not to trust him at all.

That’s what we renew our commitment to every time we gather around the Lord’s Table and hold out our hands to receive the bread of brokenness, the bread of grief and mercy which feeds us and blesses us and sustains us for the struggle.

For at the baptismal pool and here at the Table we are awakened to a most wonderful promise, a promise that this feast speaks of and a promise that just might give us the glimpse of blessing we need for the living of such a life. For as we emerged from the baptismal waters, we did not arise alone to a life of isolated heroism. And as we stand at this table we do not stand and eat alone.

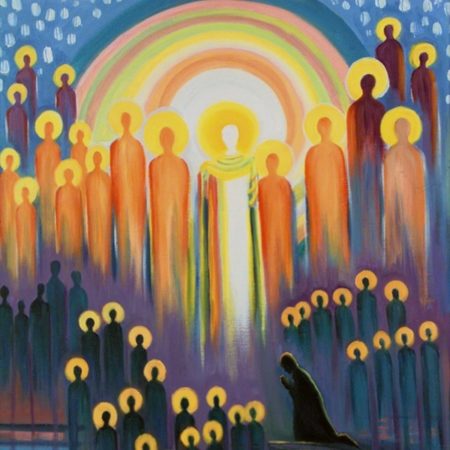

We emerged from the water to stand among a great multitude, who have come out of the great ordeal and have washed their robes and made them white in the blood of the Lamb. We gather around the table with a great multitude, from all tribes and peoples and languages, standing before the throne and before the Lamb, with palm branches in their hands, singing out in a loud voice, “Salvation belongs to our God who is seated on the throne, and to the Lamb! Holy! Holy! Holy Lord! Heaven and Earth are full of your glory!”

We are not in this alone, and if we were, we’d never make it. There is no such thing as a lone ranger Christian. We are baptised into the body of Christ, and it is in the body of Christ that we are raised to resurrection life and empowered to live the blessed life of the beatitudes.

That’s what this All Saints Day is about. In this celebration and in our regular celebrations of the Lord’s Table, we become conscious that we are living and praying in company. We gather here to read scripture and eat and drink and pray in the company of Mary Magdalene, and Francis of Assisi, and Joseph and Caroline Wilson, and Doug and Gladys Nichols. If we’re going to accept this gift of salvation and live the life that Jesus calls us to live, we’re going to be absolutely dependent not only on God but on these saints sitting around us, and not just on them but on all the saints who have sought to faithfully follow Jesus in various places down through the ages.

None of us have the courage to live the life of the beatitudes alone. And the tragedy of many of our churches is that we collude with one another to allow one another to choose not to live it together either.

But our God is extravagantly gracious and longs to see us set free from the tyranny of the ruthless and heartless way of the winners. Our God is extravagantly gracious and suffers even a tortured death to show us the pathway to resurrection life. Our God is extravagantly gracious and invites us again and again, no matter how many times we have denied him, to give up our collusion and delusion and to join hands with those who have been hated and persecuted and have washed their robes in the blood of the beatitudes; to join hands with them around the table, to eat and drink and dance as our prayers and praises unite with the prayers and praises of the whole communion of saints, across the world and across the ages, and with the whole creation in honour of the one God who holds us together in one body – the fullness of Christ who fills all in all.

0 Comments