A sermon on 1 Corinthians 15:12-20 & Luke 6:17-26 by Nathan Nettleton

A video recording of the whole liturgy, including this sermon, is available here.

Sometimes the more you dig into divisive religious disputes, the more you realise that both sides are just as wrong as each other. The reading about the importance of the resurrection that we heard from Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians is one that can quickly divide Christians into two hostile camps, both of whom are probably just as wrong as each other. The reading also shows that some of these disputes go way back.

The Apostle Paul tells us that there were people in the church back in his day who said that Jesus was not literally raised from the dead. Since it is clear that he’s talking about people inside the Church, it is not unreasonable to imagine that they might have been saying similar things to the many Christians today who teach that the resurrection was not a literal, physical, historical event. This view is frequently found among those who identify themselves as liberal Christians or progressive Christians.

There are many variations of opinion among them, but often it boils down to some variation of the idea that when the early Christians said “The Messiah was raised from the dead”, it was really just their way expressing ideas like “God’s project lives on!” or “Jesus lives on in my heart and mind,” or “I still see Jesus as my leader and teacher”, or even that “the risen Messiah is a metaphor for the Church empowered by the Holy Spirit”.

All of those ideas contain considerable truth, and I certainly have days when my faith in the resurrection struggles to go any further than that, but the Apostle Paul is pretty scathing about the usefulness of any teaching which seeks to reduce the resurrection of Jesus to something less than an unprecedented, earth-shattering, historical, physical event.

But on the other side of this debate nowadays is a group of Christians who often identify themselves as conservative or evangelical Christians, and who would gladly wave these words from Paul as a rallying flag, but who are probably misunderstanding it at least as badly in another direction. And for reasons I will try to explain a little later, that’s part of why they end up making enemies over things like this week’s failed religious discrimination legislation, or get themselves tangled up in things like the so-called freedom rallies.

Many would latch onto the line where Paul says, “If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins,” and weaponise it to attack the so-called liberals and progressives. “See, if you don’t believe in the resurrection, your faith is futile and your sins are not forgiven. Only we who believe in a literal resurrection are saved.” Which is actually nothing like what Paul is really saying.

It’s wrong because firstly it reduces faith to a kind of entrance exam, a bit like those horrific European language tests that used to be used by Australian Immigration Forces to keep out anybody they didn’t want under the White Australia policy. If you can’t pass the test we’re setting, you can’t come in. That is not the God made known to us in Jesus, and Paul does’t say that your sins are not forgiven if you don’t believe in the resurrection correctly; he says that you would still be in your sins if the resurrection hadn’t happened.

It’s wrong secondly because it misunderstands what Paul is saying about sin. Their view sees sins as specific violations of divine laws, which then need to be either punished or forgiven. But Paul here describes sin as something you are “in”, as in something that you are stuck in, entangled in, bogged down in. Sin is something that keeps us trapped and won’t let us be free.

And it’s wrong thirdly, and most importantly, because the combination of those mistaken views of faith and sin produce an understanding of salvation that, funnily enough, has no need of the resurrection. It ends up with this offensive image of a God who demands the sacrifice of innocent blood in exchange for pardoning our catalog of violations of God’s laws, which if true, would mean that our salvation was accomplished by Jesus’s death alone, and the resurrection would be nothing but an irrelevant miracle to impress us and try to get our attention.

But Paul doesn’t say that if the resurrection hadn’t happened, you might not have noticed that Jesus had already died for your sins. He says that if the resurrection hadn’t happened, you would still be in your sins. Period. The life, death, and resurrection of Jesus are all part of God’s project to break us free from the power of sin and corruption, but Paul is quite clear here that it is the resurrection that is the crucial move, and you wouldn’t know that from the preaching or singing of most of our conservative evangelical churches. Too many of us seem to think it is all about blood and death.

So let me try to unpack the experience of resurrection-centred salvation that Paul is pointing to and see what it means for us now.

Firstly, it is important to recognise that when Paul talks about salvation as being set free from sin, he is not talking about being set free from some future punishment for sins; he is talking about being set free from the power of sin to enslave us and ruin our lives here and now. If you are trapped in a locked house and, after you have given up searching for a way out and are lying on the floor in despair, someone unlocks the back door but doesn’t tell you, then your experience continues to be one of being trapped with no way out. Salvation though, is not being theoretically free; it is a lived experience of freedom.

I meant that as a simple illustration, but come to think of it, it actually isn’t far off the literal lived experience of the first Apostles. They were barricaded in a locked room, fearing for their lives when they first encountered the resurrected Jesus and experienced that encounter as salvation. Whatever had happened on the cross three days earlier had clearly not, on its own, set them free from the crippling power of sin and guilt and fear.

So how is it that encountering someone coming back from the dead was experienced by them as salvation, as liberation? Because, frankly, that’s not the way we normally imagine feeling about dead people rising, is it? Dead people coming back among us is something that happens all the time in the movies, but these are usually horror movies, and the appearance of the zombies, the risen dead, is a cause for terror, not hope and peace.

Now, that is not at all irrelevant to the significance of the resurrection of Jesus, because that normal fear and horror we would expect to feel if we encountered dead people rising is crucial to understanding what is so different about encountering the crucified Jesus rising up. It is the fact that in the encounter with Jesus it is immediately apparent that we are dealing with the exact opposite of such horror that explains why we experience encountering him as salvation; as forgiveness and liberation.

Two reasons. Number one. It is true that what Jesus and zombies have in common is that they are both experienced as simultaneously dead and alive. When Jesus appears in that locked room, which is spooky enough already, he shows the disciples that he still has fatal wounds. The book of Revelation tells us that even on the throne of heaven, Jesus appears to be a slaughtered lamb, both killed and alive, ruling in power. So what is it that makes Jesus so different from zombies?

The difference is which of those two states is definitive. The zombie is totally defined by death. In any zombie movie, people’s fear of zombies is like our common fear of death dialled up to eleven. Many people are terrified of touching a dead body, and zombies are like that fear amped up into terrifying reality. Death is pursuing us, grasping at us with its cold slimy hands.

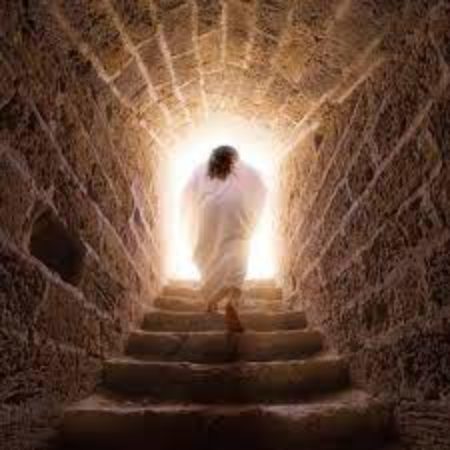

The risen Jesus is the exact opposite. The risen Jesus is totally defined by life. Yes, he is still the crucified one, and the scars of death are still apparent, but he reduces being dead to an utter irrelevance, and everything about him radiates joyous passionate life. Instead of his presence evoking in us the trepidation we feel about dead bodies, it evokes in us the wonder we feel in the presence of a beautifully perfect newborn baby. Everything about him says “wondrous miracle of life!”

That was difference number one. Now number two.

The fear of the dead coming back is also a fear of the ultimate vengeance. Zombies are terrifying because they hold us responsible for their violent deaths, and they have come back to get even, to take vengeance, and we can’t stop them by killing them, because they have already been killed but they keep coming back. So the encounter with the living dead is like the ultimate in your past catching up with you.

So let’s imagine ourselves now being among those original disciples. Three days ago Jesus was violently lynched and murdered, and we denied him and abandoned him. Or maybe we were just there in the crowd of people who were chanting “Crucify him. Crucify him.” If he were to come back as a zombie, we have every reason to be afraid.

But the encounter with the risen Jesus is experienced as salvation, forgiveness and liberation, precisely because it is the exact opposite of that. The one who has every reason to want to get even with us, to want vengeance, is encountered instead as the absolute embodiment of love and forgiveness and warm acceptance. He doesn’t even need to say, “I forgive you”, because everything about him makes it abundantly obvious that not the slightest thing is being held against you. There is not the least hint of a grudge or a resentment. He doesn’t even seem disappointed in you. Just overjoyed to see you, to embrace you, to speak words of love and peace and freedom to you.

This is not some bewildering theory of transactional salvation. This is not something you have to try to understand and believe for an entrance test somewhere. This is wholly and solely an experience of being forgiven and set free. You just have to welcome it, and how could you not?

Well, to be honest, there probably is an answer to “how could you not?”, and indeed there are plenty of people who don’t. And it probably boils down to the fact that when you encounter something as shocking as resurrection, something that upends everything you thought you knew about everything, it can be quite painful to let go of some of the things that we thought we knew, some of the things we had built our worldview around. This is where we get back to things like religious discrimination legislation and freedom rallies.

The resurrection reveals all sorts of things, including lots of uncomfortable truths, and one of them is what the death of Jesus actually meant. Rather than revealing that God demands blood sacrifices and that punishing evil-doers is something we do on the authority of God, the crucifixion of Jesus reveals that sacrificing innocent victims is something humans do when they are still mired in sin and unable to escape. It reveals that humans are so addicted to identifying one another as good and evil, and so incompetent at doing it, that they will actually crucify God, given the chance. Rather than God authorising our systems of judgement and punishment, God is the archetypal victim of those systems.

When the risen Jesus causes the scales to fall from our eyes, we see that all the beliefs that we used to convince ourselves that we were the good people, favoured by God, are part of the sin that ensnares us. This is the web of pride and hostility and fear and resentment and paranoia that confines us and cripples us and chains us up. This is the entanglement that sees us waving flags in the street and chanting for freedom, while obviously handing over control of our hearts and lives to mob anger and vengefulness, and in the name of freedom, fuelling the very resentments that enslave us.

This is the entanglement that makes us imagine that we are being persecuted by evil people when all that is happening is that they are seeing us as a mildly amusing irrelevance. It makes us imagine that we need legislation to protect our rights when all that is happening is that people are laughing at us for believing in an imaginary friend or being followers of the friendly zombie, when all we really need is to get over our resentment at the loss of our past privileges.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not opposed to amending our anti-discrimination legislation to ensure that people of various faiths are not denied proper access to all our society offers. But I am against us Christians pretending we are being persecuted just because people laugh at us and no longer assume that we automatically get the last word on morality.

You might have noticed that in the beatitudes that we heard from Jesus in our gospel reading, when Jesus said “Blessed are you when people hate you, and when they exclude you, revile you, and defame you on account of the Son of Man,” he did not go on to say “Legislate against them to make sure they can never do that to you again.” He said, “Rejoice in that day and leap for joy, for surely your reward is great in heaven; for that is what their ancestors did to the prophets.”

When we encounter the risen Jesus, we encounter one who is defined entirely by love and life, and who sees our petty grievances and our addictions to trying to force our will on others as mere barnacles of an old life to be brushed off and left behind as we follow him into the wide open spaces of love and life.

When we encounter the risen Jesus, we can suddenly see that his teachings such as the beatitudes, far from being another legal code to be used for dividing up us and them and justifying our fierce opposition to “them”, are actually an invitation to side with Jesus as he takes the side of every victimised “them”, and there to find the life that is truly life.

When we encounter the risen Jesus, we see that our fears of losing freedoms or privileges, and our flag-waving anger towards every other “them”, has never ever been a part of who God is or how God approaches our world, and we see, in Jesus, the pathway out of their befouling entanglement.

When we encounter the risen Jesus, we discover that everything is about life, and that even the prospect of being dead becomes an utter irrelevance as those wounded hands reach out to us and embrace us in the cosmic hug of unbounded love and unquenchable life.

And when that happens, Paul’s if-Christ-has-not-been-raised question hardly bears thinking about.

One Comment

Thank you, Nathan. One of the top picks of a very good bunch.