A sermon on Galatians 4: 4-7 by Nathan Nettleton

A video recording of the whole service, including this sermon, is available here.

At Christmas you often hear people say things like, “It’s a pity that in all the rush we don’t have time to think about what Christmas really means.” Well, if you are one of the people who was thinking that, there is good news.

The Christian Church actually celebrates the Christmas season at a different time to the summer festivities that go by the same name. We in the Church begin our celebration on the day when everyone else finishes theirs, and so after the Feast of the Nativity, or Christmas day, we have a further eleven days to reflect upon and celebrate what the incarnation of Jesus means, and we are no longer being bombarded by images of reindeer, Santa Claus and shopping day countdowns. This is our time, in one of the quietest times of the year, to think about what it means to us and to our world that Jesus was born as one of us.

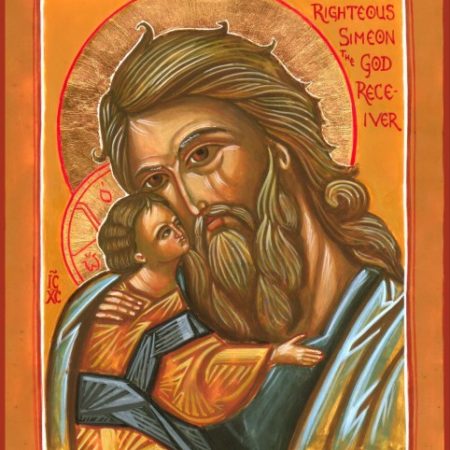

Paul’s letter to the Galatians is not a part of the Bible that the popular imagination usually associates with the Christmas season, but if you want a brief potted summary of its message, the few verses we heard read from it before are probably about as good as you could ever hope to find. Perhaps a look at them will help us to get beyond the tendency to think of this as nothing more than a twelve day birthday party for cute little baby Jesus.

These verses reflect on the nature of the incarnation, and give us some insights into both what it meant for God, and what it means for us. I’d better pause for a definition in case some of you are not familiar with this theological jargon word: ‘incarnation’. You will hear me use two versions of it: incarnate and incarnation. It refers to the act of becoming present in a body, or becoming a person with a body. You will occasionally hear others use it of people, especially if they believe in reincarnation (re-incarnation). They will speak of someone who used to be incarnate in another body in a previous life, finding a new incarnation; that is becoming present in a new body.

So when we speak of the incarnation of God in Jesus, or of God becoming incarnate in Jesus, we are talking about God becoming present among us in bodily form as a human being named Jesus. We imply that God can and does exist without a body, as Spirit, in a form that we cannot touch or see; but we are saying that in Jesus, God has become completely present in a human body, in a form that is not only touchable and seeable but which is subject to all the limitations and vulnerabilities that we, as incarnate people, are subject to.

This is precisely what is described in the first verse we heard from Paul:

When the fullness of time had come, God sent his Son, born of a woman, born under the law.

Even before we begin to think about why God might have done this, or what impact it might have on us, this is an extraordinary claim. The biggest miracle of the Christmas stories is not that a virgin became pregnant, but that God became incarnate. Actually, with today’s technology, a virgin becoming pregnant need not be a miracle at all. It would require nothing more than a simple little medical procedure — they do it with cows and sheep all the time. But God becoming incarnate is analogous to the medical practitioner not just impregnating the virgin, but turning himself into an unborn baby and placing himself in her womb, and wagering his whole future on the hope that she won’t miscarry him.

When God becomes a human being — becomes incarnate — God is voluntarily exposed to the same fears and risks and dangers that the rest of us face. In birth, God is exposed to the risks of a fatal complication. In childhood, God is exposed to the risks of childhood accidents, or growing up in poverty, or child abuse.

Throughout an incarnate life, God is exposed to the threat of violence, to the humiliation of living under the heel of hostile forces, to the fear of terrorist attack or a global pandemic.

Throughout a human life in relationship with other human beings, God is exposed to the risks of being misunderstood, of being rejected, of being betrayed, of being falsely accused and eliminated. When God becomes one of us, God cops life in all its beauty and ugliness, just like we do.

Now that is utterly amazing in itself. But the next question is “why?” Paul addresses the question in his next verse, and then elaborates on it in the rest of the passage. He says that God sent the Son into such circumstances so that he could get everyone else out of them. And then in elaborating, he puts it in family terms. The Son did what he did in order that we might have the opportunity to be adopted into God’s family.

What we have here is the most extraordinary exchange of gifts. We give Jesus our humanity, and he accepts it and offers us his divinity in exchange. He becomes a child of human beings, in order that we might become children of God. He becomes what we are, in order that we might become what he has always been. Paul is quite explicit about this. Because you are now God’s children, the Spirit of God’s child — Jesus — has been sent into your hearts.

And, he says, this changes everything because as God’s children, you are no longer at the beck and call of the things that once dictated your every move. We no longer have to go with the flow and slavishly do whatever the world around us prescribes for us to do. We no longer have to become paranoid and isolationist when the society around us talks up the fear of the outsider. We no longer have to compulsively consume when the society around us tells us that our worth is measured by the sexiness and up-to-the-minuteness of our accessories. We no longer have to destroy ourselves and our loved ones by trying to conform to the impossible images of youth, beauty and success that are constantly bombarding us. It is different now, because we have become children of God, and as God’s children we will receive from God all that has been kept in trust for God’s children.

Jesus was born under the thumb of those pressures and constraints, just the same as we are. But he came into such a life to enable us to find a way out. When God became incarnate in Jesus, he put himself in our hands, at our mercy, so that we could put ourselves into God’s hands and receive God’s mercy. And at the table we will come to shortly, Jesus continues to put his body into our hands, so that we might continue to put ourselves in his hands and know ourselves as God’s beloved children.

One Comment

As I reflected on this sermon – I remembered an image I saw many years ago during the Victorian Carols by Candlelight – the Carol – “Hark the Herald Angels” – was being sung and in the second verse there are these lines – “Veiled in flesh the Godhead see, Hail the incarnate Deity, Please as man with man to dwell, Jesus our Immanuel ” – as we sung these words the camera person slowly brought the camera focus down on a very tiny baby asleep in his mother’s arms and I wondered at the insight of this person to imprint on my mind forever this image of an unknown baby sleeping – “Veiled in flesh the Godhead see” and the question in my mind “Was it an accident?” or “Did they truely understand?” – either way “I got” it

as I got the sermon.