A sermon on Romans 6:3-11 for the Paschal Vigil by Nathan Nettleton

Jesus is risen from the dead, and everything is changed. Jesus is risen from the dead, and we begin to see that we were wrong about nearly everything we thought we knew. And what a joy it is to know that we were wrong! Often it is just embarrassing to discover you’ve been wrong, but not this time. This time it is the best news ever.

We thought death was the only sure and certain thing in life, but we were wrong. Irrepressible life turns out to be far more sure and certain than death. We thought that sin was something we had to work really really hard, with gritted teeth and sweating brow, to overcome by rigid and joyless discipline. Freedom from sin turns out to be a wide open garden of love that we are invited to relax in.

In fact, we thought we knew what Jesus was talking about when he spoke of people being trapped in a life of sin and death, but it turns out we had almost no idea at all. We were so wrong. And thank God we were! We were so wrong, and that’s the best news ever, because the truth that we beginning to see when we encounter the crucified and risen Jesus is so much better, way way better than we could ever have imaged.

One of my favourite theologians, James Alison, recognised this wonderful paradoxical good news in the title of one of his books: The Joy of Being Wrong. The Apostle Paul might have used a somewhat similar title for the words we heard from him tonight (Romans 6: 3-11), but you can hear something of his frustration too.

The trouble with us ordinary human beings is that our first instinct when we discover we have been wrong is to cling even more tenaciously to our errors. Our minds defend themselves furiously against the onslaught of contrary realisations. We deny them or qualify them or compartmentalise them into some realm where they can’t touch the core of our lives.

“Jesus is risen, so everything we thought we knew about death and sin and life and religion appears to have been wrong.”

Well, our sophisticated rational minds reply, that’s an attractive and harmless myth that speaks of the way that no one is really dead if their memory lives on in the loved ones they’ve left behind. And even if there is something a bit more to it in the case of Jesus, well that’s because he was special and unique and it was a long time ago. It’s not really relevant to our daily lives. But if you really want to make a big deal out of it, that’s okay. We have a nice harmless religion for you, and we might even be able to get them to stop the football for a day while you say some harmless prayers and enjoy your hot cross buns and chocolate eggs. We weren’t really wrong, were we? Not about anything that really matters anyway, were we? Not about anything life-changing?

Oh yes, we were! But don’t we struggle to see it? Do you hear the Apostle’s frustration? “Do you not know?” he pleads. “Are you still not getting your heads around this?” “Do you not know that all of us who have been baptised into Christ Jesus were baptised into his death? And if we have been united with him in a death like his, we will certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his.”

Are you still not getting your heads around this? Just how different this is? Maybe it is no wonder. Unlike the first apostles, we haven’t had the earth-shattering experience of seeing someone tortured to death, and knowing all our hopes and dreams completely extinguished with him, and then three days later encountering him bursting with life and love and joy and calling us to follow him on the road of life again.

Perhaps for us it is always going to be harder to get our heads around just what it all means. It is one thing to know it as an old religious story. It is quite another to know it as a life-changing and world-transforming force blowing powerfully through everything we have ever known or thought we had known.

Part of our problem of comprehending the resurrection of Jesus and its implications is that part of what it reveals is that the ultimate truth is only arrived at by interpreting it backwards, and we are thoroughly accustomed to doing our thinking forwards in logical chronological sequences.

So, when we want to try to make sense of resurrection, we begin by thinking about death and what we know of what death means, and then we try to proceed forward to what resurrection might be. And when we do that, we literally run into a dead end. It just doesn’t compute.

Similarly, when we want to try to understand the forgiveness of sins, we try to begin with an analysis of our sinfulness. We think we know what that is: its all those bad things we do. We imagine that God has a list of them, and forgiveness is when God looks at the list, frowns, looks over his glasses at us with obvious disappointment, and then offers us one more chance. Somehow we end up with a not terribly encouraging picture of forgiveness.

But the truth is that the resurrection is never going to fit into our usual chronological methods of making sense of our lives and our world. By definition, the resurrection is something that breaks all the rules and turns everything upside down and back to front and inside out. It even makes a nonsense of the process of trying to think about it!

Let me borrow an illustration from James Alison to see if I can help you see what this means. Perhaps you have heard of the phenomena of prisoners becoming institutionalised in jail. They become so accustomed to the ways things work in the jail that they are no longer able to cope if they are suddenly released into the outside world. Now come on a little imaginative exercise with me.

Imagine that rather than being an ordinary prisoner who can at least remember life outside, you are the child of life-sentence prisoner, and you have been born and raised in the prison. And the authorities and the other prisoners have conspired with your mum to protect you from ever hearing of the world outside. They think that little you will cope better with your life growing up in the prison if you believe that it is normal and that there is no other world outside the prison. This is all there is. Get used to it. And so you do. And years later, you have grown to adulthood, and still you know nothing of any world other than your little perfectly normal imprisoned world.

One day some preacher comes along saying something crazy and unimaginable. “Do you not know that we who were imprisoned with Jesus have now been set free with him? If we were condemned to prison with him, we will certainly be united with him in his liberation.” It would make no sense at all, would it? You simply have no frame of reference with which to make any meaning out of such a statement. What could “being set free” possibly mean, since you have no idea that you are imprisoned? This is all there is, isn’t it?

But now, let’s imagine that someone – let’s call him Jesus – comes into your prison and calls you by name and says, “Follow me”, and you do, and he leads right out the door and into a whole new world that you had never even known existed. Now, if he led you out and then left you to your own devices, you’d be terrified and you’d turn around and flee straight back to your familiar world, just as the Israelites kept wanting to do when Moses led them out of the land of slavery.

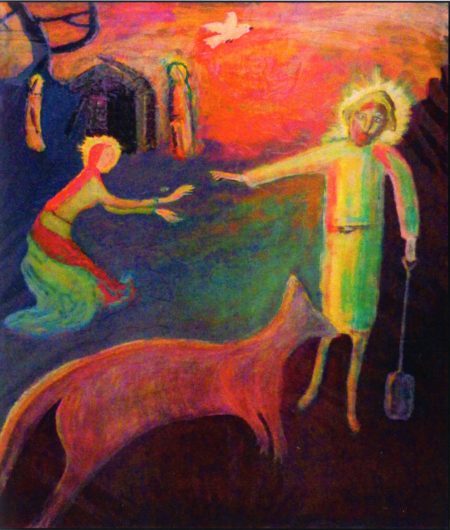

But this Jesus doesn’t abandon you. He takes you by the hand and gently and joyously leads you step by step into a whole new wonderful life, a life of previously unimaginable liberty and fun and joy and love and colour and, well, life, life in all its fullness.

Now stop and think about how you would then interpret the story of your past life and the meaning of your life from here on. You were completely unable to understand freedom from inside the prison, but actually, you were unable to understand the prison either. You could live in it and cope with it, but that was precisely because you didn’t really understand it. But now you can understand it. You can understand it by looking backwards from the place of wondrous freedom you now live in. The old life can only be properly seen for what it really was after you have begun to enjoy the new life of freedom. And the more fully you begin to live the new life, the more fully you will comprehend what a stunted and sad life you had in the past.

The resurrection life we share with Jesus is a lot like that. It makes no sense at all so long as we are still living in the prison of normal human culture. The apostles can call it the life of sin and death all they like, but so long as it is the only life we know, they are not going to get us to change. There is nothing else. Just get used to it. And we have.

But when Jesus rolls aside the stone and beckons us to follow him, it is the promised land of life and love outside that enables us, for the first time, to comprehend why a life of sin and death was called that. Sin turns out not really to be little actions that God frowns disapprovingly at. We got that all wrong. Sin turns out to be the whole of life as it is lived when we are institutionalised to a world devoid of freedom and love and mercy.

So, once we have been welcomed into the promised land of mercy, we can begin to see how wrong we were and how stunted our life of sin and death was. We only really know what sin is when we see it in the rear view mirror as something we are leaving behind. We only really know what death is when we see it in the rear view mirror as something we are rising from and dancing joyously away from.

And, of course, the implications of this dance off in all directions, but tonight is not really about trying to analyse or explain them. It is about celebrating them, welcoming them, and surrendering ourselves to them. It is about taking little more than a parting glance over our shoulders at that miserable stunted old life, as we join our crucified and risen liberator in the joyous dance of life and love and freedom and earth-shattering, prison-breaking, mind-boggling mercy and joy.

Look back there. We were wrong! About everything! Thanks be to God!

0 Comments